ADVENTUROUS TEACHING STARTS HERE.

Cultivating Critical Thinkers: My Approach to Teaching Literature

As an educator, I've always been passionate about instilling critical thinking skills in my students. It's a topic that I recently had the opportunity to reflect on during a professional development session, and I want to share with you the insights and strategies that I believe are essential for deep engagement in the classroom.

Cultivating Critical Thinkers: My Approach to Teaching Literature

As an educator, I've always been passionate about instilling critical thinking skills in my students. It's a topic that I recently had the opportunity to reflect on during a professional development session, and I want to share with you the insights and strategies that I believe are essential for deep engagement in the classroom.

Challenging the Status Quo

During a recent PD session, I found myself in a bit of a controversial spot. I questioned a fellow teacher's approach to curriculum, which led to a broader discussion about our roles as educators. It's crucial for us to think like our students and to prioritize deep critical thinking over simply entertaining them. We need to focus on developing skills that lead to deeper critical thinking and provide opportunities for students to engage authentically with the material.

Teaching Literature Beyond Comprehension

When it comes to teaching literature, my approach might be a little unconventional. I steer clear of recall-based or plot-based activities. Instead, I encourage students to seek out summaries on their own and focus on the bigger issues at hand. It's about letting go of the minor details and teaching students to read for big picture connections. Comprehension is important, but it shouldn't be the primary focus. We should be guiding our students to think critically about broader themes and societal issues.

The Power of Close Reading

Close reading is a significant part of my teaching strategy. It's not about getting through an entire novel; it's about diving deep into passages and analyzing them. This mirrors adult book club discussions where despite different levels of recall, everyone can contribute meaningfully to the conversation. Close reading fosters a collective understanding of the text and teaches students valuable rhetorical and literary analysis skills.

Pairing Texts and Media for Enhanced Engagement

I'm a big advocate for pairing contrasting texts and media to stimulate critical thinking. For instance, combining literature with podcasts or other media that address relevant societal issues can create a dynamic learning environment. This approach encourages students to engage critically with the material and see the connections between the text and the world around them.

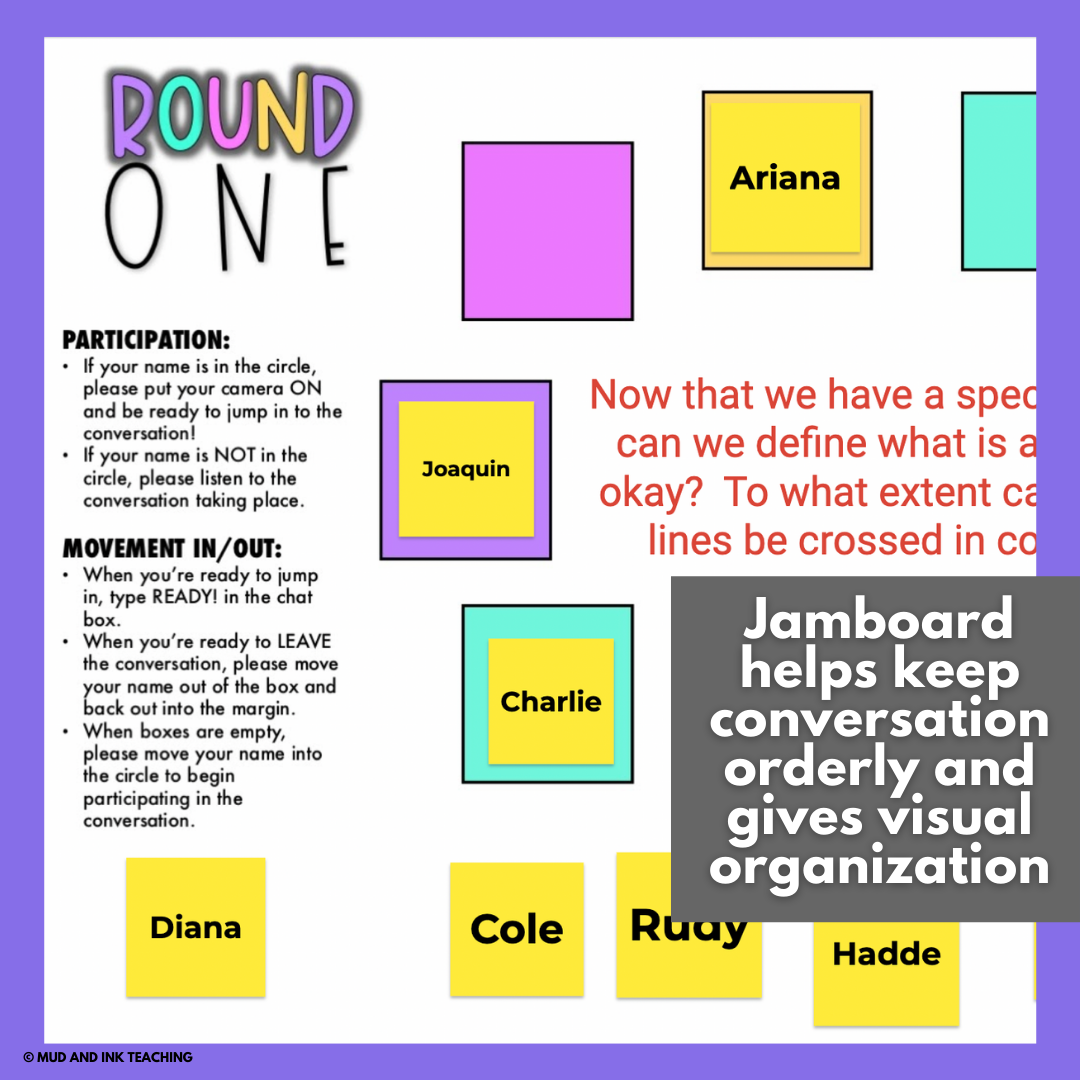

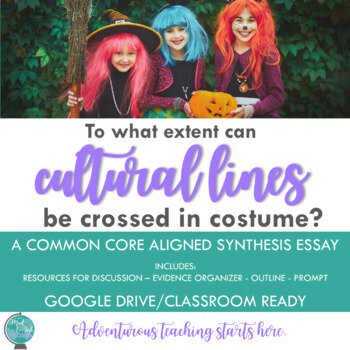

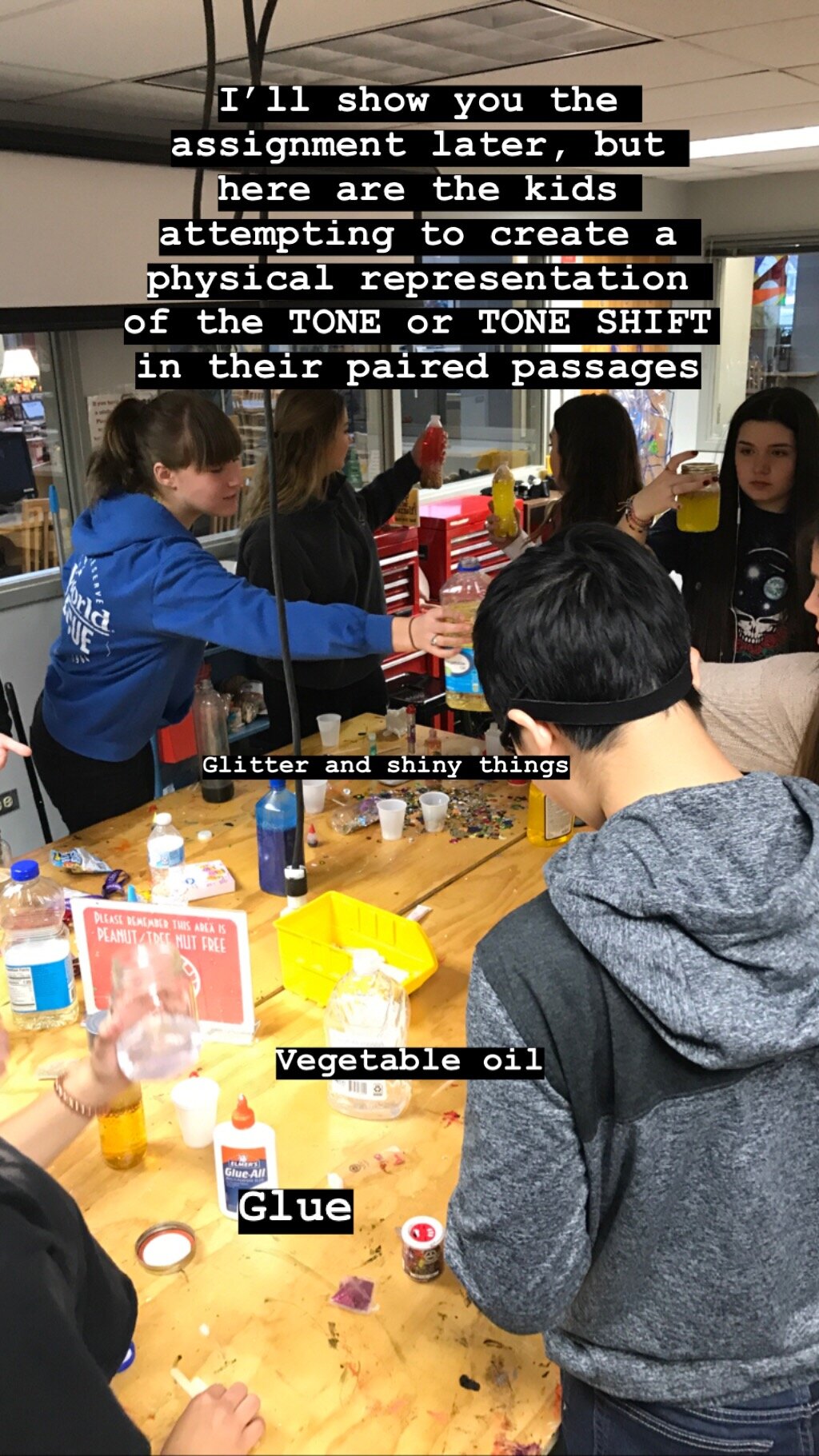

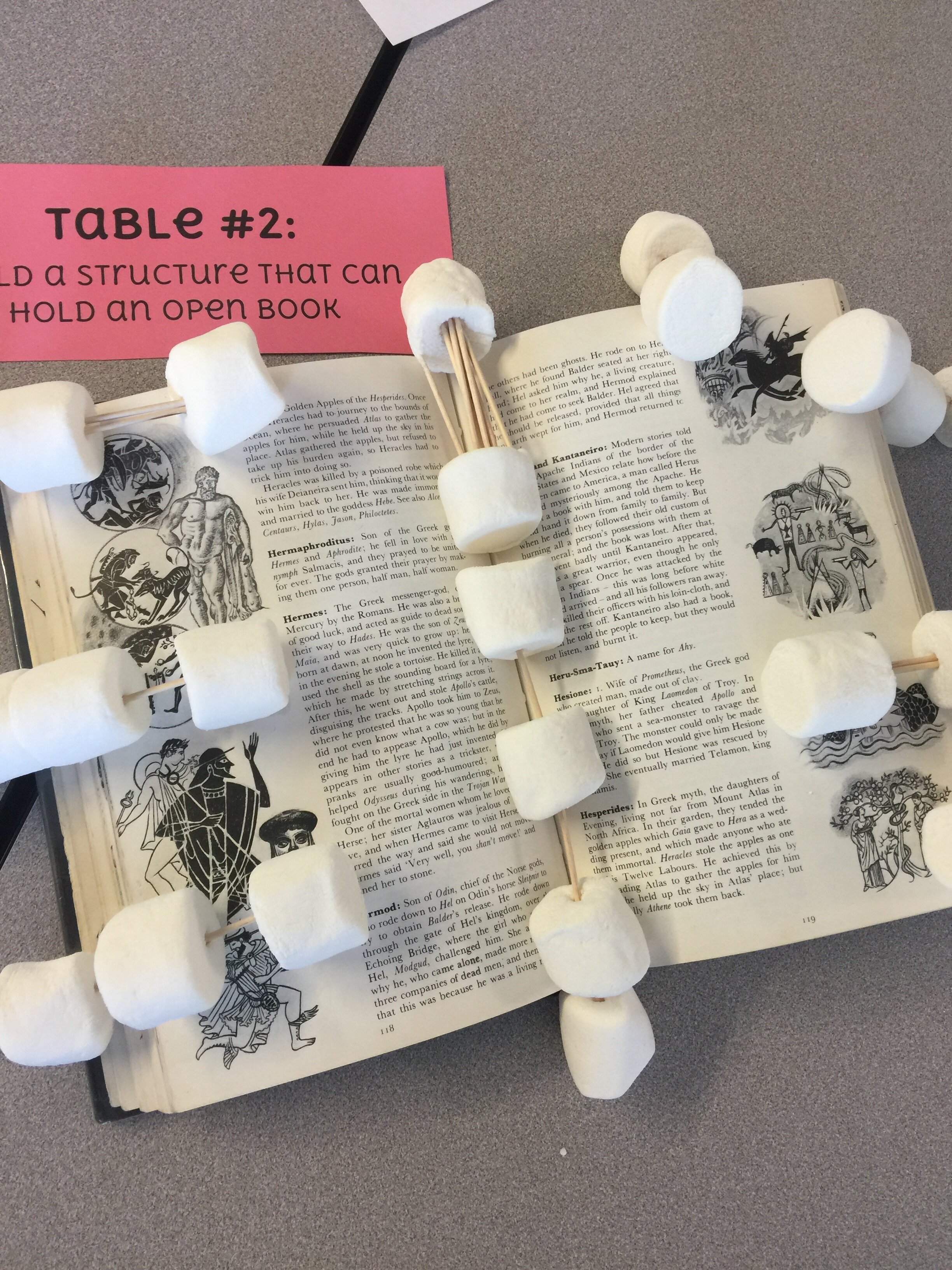

Visuals and Hands-On Activities

Incorporating visuals and hands-on activities is another way to enhance metaphorical thinking and create moments for critical thinking in the classroom. These methods help students to visualize and interact with the concepts in a tangible way, further deepening their understanding and engagement.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Deep Engagement

My approach to teaching literature and critical thinking is all about prioritizing deep engagement, critical analysis, and real-world connections. It's about cultivating students' ability to think critically about the world around them. As educators, we have the power to shape how our students perceive and interact with the world, and it's our responsibility to equip them with the skills they need to navigate it thoughtfully and analytically.

In the end, the goal is not just to teach literature but to foster a generation of thinkers who can analyze, question, and contribute to society in meaningful ways.

READY TO TRY TEACHING EQ DRIVEN UNITS?

LET’S GO SHOPPING

Planning a Novel Unit Reading Calendar

The art of pacing out the reading during a novel unit can be tricky, so we’re going to take some time today to talk through the process. Whether you’re teaching a classic or a contemporary YA title, there are special considerations to be made for the design of your calendar and how we backwards plan for ELA. Let’s jump in!

Planning a Novel Unit Reading Calendar

The art of pacing out the reading during a novel unit can be tricky, so we’re going to take some time today to talk through the process. Whether you’re teaching a classic or a contemporary YA title, there are special considerations to be made for the design of your calendar and how we backwards plan for ELA. Let’s jump in!

For a while now, I've had the pleasure of guiding countless teachers through the intricacies of curriculum design and instructional coaching. In one of our most recent videos, I delved into a topic that's crucial for any literature teacher: creating an effective reading calendar. Today, I want to share with you the insights and strategies I discussed for building a reading calendar specifically tailored to the novel Fahrenheit 451. You can skim through this post to see the gist and then watch the full video when you’re ready!

Understanding Your Timeframe

The first step in crafting a reading calendar is to get a clear picture of the real time you have available for the unit. It's not just about the number of days on the calendar; it's about the actual class time you can dedicate to reading, discussions, and assessments. This understanding is foundational because it shapes how you'll pace the novel and plan your activities.

Setting Clear Assessment Goals

Before you dive into the reading schedule, it's essential to set your assessment goals. What do you want your students to achieve by the end of the unit? How will you measure their understanding and engagement with the text? These goals will guide you in structuring your calendar and ensuring that each activity aligns with your objectives.

Structuring for Engagement and Ownership

A well-structured reading calendar does more than just outline what to read and when; it fosters student ownership and engagement with the text. I advocate for backward planning, which means starting with your end goals and working backward to determine the steps needed to get there. This approach ensures that every part of your calendar is purposeful and directed towards your learning outcomes.

Decentering the Text for Broader Discussions

In our discussion, I emphasized the importance of decentering the text to allow for broader analysis and discussions. This means assigning larger chunks of reading at a time and not getting bogged down by focusing solely on the text itself, and instead, focusing on the essential question. By doing so, you create space for students to connect the novel to larger themes and ideas, which enriches their learning experience.

A Week in the Life of a Reading Calendar

PIN ME!

Let me give you a glimpse into how I structure a reading calendar. Mondays are for assigning reading, which sets the tone for the week. Tuesdays are reserved for small group activities, which encourage collaboration and deeper understanding. Wednesdays and Thursdays are perfect for close reading exercises, allowing students to dive into the text's nuances. This structure balances guidance with autonomy, giving students the framework they need while empowering them to take charge of their reading.

Flexibility and Adaptation

One of the most important lessons I've learned is the value of flexibility. Every classroom is different, and what works for one may not work for another. It's okay to adjust the reading schedule based on your school's timetable and to be open to rearranging assessment, small group, and close reading days as needed.

Final Thoughts

Creating a reading calendar for Fahrenheit 451 or any novel is a balancing act between structure and flexibility. It requires an understanding of your timeframe, clear assessment goals, and a willingness to adapt to your students' needs. I encourage you to use the template I've provided as a starting point and to check the description box for additional resources.

I wish you all the best in planning your reading calendar. Happy teaching!

LET’S GO SHOPPING

Does Taylor Swift have a place in the ELA Classroom?

And here's the thing: if your students are talking about Taylor, then so should you. This is an open door into engagement and skill building that is not to be missed. Here are three ways to pull the power of Taylor into your classroom and spike engagement among your students…

Well, let's get this out in the open: I'm NOT a Swiftie. I hope we can still be friends, but Tay Tay doesn't have a hold on me in pure Swiftie fashion. To be clear, I'm also not a hater. I'd call myself “Taylor-Neutral”.

Whether you are a die-hard fan or completely out of the scope of Swiftie life, it's impossible to ignore the continually rising wave of her cultural power. Named 2023's Person of the Year by TIME Magazine, Taylor has more than earned her spot in a national conversation – and I bet you she's part of many conversations in your classroom.

And here's the thing: if your students are talking about Taylor, then so should you. This is an open door into engagement and skill building that is not to be missed.

In some ELA teacher circles, I see a hesitation to bring the world of pop culture into our sacred space of literature and critical thinking, but here’s the thing: pop culture and trending icons of the moment are vital tools in getting our students to cross that bridge from their worlds into the deep thought and skill practice that we want so much for them. It may be Taylor today, but keep your eye on other trends that can work in a similar fashion: to create a connection and start a deeper conversation.

Here are three ways to pull the power of Taylor into your classroom and spike engagement among your students:

I already LOVED teaching my annual Person of the Year assignment, but holy smokes, this year will lead to some exciting debate. Did Beyonce get the honor a few years ago? Nope. Did Taylor? She sure did. Last year's award went to the President of Ukraine as a war raged on, and this year's award goes to Taylor…as the world continues to fall apart.

The conversations and writing possibilities around this assignment are endless, but perhaps the most interesting conversation I've ever had with students was determining the criterion for “Person of the Year”. How can a pop icon win it one year, but political leaders earn it in another? What should be considered when choosing the “Person of the Year”?

Taylor Swift's commencement address at New York University has been a favorite of teachers for a long time. This assignment is a highly engaging way to get students to practice their rhetorical analysis skills and break down Swift's approach in sending off a class of graduating students. It’s inspirational for our high school students to envision this stage of their lives - whether or not students are college-bound. The speech is about moving into adulthood and holding firm to one’s identity - a message that will resonate with all students.

This lesson is wonderful to do as an introduction to rhetorical analysis (although it is a bit longer than I’d like — I suggest cutting it a bit) or to use independently as students are reviewing what they’ve learned about SPACE CAT and rhetorical analysis.

Here's what one teacher had to say about this lesson:

“My students LOVED this activity and had some really rich, analytical discussions as a result. I did end up modifying some questions, but this resource was invaluable. The kids were super engaged because Taylor Swift is either super loved or super hated.”

— Elizabeth E

If either of those two ideas aren't what you need right now, maybe this podcast episode will give you the inspiration you're looking for. A few months ago, I had the delight of collaborating on a Taylor-Made episode of The Spark Creativity Podcast. In the episode, I share an idea for using my rhetorical triangle graphic organizer with some of her songs for a quick and engaging lesson. Many more fabulous ELA authors contributed, so make sure to give it a listen!

I hope you've got some ideas now to capitalize on the Taylor energy that seems to always be around. Have a wonderful week at school!

LET’S GO SHOPPING

How to Create Book Club Magic Using Essential Questions {Part Two}

Lackluster literature circles? Boring book clubs? The remedy: lose traditional “role” sheets, declare freedom from organization by topic or genre, and build essential question-focused literature circles or book clubs instead. An EQ as the throughline for your lit circle/book club unit kicks up the impact that comes from having kids talk about what they read in a way that just does not happen with any other method. Here’s why…

Lackluster literature circles? Boring book clubs? The remedy: lose traditional “role” sheets, declare freedom from organization by topic or genre, and build essential question-focused literature circles or book clubs instead. An EQ as the throughline for your lit circle/book club unit kicks up the impact that comes from having kids talk about what they read in a way that just does not happen with any other method.

This is the second blog post in a series dedicated to this kind of magic. Make sure you catch Part One when you finish reading here!

REASON # 3 – BUILD COMMUNITIES WITHIN A COMMUNITY

Lit circles like “real” life book clubs

One of the great things about lit circles and book clubs is how they build communities within your larger classroom community.

In “real” life, we join book clubs to find community – to have a social outlet where we share a common interest. And even though lit circles have always had a cooperative learning element built in by design, using an EQ focus takes it beyond a learning strategy.

First, kids choose their book in a more authentic way, so regardless of how well they might know other students in their group, they have an immediate connection.

Second, like in “real life” book clubs where discussion is not dictated by a “role” but with genuine questions, connections, and a desire to understand, an EQ provides a touchpoint for question creation and passage selection. It also offers a way for groups to come back to center and ground discussions if focus waivers.

The work with supplementals and text pairings also offers students opportunities to build community as they try to make connections and develop understanding between texts, looking at “big” ideas through different lenses. Jigsawing between groups is a community builder, and EQs offer more opportunities for this because the text is not centered.

An EQ offers the opportunity for students to easily connect digitally. With no shortage of apps for virtual meetings, book groups can even be created between classes, providing alternative ways to foster and develop community.

As students share their thinking and debate and consider one another’s ideas, whether it is within their “home” lit circle or during a jigsaw, they learn from each other. They consider new perspectives. They lean on each other to understand and analyze the texts they read, creating a sense of belonging at a different level.

CHECK OUT AMANDA’S FAVORITE BOOKS TO USE IN An AMERICAN DREAM EQ UNIT:

REASON #4 – EASE OF ASSESSMENT

EQ = lit circle/book club assessment special sauce

How to assess students and what to assess them on is an often-cited source of frustration. You are not alone if you’ve worried about any/all of the following:

What if I haven’t read all the books?

How do I keep them accountable individually? As a group?

How do I know if they are reading?

Should there be a group assessment?

Projects? Writing?

But when your book clubs or lit circles are EQ-focused, they are skills-based, not text specific. And an EQ and backwards planning – knowing what your summative will be at the beginning of the unit – develops students’ skills throughout the unit so they can find success.

The focus of assessment, simply put, is to answer the essential question using whatever texts they encounter throughout the unit whether it is their novel, pairings or supplementals. Depending on your skills focus – developing interpretive-level questions, providing strong evidence to support thinking/writing/speaking, connecting concepts across multiple texts, paragraph writing – the summative could be:

a student-run Socratic with student-developed questions

a podcast

an analytical paragraph or essay

a synthesis essay

a one-pager

Throughout the unit, individual and small group check-ins could include:

written reflections

creating discussion questions and choosing passages for each meeting

write-arounds

hexagonal thinking activities

choice-board activities

and Sesame Street quizzes

that focus on the skills students need to practice as they work toward their summative.

EQ-focused book clubs and lit circles, like other EQ-based units, prioritize understandings about life that are bigger than the text/novel alone, making assessment more authentic and simpler to plan using backwards design.

CONCLUSION

EQ-focused lit circles or book clubs, by design, create an authentic, choice and skill-based, rigorous shared reading experience that your students will benefit from and you will enjoy guiding.

What have your experiences with book clubs/lit circles been like as a secondary English teacher? What questions do you have about EQs, backwards design, or EQ Adventure Packs? Let me know in the comments!

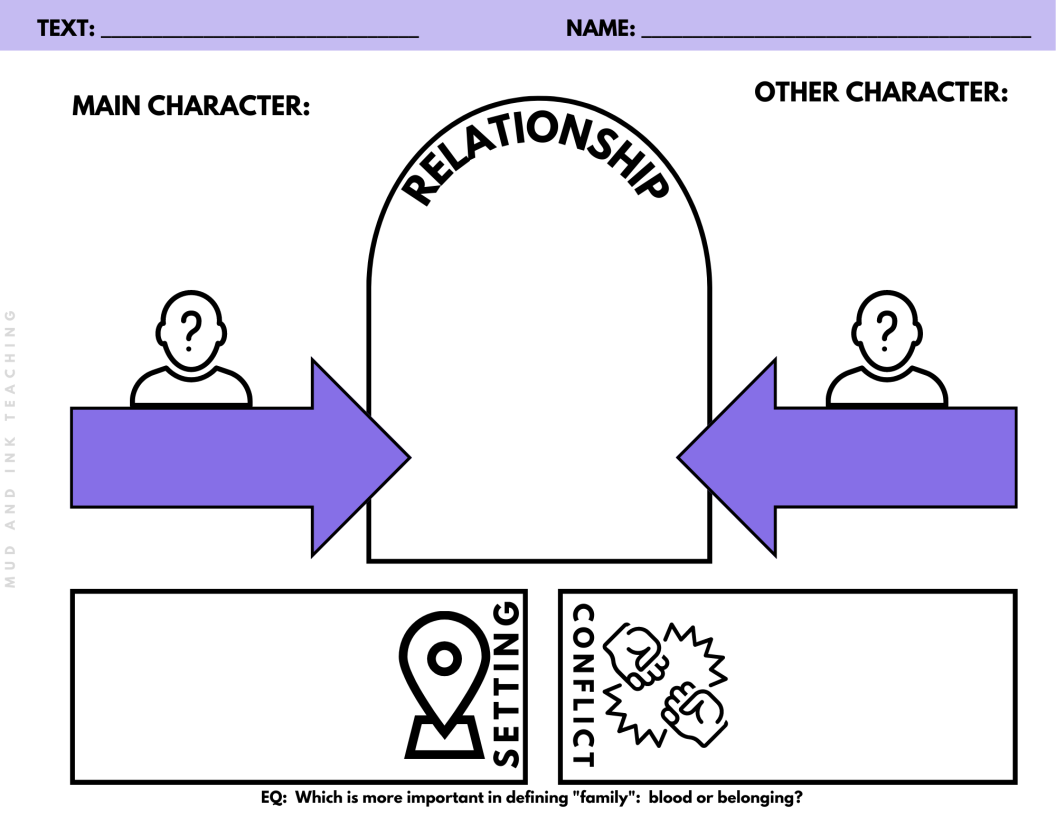

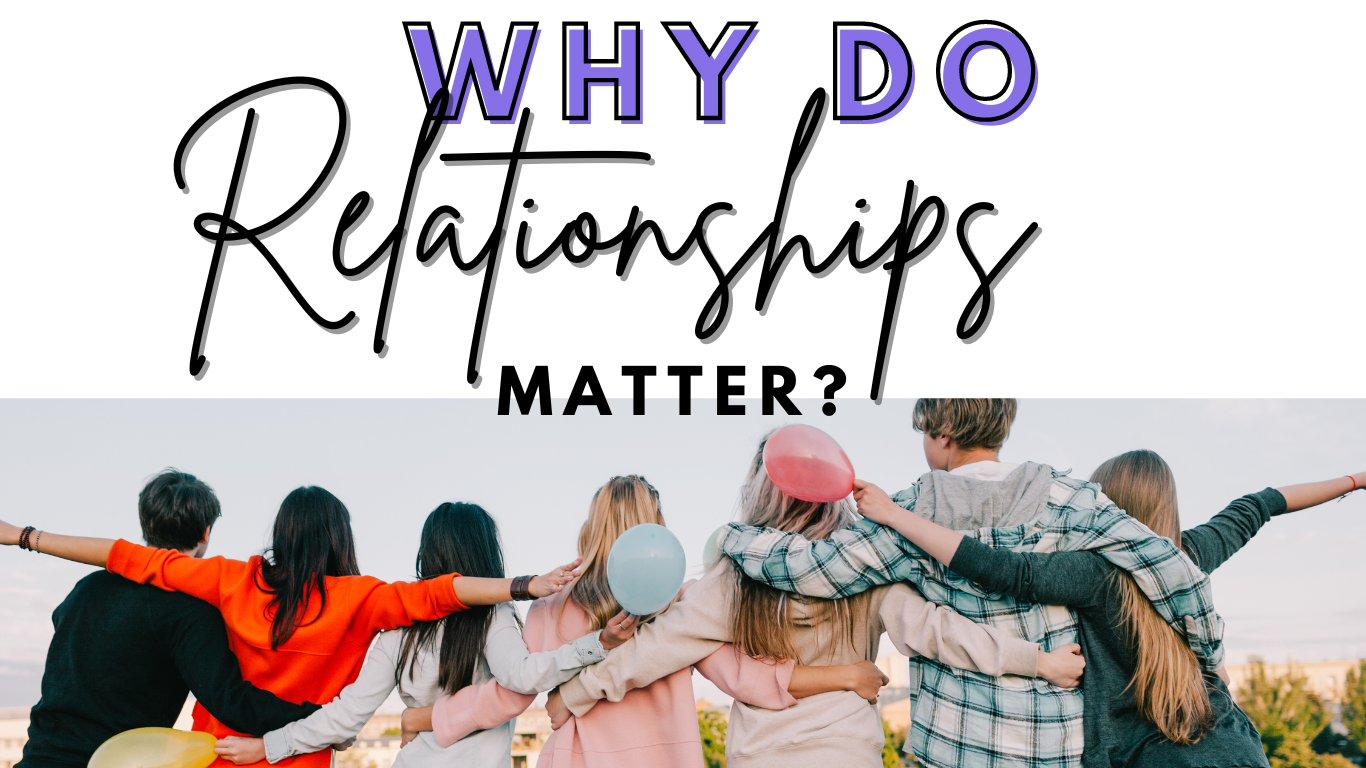

Curious about how the thought process goes into an EQ unit? Listen in here to get a feel for how I break down this EQ and the levels of complexity available to teachers and students with just this one question: Why do relationships matter?

Believe it or not, there are even MORE reasons to lean into an EQ-centered appraoch to lit circles, and there’s a PART ONE to this blog series! Did you miss it?

LET’S GO SHOPPING!

How to Create Book Club Magic Using Essential Questions {Part One}

Lackluster literature circles? Boring book clubs? The remedy: lose traditional “role” sheets, declare freedom from organization by topic or genre, and build essential question-focused literature circles or book clubs instead. An EQ as the throughline for your lit circle/book club unit kicks up the impact that comes from having kids talk about what they read in a way that just does not happen with any other method. Here’s why…

Lackluster literature circles? Boring book clubs? The remedy: lose traditional “role” sheets, declare freedom from organization by topic or genre, and build essential question-focused literature circles or book clubs instead. An EQ as the throughline for your lit circle/book club unit kicks up the impact that comes from having kids talk about what they read in a way that just does not happen with any other method. Here’s why:

REASON #1: CHOICE, BUT LIKE, FOR REAL

Fundamental Tenet of Lit Circles and Book Clubs

Fact: choice boosts student engagement. And even in the “passage picker, summarizer, questioner, illustrator” role sheet days of early lit circles, students selected books that most interested them – usually within a specific genre or topic.

Great, right?

Sort of.

What about students who:

detest dystopia?

hate historical fiction?

can’t stand “coming of age”?

They have choice. Among titles they wouldn’t otherwise pick for themselves.😕

When lit circles and book clubs focus on essential questions (more info on essential questions and inquiry-based learning here and here), novel options for students – unbound by any constraints other than shedding light on the question – grow exponentially!

For example, if your book club/lit circle essential question is why do relationships matter? book choices could include:

The Outsiders

The Hunger Games

and The Crossover

or

The House on Mango Street

Long Way Down

and The Children of Blood and Bone.

Classics. Novels in verse. Realistic fiction. Fantasy. Dystopia.

Something for every student's interest and background, and this is just a short list of possibilities for tackling this EQ! The EQ focus makes the book selection more authentic for the kids. Instead of “the least worst option,” their choice becomes something that truly speaks to their personal preferences as readers thereby creating more emotionally engaged lit circle/book club participants who are ready to tackle the EQ!

CHECK OUT AMANDA’S FAVORITE BOOKS TO USE IN A RELATIONSHIPS EQ UNIT:

REASON #2 – RIGOR

EQ-focused lit circles and book clubs elevate rigor!

While choice certainly helps open the door to student engagement, rigor plays a role, too. By rigor, I do NOT mean offering only complex texts, accelerated reading calendars, or piling on assignments.

As high school reading and writing gurus Kelly Gallagher and Penny Kittle say in their latest book, 4 Essential Studies, rigor does not equal text difficulty.

““Book clubs motivate us to read. They deepen our understanding of not only the book but how others read and interpret the same text … rigor is not in the book itself, but in the work the students do to understand it” (45-47). ”

And the work students do with EQ-focused book clubs or lit circles encourages this work.

Sure, in a genre-based book club, the kids can examine what elements show up in their book and how. They can compare how one author achieves this versus another.

But an EQ, like Which is more powerful: hope or fear? immediately asks students to sit with uncertainty and consider possible answers and solutions rather than identify more correct ones.

EQ-based lit circles or book clubs meet students where they are – literal, theoretical or anywhere in between – and provide opportunities to scaffold toward analysis, synthesis and more abstract thinking.

How?

One way is to use supplemental texts and pairings!

These texts are not novel-specific but EQ-connected, so every book group can use them:

articles

poems

songs/lyrics

art pieces

videos

stories

book excerpts

Supplementals and pairings can be used to create whole-class, lit circle-based, or jigsawed skill-focused lessons that students can then practice independently. Check out my EQ Adventure Packs for supplementals and pairings AND a choice board that can also be used for this purpose.

What might such a lesson look like?

Your EQ: what is more powerful: hope or fear?

Skill focus: writing analytical paragraphs (students hyperfocus on literal aspects of plot)

Whole group: listen to one of the songs, give kids a copy of the lyrics

Whole group: model identifying where you notice hope or fear in the lyrics; think-aloud noting which felt stronger and why

Small groups: kids continue identifying examples of hope & fear in the lyrics

Small groups: kids note whether “hope” or “fear” was stronger in each example

Small groups: select two lines/stanzas that best illustrate hope or fear

Post on Padlet

Whole group: debrief; model what a “good” reflection looks like; show a skills progression

Independently: kids draft a paragraph reflection on whether they felt fear or hope was a more powerful idea in song and why, using evidence from any of the groups’ findings.

This is just one way EQ-focused lit circles or book clubs can be rigorous while meeting kids where they are. The work they do in a lesson like this does not have a right or wrong answer; the kids discuss and rehearse their ideas and thinking aloud before they put pen to paper. The EQ requires kids to think beyond plot and surface-level similarities to do this work; it pushes them to consider ideas that are bigger than a text alone.

Listen in here to get a feel for how I break down this EQ and the levels of complexity available to teachers and students with just this one question:

Believe it or not, there are even MORE reasons to lean into an EQ-centered appraoch to lit circles, and there’s a PART TWO to this blog series! Are you ready for more?

LET’S GO SHOPPING!

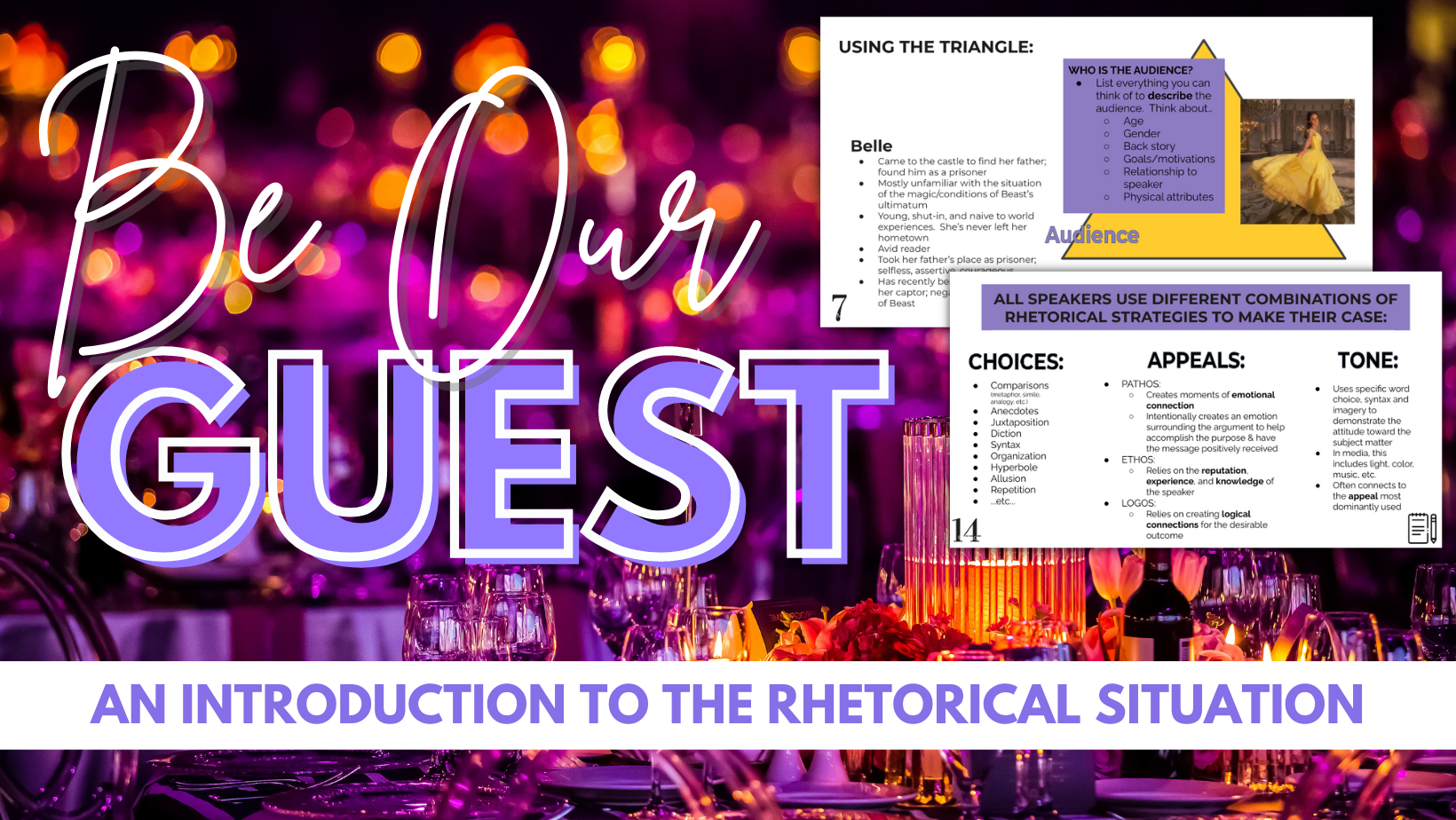

Teaching Rhetorical Analysis: Using Film Clips and Songs to Get Started with SPACE CAT

Try beginning your rhetorical analysis lessons by focusing on the rhetorical situation before heading into deeper analysis. When you’re ready, dig in using SPACE CAT and a great song from a musical that has a premise and an argument to examine. Here’s what we’ve done in my class using “Mother Knows Best” from Tangled.

Rhetorical analysis: so much more than commercials and appeals

Rhetorical analysis can get a stuffy reputation. Sometimes, we reserve it only for “serious” classes and students and we focus on monumental, world-shaking types of speeches. While this approach accomplishes a few of our long-term goals for education, it’s not doing enough to reach the masses of students who need these skills.

I hope you’re here reading this because you want to try RA with seventh graders. You want to introduce rhetorical analysis to your struggling 10th graders. I hope you’re here because you’re trying to do RA even though you haven’t been deemed worthy and been exclusively anointed as an AP Lang teacher. I hope you’re an AP Lang teacher here looking to do things with a broader scope and new entryways into conversations about complexity and sophistication.

Really, I’m glad you’re here.

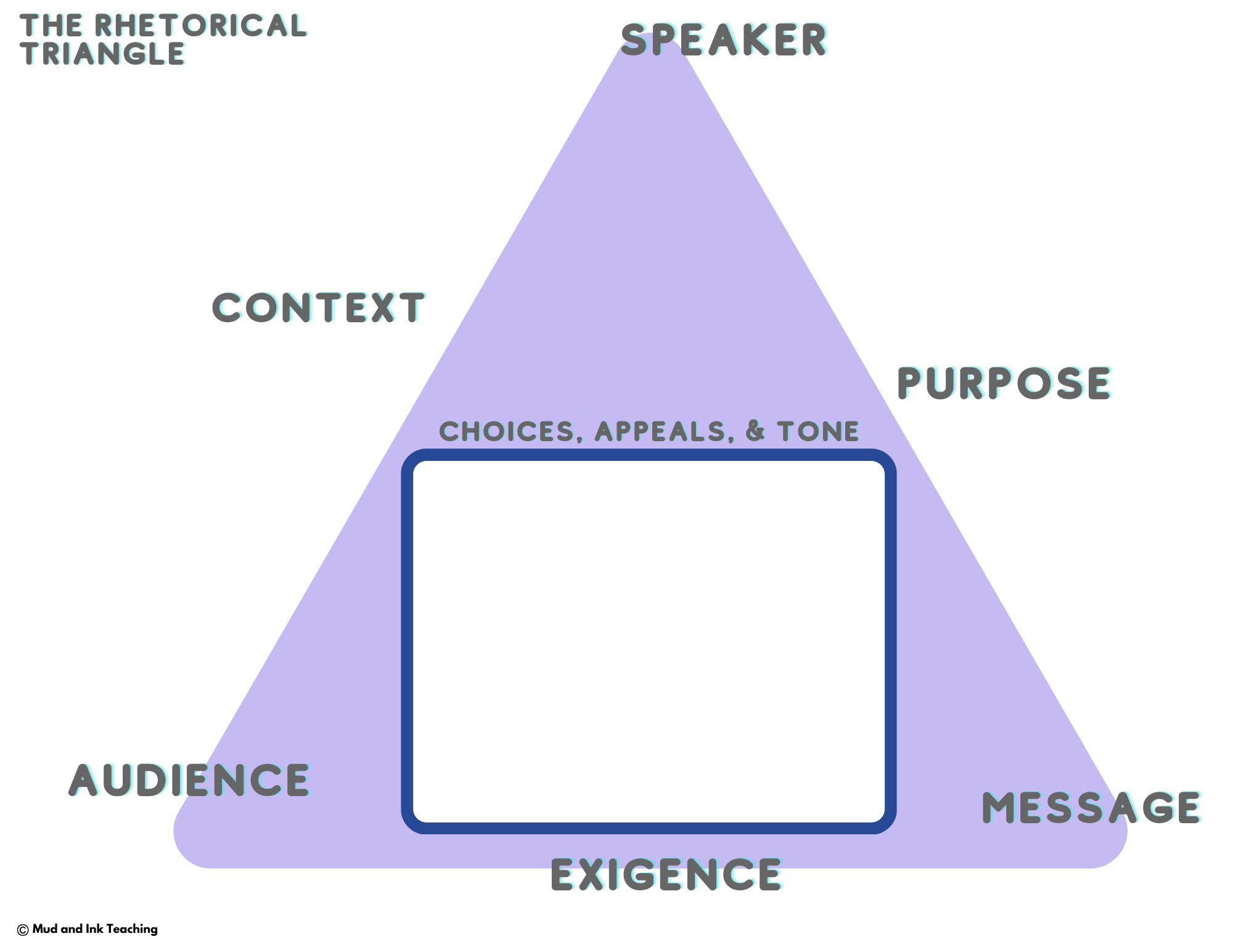

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: THE BASICS

Here’s where we need to start: the triangle.

Rhetorical analysis is less about appeals and more about the unique connection between three points: the speaker, the audience, and the message.

When we start RA zeroing in on ethos, pathos, and logos, we are playing a bit of a dangerous game. Teaching terms can be a comfort zone for teachers (we do this with figurative language, too). In our field, there are so few direction instruction content types of lessons, that it can feel cozy to snuggle up with a list of terms we understand and deliver them to our students. Without realizing it, we’ve created a pretty deep hole, jumped in, and forgot to throw down the rope ladder for when we need to get back out.

When we start with terminology, we’re sending the message to students that this is the primary focus of analysis: identification. We’ve armed them with dozens of terms, so the goal of analysis must be to slap these labels all over a speech and call it annotation. Then? It ends. Students falsely believe that they’ve accomplished the task because they did exactly what you taught them. They found the rhetorical questions. They found a simile. They found an example of ethos.

And then? We get really frustrated when they can’t tell us WHY, HOW, or SO WHAT when we probe them deeper about what they’ve identified.

This is my very long way of telling you this: DON’T start with terms, or, if you do, be ready to pivot quickly!

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: WHERE TO BEGIN

START with the rhetorical triangle or a framework that you like (I like SPACE CAT) and a conversation around the rhetorical situation (SPACE). By emphasizing the importance of understanding the components of the broader context of the argument, we help students start the probing question why? in the back of their heads as we go deeper and deeper into the argument itself.

One of my favorite pieces to use for practicing the rhetorical situation is looking at Lumiere’s plea to Belle in “Be Our Guest”. In another blog post, I outline how much there is to the situation -- there is so much to consider in terms of the speaker, the purpose, the audience, the context and the exigence. In the slide deck for this lesson, we spend a great deal of time listing as many details as possible before even looking at a single lyric. Why? Because once we get into the argument, we’re seamlessly moving through true analysis.

Ms. C? I think I found a simile.

What similie is that?

Well it says ____________.

Hmm.. You’re right. So why does this particular simile hold weight knowing what we know about who Lumiere is and what he’s trying to achieve in this moment?

Wheels turning…

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: GETTING INTO THE ARGUMENT

So we’ve got a handle on the rhetorical situation. That’s a win. In fact, that might be the entire goal of a unit if you’re just beginning. If your school is taking their time and truly working on vertical articulation, this is a great skill to introduce at 9th grade and build toward mastery in 10th.

But let’s say we’re moving on a bit and ready to analyze the argument. You might have a speech, a commercial, another song, or another type of fictional scenario, and now we need to look at the techniques used and do the analysis work.

This is where we come back to our analysis framework. I like using SPACE CAT, so this stage is where I rely on CAT: choices, appeals, and tone.

Rhetorical choices include just about everything, so it’s up to you to narrow the lane of what each argument is doing well. A rhetorical choice might be the structure or organization of the argument, an extended metaphor, the use of personification, or even a particularly interesting use of parallel structure. Appeals are what you think they are: ethos, pathos, and logos. And of course, tone is exactly what you think it is, too.

Not all choices, appeals, or potential tone words are important to talk about in every speech, so fully embrace your right to decide ahead of time which choices are on the table for discussion (this is called scaffolding and if you need help with it, I have a training in my Mastering Close Reading Workshop that you might find very helpful!).

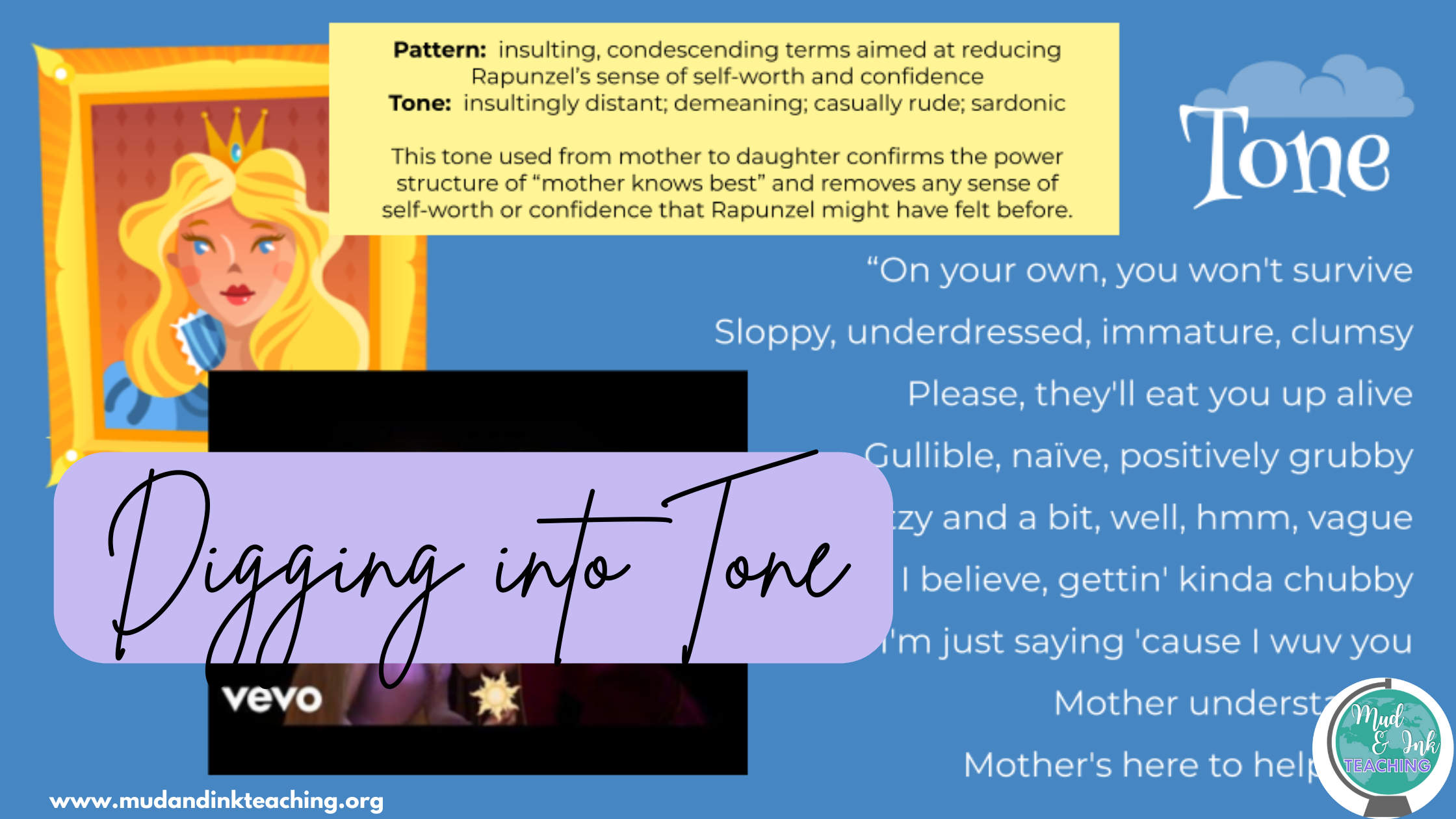

Let’s Look at an Example: “Mother knows best”

Here’s a quick example from “Mother Knows Best” in Disney’s Tangled for each of the components in CAT.

Mother Godel opens her song referring to Rapunzel “as fragile as a flower; still a little sapling, just a sprout”. She’s comparing Rapunzel to an undeveloped, extremely young plant.

She then uses the refrain “Mother Knows Best” along with other overly-assertive physical behaviors to assert her own ethos and Rapunzel’s lack of life experience.

The song also gives students the chance to look at tone, especially in the verse where Mother Godel tells Rapunzel that she won’t survive as a “sloppy, underdressed, immature, clumsy” and “gettin’ kinda chubby” girl out in the real world. This demeaning tone further underscores Mother Godel’s authority and increases the fear in Rapunzel about leaving her tower.

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: SO WHAT?

Well, we’ve arrived back where we started, friends. There’s a whole lot of highlighting, lots of phrases and details identified as one thing or another, but here comes the real work: SO WHAT?

So, Mother Godel uses a demeaning tone toward Rapunzel. So what?

She compares her to a “sapling” that has just sprouted from the ground. So what?

Here’s where we send students back to the rhetorical situation.

Support them through their “so what” with questions referring back to SPACE:

Why is this tone effective given what we know about the audience?

How does this metaphor create a sense of fear in Rapunzel?

How does Mother Godel’s use of hyperbole help her achieve her purpose?

Given the context of the situation, why would Mother Godel rely on the emotion of fear in this particular argument?

Once you’ve gotten through the SPACE, the CAT, and now arrived at the analysis part, remember that you can do this a few ways. Students oftentimes will write a paragraph of analysis, but if you’d prefer, you might have students complete a one-pager or just have a discussion that outlines what students could write about. It’s okay for some lessons to be heavier on the process than on the result.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS…

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: TRUST THE PROCESS

This is the process. It takes time, practice, and more practice. But if you are able to confidently lean on a framework that you like, provide the right types of arguments that meet students where they’re at, and stretch their work with rhetoric over multiple years, you’re going to find increasing success.

If you’re looking for more support, I have resources that are ready to help you. Keep doing the work -- I’m right here behind you every step of the way.

LET’S GO SHOPPING…

Three Myths about Close Reading

Close reading is often confused or made synonymous with things it most definitely is not, making it seem too scary to even approach. Maybe you’ve tried it, hit a wall of frustration and abandoned-ship. Well, it’s time to replace frustration, uncertainty and fear with the truth, and bust three common myths of close reading.

Three Myths about Close Reading (Busted!)

Wait, what? Close reading? That thing in Common Core everyone says they do but can never actually explain? If these sound like your thoughts, you’re not alone. And here’s why:

Close reading is often confused or made synonymous with things it most definitely is not, making it seem too scary to even approach. Maybe you’ve tried it, hit a wall of frustration, and abandoned-ship.

Well, it’s time to replace frustration, uncertainty and fear with the truth, and bust three common myths of close reading.

Three offenders.

Three stories that have run amok doing what myths do best – attempt to explain what we don’t understand.

But the thing is, close reading CAN be explained and understood, and there is a close reading reality. Let's talk THAT reality, so you can see the power this instructional strategy has to transform both your teaching of reading and your students’ growth and confidence.

MYTH #1: Close Reading = Reading an Entire Text

If the thought of figuring out how to teach a close read of an entire short story, or

an entire chapter OR

an entire article OR

an entire scene

gives you hives, well, that’s fair. It should!

If telling your classes to “do” a close read of X story results eye rolls, audible groans, and no sense of whether students are actually practicing reading skills – also fair.

This idea that close reading means scrutinizing an ENTIRE text is a complete and total, well, MYTH! It is also a recipe for overwhelm for both teachers and students, with little to no benefit for students’ growth as readers. Reading an entire text is just that – reading. And while there is nothing wrong with “just reading” that is not the purpose of close reading.

HERE’S THE REALITY: Close Reading = Reading a Passage

Close reading is re-reading with intention, with the purpose of practicing skills, learning patterns and deepening understanding. So instead of an entire text, choose passages no more than a page long, maybe going onto the back, for your lessons.

Begin by having students read a longer chunk: a chapter or chapters, an act, a short story – either for homework or independently during class – of which the passage is part. When the kids come to the close reading lesson, it will be at least their second encounter with said passage.

Pffft, you might be saying. My students aren’t going to read that longer chunk independently.

That might be true. But they can still do the lesson.

Close reading lessons are always in-class, skill-focused, teacher-directed experiences. Keeping the passage short allows students to do the lesson whether or not they completed all of the prior reading. The passage is read, and often re-read, in class, so you know, at the very least, even if students read nothing else for an entire unit, they have read those close reading passages and practiced skills.

Length is critical, and to keep passages short, it is not only ok but necessary to eliminate content that does not help students practice the skill. Consider what is most important and what is necessary for student practice. Then decide how much to include before and after. Context can always be provided by you for the kids in the lesson directions.

MYTH #2: Close Reading Prioritizes Reading the Whole Text

Your reading curriculum contains four core novels and a Shakespearean play. The best way for students to grow as readers, writers, and thinkers is to make the text central to learning. They must read every page and every word of every novel and the play in order to make progress. Frequent comprehension quizzes are the way to keep them accountable.

Close reading is reading EVERYTHING – page one to page end.

Um, no. Just NO. To ALL of that.

HERE’S THE REALITY: Close Reading Prioritizes Skills

Close reading DOES NOT – like, to infinity DOES NOT – center the text.

Close reading centers SKILLS.

The text is the vehicle through which skills are taught. Don’t get me wrong, the text is important, but students are not being assessed on whether or not they “know” the whole text. They will be assessed on the skills you taught and that they practiced during your close reading lessons.

Skills can run the gamut – from rhetorical situation to recurring symbols, to use of imagery – depending on the type of text, your essential question (more info on this here), and your summative assessment. The skills determine the annotation focus(es). Remember, though, not to get carried away in asking students to annotate for all the things. Less is more.

Make it super clear in your directions what you want them to annotate for. Without this, students end up randomly highlighting and labeling with no sense of how or why it all fits together. Instead of wild goose chase annotation, send students on a purposeful, scaffolded path toward analysis.

MYTH #3: Close Reading Answers A Set of (Text-Dependent) Questions

You are at the photocopier and find a handout titled, “Close Reading Questions.” You look through it and consider that maybe this is close reading.

Nope. Not even kind of.

HERE’S THE REALITY: Close Reading Works with Essential & Analysis Questions

A list of teacher-created questions for students to answer as they read a text – or after they read it – could maybe be considered “guided” reading. But it is not close reading.

Close reading does involve questions, but they are of the essential and analytical variety. And you come up with them before students close read anything. These are the questions that drive your unit and skill focus. They are the questions that inform your backwards planning: what it is you want students to know or do by the end of that unit?

Your close reading lesson passages should all connect to your unit essential question (more on EQs here), so that they build on each other, which results in students building their learning – comprehension, pattern recognition, deep thinking – over time.

And within each lesson, you create an analysis question for students to work with at the end. When planning a close reading lesson, come up with this question first. Consider what you would look for in the passage to answer it. This will help you come up with student annotation guidelines. Having kids draft a skills-focused analytical paragraph to answer a question using their close reading annotations helps prepare them not only for a summative task, but makes them derive meaning, instead of searching for a “correct” answer.

So, yes, questions, BUT questions that require students to make meaning using the skills they practiced in that close reading lesson for that particular passage, not to hunt and peck through an entire text to find “the answer.”

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS…

Close reading is not its mythology! It is not reading an entire text, it is not whole-text centered or answering a set of text-dependent questions. Close reading reality decenters the text, prioritizes skills, and uses essential and analysis questions to drive learning. This instructional strategy has the potential to move mountains for your students as readers, writers and thinkers and for YOU as a teacher of reading.

If you haven’t tried close reading before in your classroom or if you’d like to revisit it after a less than positive experience, grab this free video where I go into more depth about the what, why and how of close reading. What has been your experience with close reading? What questions do you have?

LET’S GO SHOPPING…

How to Throw a Gatsby Party as PreReading Strategy

Teaching The Great Gatsby is a massive task, but setting up students during prereading is a critical moment to help them feel successful as they’re tackling the novel from the start. Here’s how to use a Gatsby Party as a stations activity that helps students get to know each of the major characters in the novel.

How to Throw a Gatsby Party as PreReading Strategy

There is no shortage of blog posts in the world about English teachers throwing Gatsby parties for their classes before or after their study of the great American classic. What I want to show you here is how you can use this party as a gateway activity to the book and a prereading strategy that sets students up for early success in reading. So, instead of waiting until the very end of the unit to celebrate, let’s start things off with a classroom transformation that will engage students from the start!

Shop all of my Gatsby party essentials on my Amazon Storefront

WAIT! DO YOU HAVE A COLOR SYMBOLISM TRACKER TO USE FOR YOUR UNIT? GRAB THE ONE PICTURED ABOVE RIGHT HERE AS MY GIFT TO YOU!

SHOULDN’T PARTIES BE FUN?

Yes! No matter when, where, or how you throw your party, there should be plenty of fun. Of the many goals of the party, getting students hyped up to read and feeling the energy of the story, is a huge priority. If you have some money to spend, spend it on items that can be reused for a few years -- that makes the investment worth it. You’d be surprised at how a Dollar Tree raid can add up and then at the end of the party all get thrown away and be completely disposable.

Era costume pieces, tapestries to hang as backdrops, photo props, or even centerpiece items from thrift shops are things that can be packed up and used year after year. I like these posters ($10) and once they’re laminated, they’ll last forever. Here is a huge collection of ideas that I have stored on my Amazon Storefront — I like to use this as a vision/mood board while brainstorming what I’ll do each year.

If you’re not going to spend any of your own money, there’s plenty to do to set the mood for free: YouTube playlist of music from the movie or Jazz Age music, cover your whiteboard in hand-lettered quotes, grab white paper from the supply closet for tablecloths, etc. I even make my students invitations to the party and hand them out a few days ahead of time. Most of them look at me and roll their eyes, but enough of them appreciate the dorky gesture.

Embrace the Thematic Tie-ins

The Great Gatsby is rife with themes that resonate with students - the American Dream, social class, love, and the illusion of happiness. Use the party as a springboard to introduce these themes in a subtle yet engaging way. Consider incorporating décor or activities that hint at these concepts. For example, you could have a "Dream Wall" where students write their aspirations before they’ve even started their discussions about dreams (and their potential to inspire or destroy). By weaving these themes into the party, you're not only setting the mood but also planting seeds of inquiry that will bloom as students delve into the text.

PREREADING WITH STATIONS

Now that you’ve set up the energy and atmosphere of the party, it’s time to do the behind-the-scenes work of getting students ready to read. For those of you reading this post who prefer to do your party at the conclusion of the novel, consider moving it to the beginning of the unit instead.

HERE’S WHY YOU SHOULDN’T WAIT:

Authenticity & Joy: Classroom transformations like a Gatsby party serve as a seamless way to pique interest in an authentic way.

Frontloads Key Information: By introducing students to the characters, setting, and themes at the outset, you give them a foundation to build upon as they read. This empowers them to make connections and comprehend the text more deeply.

Creates Anticipation and Excitement: A party atmosphere generates buzz and curiosity about the story, making students eager to dive in and discover what unfolds.

Sets a Collaborative Tone: The interactive nature of stations encourages discussion and teamwork, establishing a positive learning environment for the unit.

Enhances Engagement from the Start: Immersive experiences like a Gatsby party are more memorable than traditional introductions, capturing students' attention and motivating them to actively participate.

Builds Schema: The party helps students connect their prior knowledge and experiences to the novel's context, making the content more relatable and accessible.

As I set up my room, I create 5-6 large tables that I’ll use as the stations. This blog post will walk you through everything that I do in my lesson which can be found here completely ready for you to print and use!

Never used stations before? I’ve got a quick and easy guide to using stations here as well as how I use this learning strategy for back to school here!

Designing Stations to Support Readers

Whether you’re doing prereading stations for Gatsby or any other book, you need to consider what students need to support their reading experience. In the case of Gatsby, I’ve found that the earliest struggle students have with the novel is knowing who is who. Because of this, four of my stations are designed as “Meet the Character” stations. I pull a passage of description of Nick, Gatsby, Tom, and Daisy. At each of these four stations, students read the passage “meet” the party guest, and then jot down a record of their initial impressions of who they just met at the party.

This is a quick (but important) prereading exercise disguised by fun. In the passage selected for each character, students are getting:

Familiarized with Fitzgerald’s language

Context around each character’s personality

Basic characterization

These may seem like small things, but in the world of reading comprehension, they’re critical. Imagine reading Gatsby for the first time completely blind to the story. Now, imagine reading it witht the mood of the party that you’ve created and an initial understanding of the personalities and roles of each of the main characters. This is a huge win!

OTHER NON-CHARACTER BASED STATIONS

The other stations are flexible. Here are a few other ideas I’ve used:

Shop my Amazon Idea List

Book Cover analysis: have students look at various different versions of published book covers. What does the art reflect about the focus of the story? How does the artwork make you feel in terms of what mood you’re expecting to encounter? What are the colors used in each? How might that be reflective of the story you’re about to read?

Setting analysis: Choose 1-2 passages that capture important setting descriptions. Where will this story take place? How does the energy of the setting match or seem different from that of our “Gatsby Party” atmosphere? What are the colors, textures, sounds, smells, and visuals included in the description? You can even have students attempt to draw exactly what they’re reading in the description for an added “party game”.

Music/lyric analysis: Pull a Jazz age song and its lyrics for students to read and analyze. What were the values of this type of music? What did the music center? What kind of energy does this music give?

Trailer analysis: Set up one table with several of the Gatsby film trailers pulled up. Students can compare and contrast, make predictions, etc.

The Mysterious Gatsby Station: Compile a collection of rumors and gossip about Gatsby from the novel. Have students read these snippets and create a "Wanted Poster" for Gatsby, highlighting his enigmatic persona and the questions surrounding him.

Symbolism Scavenger Hunt Station: Hide various objects around the room that symbolize key elements in the novel (e.g., a green light, a clock, a pair of eyes). Have students find these objects and speculate on their potential significance.

Roaring Twenties Slang Station: Provide a glossary of 1920s slang terms. Have students translate a few passages from the novel or create their own "flapper" dialogue.

The Ripple Effect

Remember, the Gatsby party isn't just a one-off event. It's a catalyst for deeper learning and engagement. The enthusiasm and curiosity generated during the party will carry over into your subsequent lessons, making the study of The Great Gatsby an unforgettable experience for your students. Don't be afraid to get creative, think outside the box, and tailor the party to your students' interests and your teaching style. By setting the stage with a memorable and meaningful experience, you're paving the way for a literary journey that will stay with your students long after the final page is turned.

If you’ve been partying at the end of reading Gatsby and still love it, by all means, continue to do what brings you joy! But I do hope that at the very least, these character stations activity will provide a strong foundation for your readers at the start of the study of the novel. I’d love to hear about your experiences in the comments below!

Ready to think more through the Gatsby reading experience? Watch below!

LET’S GO SHOPPING…

Unit Makeover: The Short Story Unit in Secondary ELA

Short story units have the potential to deeply inspire and impact learning with students, but if the approach is disjointed or lacking any sort of alignment, these units can feel like flops. Here are the ways that I craft meaningful, engaging, and interesting units to highlight the short stories that we love (and a few more that we should add to the rotation!)

Unit Makeover: The Short Story Unit in Secondary ELA

When is the last time you sat down for a meal where your server recommended a very specific bottle of wine to match the meal you were considering on the menu? The perfect Argentinian Malbec to compliment the perfect marbled ribeye. And when is the last time you tasted that symphony of flavors? The melting, fatty salt of the meat on your tongue is followed by the gentle swirl of the deep red wine just after.

Maybe you’re a vegetarian and ready to never come back here and read another article from me again, and I understand (this is not the first time that I’ve used a metaphor about meat. Hmmm…), but if you’re willing to hear me out, here it is:

Disjointed experiences are fine, but intentionally, purposefully blended ones are so much more memorable.

This is precisely how I feel about unit planning and especially the notoriously predictable plan that every English teacher since the dawn of time seems to design: UNIT 1 - SHORT STORIES.

THE DISJOINTED SHORT STORY SCENARIO

The idea for this unit seems logical on paper: start the year with some shorter texts to warm back up, review everything students need to know for the year coming up, and presto! Ready to take on the year. But after experiencing this myself and talking to hundreds of other teachers, there are a few notable problems:

PROBLEM 1: Lack of connection

Short stories don’t naturally connect to one another just because they are short stories. So when we begin these units thinking about the skill review component, we are often blindsided as the unit is in progress feeling like it’s clunky and lacks flow. Without the feeling of connection, these units can be difficult to navigate in terms of pacing and engagement.

PROBLEM 2: Lack of representation

The most commonly anthologized stores also tend to be Euro-centric, male-authored stories. We have a responsibility to do better for our students and to have their own voices, stories, backgrounds, and experiences represented and included in everything we do. This means branching outside of the short stories most frequently recommended by text book companies and doing some of our own research to find new, fresh voices.

PROBLEM 3: Lack of variety

One teacher wrote to me saying: “I do run into trouble when I try to use short stories that are available on CommonLit. When I've tried to use them in the past--some are amazing short stories, like "The Landlady" and "The Intepolers"--the kids complain that they've already read them! UGH”

Does this sound familiar? Since starting the year this way is so popular and databases like CommonLit have come around, teachers sometimes find themselves going to the same places for ideas and then repeating stories.

PROBLEM 4: Trying to cover too many skills

Sometimes the nebulous goal of “reviewing literary terms” stretches student focus too thin. Attempting to use one single unit to cover a dozen or more terms ends up giving us more attention to breadth rather than depth.

Specific EQ Unit & Text Set Pairings:

To solve many of these problems with the traditional short story unit, I recommend implementing an Essential Question to drive the unit. Short stories need to be contextualized, and using an Essential Question connects the dots and creates meaning. The art of writing an essential question takes into consideration three key components: text(s), themes, and skills. Essential questions should drive genuine curiosity and be exciting for students to explore, discuss, debate, and return to throughout the year.

Below, I’ve drafted a few examples of EQs that could theoretically be used at the start of a school year. You’ll notice a few things:

The question anchors the unit. From introducing the question to assessment, the question is the driving force that connects all texts and activities.

Instead of teaching short stories and a variety of random literary terms, the unit is cohesively driven by a more narrow focus.

The EQ gives direction for the unit without being prescriptive. The suggestions I have here are flexible and adaptable to different grade and difficulty levels.

In each of the example units below, I’ve provided a mixture of the most commonly used short stories that you may have from anthologies or prescription curriculums blended with new ideas, short film, music, and other genres to further address the complexity of the EQ. Be sure to check out Episode 107 of the Brave New Teaching Podcast to see how this method was applied in Marie’s class!

Here are a few example ideas to get started:

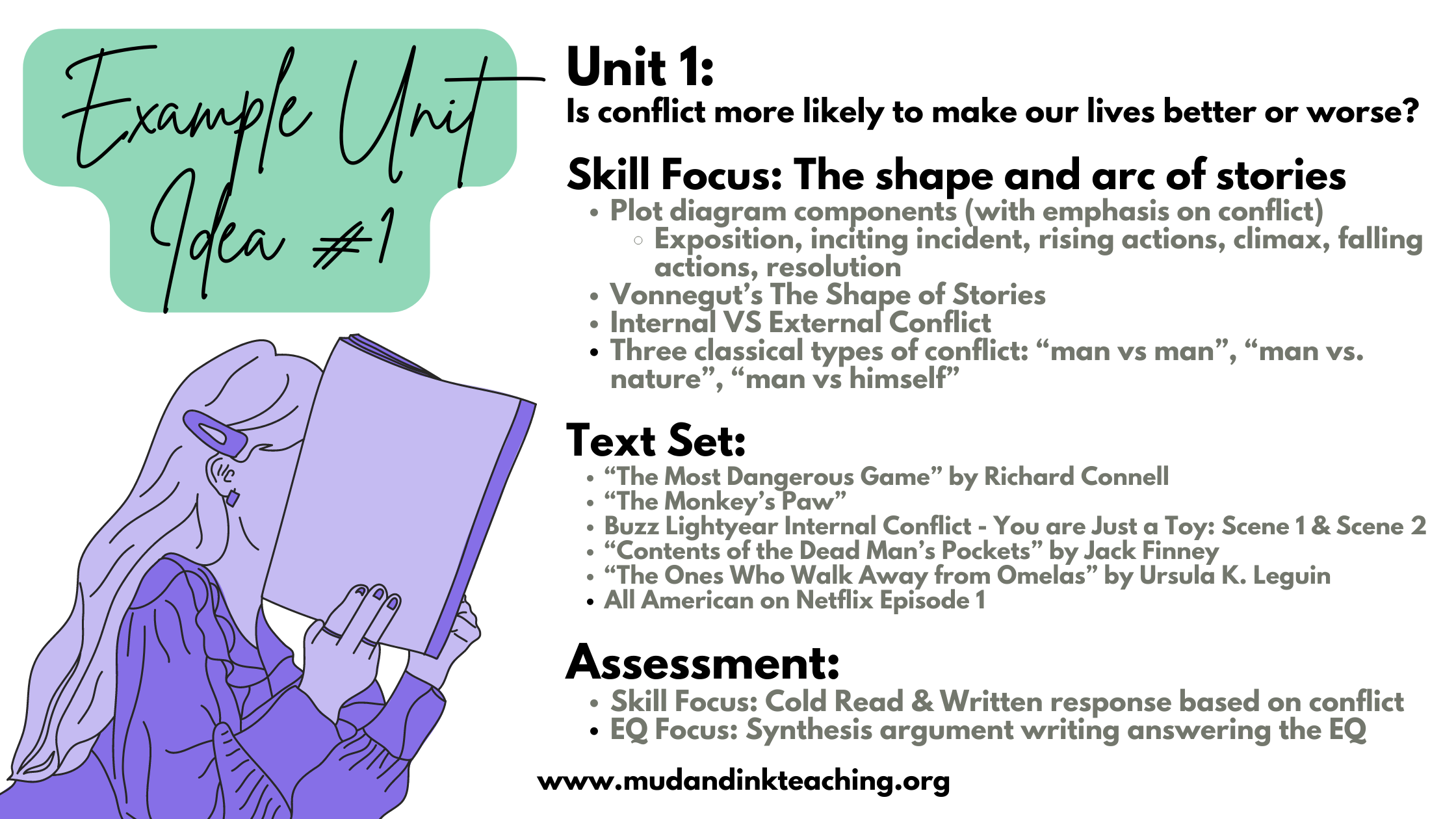

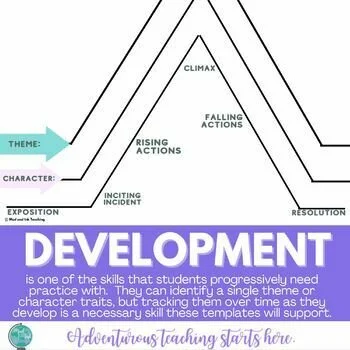

Example #1: Connected by a skill/standard

Unit 1: Is conflict more likely to make our lives better or worse?

Skill Focus: The shape and arc of stories

Plot diagram components (with emphasis on conflict)

Exposition, inciting incident, rising actions, climax, falling actions, resolution

Vonnegut’s The Shape of Stories

Internal VS External Conflict

Three classical types of conflict: “man vs man”, “man vs. nature”, “man vs himself”

Text Set:

Buzz Lightyear Internal Conflict - You are Just a Toy: Scene 1 & Scene 2

All American on Netflix Episode 1

Assessment:

Skill Focus: Cold Read & Written response based on conflict

EQ Focus: Synthesis argument writing answering the EQ (utilize personal experience and texts from the unit to answer EQ)

Example #2: Connected by genre

Unit 1: To what extent does gothic fiction reveal the human condition?

Skill Focus: The elements of gothic fiction

Author’s use of tension

Author’s use of tone/mood

Setting

Text Set:

Excerpt from Mexican Gothic by Sylvia Moreno Garcia

Various scenes from The Phantom of the Opera

Assessment:

Skill Focus: A project-based assignment where students analyze the connection between tension, mood and setting (a recreated scene and written analysis; a living tableau; an artistic interpretation)

EQ Focus: A literary analysis writing that hones in on one of the stories and the gothic elements that reveal the human condition

Need to teach plot elements?

Example #3: Connected by another genre

Unit 1: How does dystopian fiction use the present to predict the dangers of the future?

Skill Focus: The elements of dystopian fiction

Characteristics of a dystopian protagonist

Author’s use of tone/mood

Setting

Imagery

Text Set:

“There Will Come Soft Rains” by Ray Bradbury

“The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson

“Harrison Bergeron” by Kurt Vonnegut

“The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” by Ursula K. LeGuin

Assessment:

Skill Focus: Cold Read & Write: How does the author’s use of genre elements / setting / imagery / use of tone/mood in order to warn about the dangers of the future?

EQ Focus: Research project: select a present problem and predict the dystopian future to come from this issue

Example #4: Connected by a theme

Unit 1: Which is more impactful in a child’s coming of age: the influence of family or the physical environment around them?

Skill Focus: Elements of coming of age genre

Setting

Characterization (direct & indirect)

Text Set:

Assessment:

Skill Focus: One Pager - Choose one character to place at the center. Surrounding the character, add evidence of coming-of-age moments, setting, etc. that have influenced their development

EQ Focus: Synthesis Argumentative essay responding to the EQ using the short stories from the unit

Example #5: Short Stories Reimagined in Fairy Tales

In episode 107 of the Brave New Teaching Podcast, I chat with my cohost Marie Morris about the process of tackling a unit makeover with short stories. Listen in to see how we resolved so many of the problems (at the top of this post) and built a Fairy Tale Unit that completely revamped the level of engagement while still tackling all of the skills that mattered the most.

No matter how you tackle your unit makeover, consider the power of that Essential Question to give the context your unit needs. I’d love to hear how you tackled your own makeover, so be sure to leave a comment below!

TRY AN EQ ADVENTURE PACK!

These units are packed up and ready to teach! They are seamlessly aligned with a juicy Essential Question, supplemental texts, and plenty of templates to use in tandem with whatever short stories or novels you have on hand. Check them out right here!

LET’S GO SHOPPING…

Getting Books with LGBTQ+ Protagonists into the Hands of All Students

Having your shelves stocked with LGBTQ+ protagonists and stories is great, but if students don’t know they’re available, don’t have a safe time to check them out, are intimidated by the cover, or simply don’t feel comfortable checking the books out, then the diversity of the library doesn’t really matter! Here are five steps to take to make sure those wonderful books actually make it into the hands that want them and need them.

This is a post from guest teacher-author John Rodney.

Getting Books with LGBTQ+ Protagonists into the Hands of All Students

Many teachers are creating LGBTQ+ inclusive classroom libraries that speak to the many identities of their LGBTQ+ students. Teachers are seeking out stories that feature LGBTQ+ protagonists in diverse storylines across genres. They are choosing stories with care to ensure that restrictive gender stereotypes are not reinforced and that intersectional identities are represented. They are putting stories that move past LGBTQ+ trauma on their classroom bookshelves.

Teachers are doing all this amazing work, and yet, despite all of this, the books remain on the shelves untouched. There are many potential reasons why students are lining up to check out these books. I want to give some steps that teachers can take to help get books into the hands of students which is exactly where we want them!

#1: Advertise. Advertise. Advertise.

Books featuring LGBTQ+ protagonists should not be separated from other books. They should be put alongside all the other books for young readers, LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+, to discover and enjoy. They should be organized however that teacher may organize their library: by genre, alphabetically, etc.. This is an important symbol to students that these characters and storylines are just like every other character and storyline and deserve to be read and enjoyed. This seems like a great idea, doesn’t it? It is! Now, why might this be preventing students from reading these books? One of the issues is that the students who may be impacted the most by these books don’t know they exist. They don’t know that your bookshelves are ones that have stories that feature LGBTQ+ characters in them. One way to solve this is to step up advertising of these stories and let kids know where they are if they wish to read them. Advertising is not a one-time thing. It needs to be done repeatedly throughout the school year so that when students are finally ready to hear you, they know they have options in your classroom library to explore. When you think you’ve done enough, do a little more.

There is some debate amongst teachers that perhaps there should be identifiers of the LGBTQ+ books on the bookshelves like putting rainbow stickers on the bindings, so students may find them more easily or to separate the books entirely into their own section, so students would know where to find them. I totally get this and have contemplated it in the past myself; however, in the next section, you’ll find why making an identifiable marker for LGBTQ+ books that is recognized class-wide may negatively impact the students you are trying to help.

#2: Judge the risk by the cover.

Teachers want their students to be their authentic selves. They want students to feel an immense sense of pride in who they are; however, coming out (the act of publicly identifying yourself as a member of the LGBTQ+ community) can be a very difficult experience for young people in middle and high school. In many student’s experiences there is constant taunting and teasing for those who may not fit into what is characteristically considered masculine or feminine. The straying from norms places a target on them for harsh ridicule. A student does not actually need to be part of the LGBTQ+ community to be targeted, they just need to be perceived as one.

If students are looking to explore their identity through literature, through the books on your classroom bookshelves, it needs to feel safe to them. This is where covers of books need to be considered. For a student who is just beginning to understand who they are and wishes to read about LGBTQ+ characters or for a non-LGBTQ+ student who wants to read a good book that features an LGBTQ+ protagonist, having a book with rainbows (symbol of the LGBTQ+ community), characters breaking stereotypical appearance gender norms, or characters expressing same-gender affection on the cover can feel extremely dangerous. A book with a cover that represents an LGBTQ+ protagonist could out a child (reveal their identity as a member of the LGBTQ+ community) or have their sexuality/identity questioned. They may face severe social and physical consequences from friends and family. Be aware of the risks a child is taking to pick up that book from your classroom bookshelf when selecting which books you’ll offer.

#3: Set aside time for student to check out books when there isn’t an audience.

When some students are choosing books that feature LGBTQ+ protagonists/storylines during class, they feel like the whole world is watching them. They feel like the second they touch the book with an LGBTQ+ protagonist, a siren will go off, a spotlight will be put on them, and they will be outed or have their identity questioned and ridiculed. Why would they risk it? Many times, they don’t, and the book that could really benefit them is left on the shelf unread. Building in time during the day or the week for students to come in when others are not present is something that could get a book into the hands of a student who needs it most. This should be a part of the schedule that you create for your students so that any student can take up this opportunity.

#4: Celebrate LGBTQ+ characters, storylines, and authors.

Many ELA teachers find ways to try to engage students to inspire a life-long love of reading. They find ways to expose students to stories and genres that they normally would not gravitate to and create a curiosity within them to read. Be deliberate with the books that you are choosing for these activities; include LGBTQ+ protagonists and authors.

If you are performing “First Chapter Fridays” in your classroom, choose a book that features an LGBTQ+ protagonist. Project the cover of the book for the students to see along with a picture and brief biography of the author. Make sure to identify the LGBTQ+ identity of the author, so students understand this part of their identity.

If you are doing a “Book Tasting,” include a variety of books featuring LGBTQ+ characters and storylines across genres for the students to read and try out.

These types of activities give LGBTQ+ students and non-LGBTQ+ students opportunities to discover stories they may want to read, and it gives them a sense of pride seeing storylines fromt communities they, friends, or family members are a part of. This could make kids aware of stories open up their minds, and increase the rates at which books are checked out.

#5: Normalize the reading of LGBTQ+ books by non-LGBTQ+ students through classroom activities.

An idea that many young people have is that if a student reads books with an LGBTQ+ protagonist, the student must be queer. They ask themselves:

Why would a student read a book about a queer/gay/transgender person saving the world in a science fiction book when they could just read a “normal story” with a straight person doing it?

Why would a young person read a same gender love story when you could just read a “normal love story”?

Why read an autobiography about a LGBTQ+ person when you could read about a straight person?

This mentality can be combatted by exposing and normalizing literature by LGBTQ+ authors featuring LGBTQ+ protagonists being read by every student in the classroom.

Identifying theme through picture books? Use one with an LGBTQ characters.

Reading circles? Provide options which feature LGBTQ+ protagonists.

Compare and Contrast Paragraph? Use a short story or film that features an LGBTQ+ character to serve as the basis for the assignment.

Biography Unit? Include options of LGBTQ+ people from your bookshelves for students to read and write about.

If every student in class is reading a short story or a book by an LGBTQ+ author which features an LGBTQ+ character, then it isn’t an LGBTQ+ thing. No one is a target. No one is ridiculed. It’s just normal. It’s what students in your class do. This will empower students to pick up these stories and books own their because that’s what students do in your class. They read all stories.

This list of ways to get LGBTQ+ stories into the hands of students has not been exhausted by any means. There are so many ways to thoughtfully set up systems and build classroom culture that normalizes getting books that feature LGBTQ protagonists and storylines into the hands of all students. That is where they will do their most important work. It is where they will have the most impact.

Check out some LGBTQ+ books to add to your classroom library.

The following are affiliate links from which the author will earn a small commission from your purchase

LGBTQ+ Children's Books: https://a.co/1HIU1lm

LGBTQ+ Middle Grade Books: https://a.co/geHRTkV

LGBTQ+ Young Adult Books: https://a.co/4GeELKK

MEET OUR GUEST CONTRIBUTOR:

John Rodney has been a secondary English educator for the past 15 years at both the middle and high school levels in Southern California. For inclusive practices, relatable experiences, classroom tips, and good laughs follow him on Instagram at @teachertoteacher, TikTok at @teachertoteacher, and Twitter at john_j_rodney. He would love to connect with you.

LGBTQ+ Stories Belong in Your Classroom Library

Each year teachers welcome new students to embark on amazing learning journeys in ELA classrooms. Teachers try as hard as they can to provide activities that engage students, introduce new skills, and create environments that are welcoming to all students. Here are five ways to make sure that happens for LGBTQ+ students…

This is a post from guest teacher-author John Rodney.

LGBTQ+ Stories Belong in Your Classroom Library

Each year teachers welcome new students to embark on amazing learning journeys in ELA classrooms. Teachers try as hard as they can to provide activities that engage students, introduce new skills, and create environments that are welcoming to all students.

In recent years, a question has been posed causing teachers to aim their critical eyes at their own practices, activities, and classroom environments: Is your classroom truly a place that celebrates the identities of ALL your students?

Teachers want to do what is best for all of their students, so they are reflecting more closely on what is going on in their own classrooms. They are

looking at the literature shared.

looking at the physical and culture created.

looking at the classroom library books offered.

looking at the materials prepared.

looking at the practices implemented.

Amazing teachers are thoughtfully reflecting on the question and readying themselves to take action to improve the validation of their LGBTQ+ students’ identities in their classrooms, and I’m here with your first step. There are so many ways to increase LGBTQ+ inclusivity in schools; however, I would like to provide a few steps that focus on one of the most treasured spaces in an ELA classroom: the classroom library.

When I speak to teachers about the diversity in a classroom library, they fall into two camps: ones that have LGBTQ+ books available to students and those that don’t. If you fall into the first camp, the following list is going to help you get started. If you are a person who already has LGBTQ+ books in the classroom, the list is going to help you be more conscious of the types of LGBTQ+ books you’re providing your students.

Let’s get started!

Step #1: Find books that include LGBTQ+ protagonists.

Perform a quick audit of your classroom library. If you were to randomly take 20 books off the shelf, how many of the protagonists would be members of the LGBTQ+ community? Often times, if there is an LGBTQ+ person in a story they are tokenized and used as a sidekick. Each year I commit to buying a certain number of books featuring LGBTQ+ protagonists to add to my classroom library. A diverse library doesn’t happen by accident. You must plan for it. Start researching middle grade and young adult lists that feature LGBTQ+ protagonists, read the synopses, and purchase ones for your students read and enjoy. Revisit these lists regularly for new additions.

#2: Find narratives with LGBTQ+ characters that are plot diverse, not just ones about LGBTQ+ trauma.

There are so many stories to be shared in the LGBTQ+ community. Stocking bookshelves with one type of narrative does not support LGBTQ+ students and non-LGBTQ+ students who are looking to learn about the experiences of the LGBTQ+ community. Traditionally, stories of LGBTQ+ young adults are ones where they struggle to be their authentic selves, fear lack of acceptance of family and friends, and struggle with finding where they belong in the world. These are often stories of physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual trauma.

While having some of these stories are important, having them be the only story shared on your shelves is dangerous as children come to attempt to understand who they are. LGBTQ+ protagonists deserve to fall in love, play sports, save the world, have loving families, etc. When doing your research of books featuring LGBTQ+ characters, find stories that will fill the hearts of LGBTQ+ readers and bring smiles to their faces.

#3: Find LGBTQ+ characters across all genres.

LGBTQ+ characters should be able to see this part of their identity across all genres.

They should be in faraway galaxies saving the universe.

They should be trying escape the ghosts in a haunted house.

They should be traveling back into time to keep the timeline intact.

They should have magical powers that are yielded to defeat villains.

They should be falling in love without issues of identity.

They should be helping their best friend win contests.

They should be on the courts or fields sinking the winning basket or throwing the game-winning touchdown.

They should be solving the mystery of who stole their best friend’s bike.

LGBTQ+ students should see their interests mirrored through the books we offer them in our classrooms and non-LGBTQ+ students should see LGBTQ+ characters normalized being present across genres.

#4: Find books that share the stories of all the letters of the LGBTQ+ community.

If you look at what LGBTQ+ middle grade and young adult literature is readily available for purchase, the narratives heavily center stories of young, cisgender gay males. Teachers need to offer these stories; however, they should deliberately seek out stories that share the experiences of young people who identify as queer, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, non-binary, gender fluid, intersex, asexual, and questioning too. Every reader deserves to see themselves in a piece of literature.

#5: Find books that share the stories of intersecting identities.

Not only does middle grade and young adult literature center the young, cisgender gay male experience, but it also centers the Christian, white experience. It is so important for students to see that LGBTQ+ experiences span religion and skin colors. A young person can be a lesbian Muslim. A young person can be a non-binary Black person. A young person can be Asian and trans. An Indigenous person can be a bisexual young person. Teachers should seek out these middle grade and young adult stories which share the intersection of these identities. There’s no one LGBTQ+ story or experience. The more stories and experiences that can be shared, the better for all the student in the classroom.

Bonus Step (but an important one): Find books that don’t reinforce the binary/limits of gender or gender expression.

In middle and high school as students seek to explore what it means to be a young person; students often retreat into the strict ideas of girl and boy or masculine and feminine. For people who do not fall into this either or, it can be difficult to feel a sense of belonging. Find stories that feature protagonists that do not fall into these stereotypical/traditional behaviors of masculine and feminine. Find that protagonist that is unabashedly themselves in whatever gender expression they may exhibit who are leading awesome lives and kicking butt.

Building a classroom library that includes inclusive LGBTQ+ narratives will take time; however, these steps will get you started! If you are looking for a place to get started, check out the following link which has a variety of LGBTQ+ middle grade and YA stories for you to consider adding to your ELA classroom shelves.

Ready for the next step?

Click over here to read John’s next blog post that shows you HOW to get all of the great new books in your library actually into the hands of students that need to and want to read them…

Check out some LGBTQ+ books to add to your classroom library.

The following are affiliate links from which the author will earn a small commission from your purchase

LGBTQ+ Children's Books: https://a.co/1HIU1lm

LGBTQ+ Middle Grade Books: https://a.co/geHRTkV

LGBTQ+ Young Adult Books: https://a.co/4GeELKK

MEET OUR GUEST CONTRIBUTOR:

John Rodney has been a secondary English educator for the past 15 years at both the middle and high school levels in Southern California. For inclusive practices, relatable experiences, classroom tips, and good laughs follow him on Instagram at @teachertoteacher, TikTok at @teachertoteacher, and Twitter at john_j_rodney. He would love to connect with you.

5 Tips for Creating and Implementing a Successful Unit Plan in Secondary ELA

Unit planning can feel overwhelming, but this guest post provides practical, easy steps for getting started on any unit. Follow Samantha’s guidance as she demonstrates the ways in which she organizes her “The Crucible” unit here!

5 Tips for Creating and Implementing a Successful Unit Plan in Secondary ELA

The following post is a guest writer contribution from Samantha in Secondary.

Creating a successful unit plan in secondary English Language Arts can be a daunting task. How should you get started? How do you know what students should be learning? How can you tell that they’ve actually learned something? In this blog, I’ll give you 5 tips for creating your unit plan that will help you consider the way you think about the unit all the way through assessing students’ learning.

#1: Getting Started with Unit Planning

In order to create a successful unit in ELA, you have to first know what’s expected of you. Does your district require that specific texts be taught? How about certain standards? Expectations vary widely from district to district, so make sure you know what’s expected first before you begin your planning. For example, my district requires that all 11th graders read “The Crucible” by Arthur Miller, so I knew that I was going to need to teach it.

#2: Begin with the End in Mind

Now that you know what’s expected of you, think about what you want students to understand when they’ve completed the unit. Having a clear goal will help you stay on track. This can sometimes come from the standards or can even be the response to whichever unit frame you’ve chosen. (See the next step!) Getting really clear on the unit goal will help your unit run much more smoothly. With my unit on “The Crucible”, I knew I wanted students to see how literature can translate to real life and span generations. “The Crucible” is an enduring text with plenty of implications in our current society, so I wanted them to be able to see that.

#3: Figure Out the Frame