How to Teach a Long Novel

How to Teach a Long Novel:

Keeping Readers Involved & Engaged

No matter whether you love or loathe the long novel you teach, the same struggles pop up every time we come around to teaching it year after year. For me, it’s To Kill a Mockingbird. It’s a 400 page monster! It’s fun dawdling around with setting and making maps of Maycomb and then rolling through Boo Radley anecdotes., but before we know it, August has turned into December. I’m kidding, of course, but time truly does have a way of slipping away as we work through a long text. And there’s nothing worse for kids than dragging out a book for too long! Here are my best suggestions for getting through your version of my Mockingbird.

Start with a killer Essential Question

An Essential Question is the cornerstone of a great unit, no matter how long the novel is, but when working with a long text, having an essential question helps serves as an anchor point that keeps everyone focused. Leading into your novel with an essential question helps answer the question “Why are we reading this book?” and helps you decide which lessons to teach and which to leave out. For more ideas that will help you get started with writing Essential Questions, check out this blog post!

Consider teaching PARTS rather than CHAPTERS

For a long tie, English teachers have subscribed to the instructional method of assigning chapters for homework followed by reading quizzes. This is pretty much (with some variation) what I do with The Great Gatsby, but it’s only nine chapters long! Assigning chapter by chapter reading in a book with 20+ chapters, to me, seems to make the reading already feel like a chore. Consider this: break the reading up into larger parts and give students more time to read. These parts might already exist in the novel or you can make them based on the page numbers that need to get covered. Now, students are reading Part One over a 1-2 week period, giving you a larger territory to use for bigger picture, thematic lessons, and students have more autonomy about where and when they get their reading accomplished.

This method often makes teachers panic. Here are a few of the concerns I always hear:

What if the student’s don’t read? Well, the truth is, students probably weren’t going to read your nightly assigned chapters, either, so we have to think about solving that problem in other ways. Why not give them the sense of independence by only having three “assignments” due rather than fifteen?

Won’t it be too hard if I don’t check in more often? Use your best judgement because, yes, this might be the case. There are a lot of texts, however, that benefit from understanding the big picture rather than zooming in on every single detail. Mockingbird is a perfect example of this. I’m really not concerned with students having a perfectly accurate read for every single chapter or every single character. What’s really important to me is getting to the point in the novel where we can start to have really serious conversations about justice, privilege, and symbolism. If we stop to examine every prank the kids pull on Boo, we’ll never get there. By grouping those chapters all together, we’re likely to come together as a class at the end of the allotted time for reading and hit the major ideas.

Won’t they forget about specific details? Think about the first time YOU read a book. Did you catch all of the details that you’re so desperately holding on to for your students right now? Probably not! We need to give ourselves permission to not feel the burden of “covering” every single magnificent literary moment in a text. Stick to the details that illuminate your essential question and if some of your favorite lines or moments get glossed over, IT’S OKAY! Remember, we’re teaching teenagers with shortened attention spans. We need to pick the best of the best, get in and get out! Just keep swimming...

Casually check in with reading progress using Google Forms/Classroom

Especially when I give a lengthier chunk of text for students to read, I like to send them a quick little (ungraded!) check in. I simply create a Google Form that asks students things like this:

About how much of the reading have you completed? (0%; 25%; 50%; 75%; I’m done!)

What points of confusion have you found so far?

How can I help make the reading more clear for you? More enjoyable?

Which character do you like the best so far? Why is that?

Are you liking the book so far? Why or why not?

Questions like this are sneaky :-) Students who are really reading will voice their concerns and give you solid answers and you’ll get great insight into a students’ reading experience. On the other hand, students who are not reading or are struggling with the reading will reveal that pretty clearly, too. This gives you a chance to pull a student aside individually and talk to them about what’s hindering their reading progress. You’ll be able to catch issues before your reading quiz or before the due date for the assigned reading.

Set up a reading calendar...and stick to it!

I know this sounds basic, but it’s the best way to keep your pacing on track. Make your calendar, print it, hand it out to students, and post it on Google Classroom. Your close reading lessons could also be included here, helping to establish a practice and develop a routine. This calendar commits you to finishing each piece of the novel on the timeline you established in your initial planning. Sure, you can always make adjustments if you have to, but for the most part, having the calendar will force you to keep moving. I’m the first to want to extend a chapter after I had a great idea in the shower the night before, but then my units turn into twelve week long nightmares! Make your calendar and stick to it.

Offer multiple types of assessment formats

If you want to keep the energy moving, assess the students with some variety. Here are a few things that I like to incorporate:

Two Truths and a Lie: Just like it sounds - give the students two true statements about the reading paired with a lie and let the discussions begin! It seems very elementary on the surface, but once students start debating, be prepared for some really thoughtful discussion.

Door Quizzes: I like to throw “pop” door quizzes every now and then. In this type of quiz, students are stopped at the door with a quick and easy comprehension level question and students cannot enter the door until they can answer the question . If they get an answer incorrect, they stay in the hallway, take out their books, and reread until they can figure out the answer! Students who get the answer correct are allowed to enter the classroom. Once inside

FlipGrid: Simple questions about character and plot take on a whole new energy when they’re answered on FlipGrid. Ask the easy questions or do something more adventurous like putting students into small groups or pairs to reenact a scene!

Socratic Seminars: circle up the desks and let’s get talking! Socratic seminars come in many shapes and sizes, but here’s why they’re great for long novels: big picture questions can be answered from so many different places in the novel. With shorter texts, sometimes students repeat similar examples to answer questions, but with a longer novel, students have more to draw from. Bonus? Grade on the spot as students are talking - no take-home work for you!

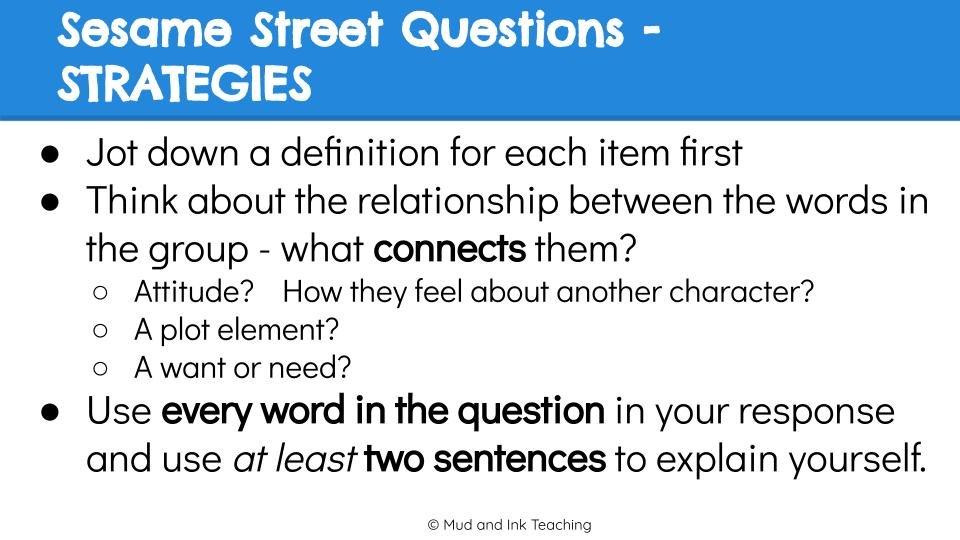

Sesame Street Quizzes: They’re by far and away my favorite type of quiz. Listen to the Brave New Teaching podcast episode that walks you through them and share your info below and I’ll send over my quiz template and practice lesson!

Stagger the unit with high interest non-fiction, poetry, and visual text

I know this sounds contradictory: add more reading to the unit with the longest book. While that’s true, we know that we also need to keep our texts relevant. Clips from movies with strong connections, news articles from around the world, and poetry that speaks to the experience of a character all make for a more enjoyable reading experience and help build connections for kids as they read. Also, these text might be the ONLY text that are read by certain students. Remember those kids we talked about earlier? The ones you’re worried won’t read the book? They might not be reading as much as you hope, but they WILL close read a poem with you in class. They WILL talk about the article that you put in front of them that makes a connection. Sometimes, these little moments inspire kids to want to know what they’re missing in the novel and offer important big picture considerations that might be missed otherwise. With To Kill a Mockingbird, I love to show the documentary 13th from Netflix and read about the wrongful imprisonment of Kalief Browder.

Hopefully, these ideas can make teaching your long novel a joyful skip through a field of wildflowers instead of trudging through the 8th circle of hell. Trust me, I’ve been there! What are the long novels that you teach? What struggles to you face? What strategies have you tried that have worked well for you? Let us know in the comments below!