Three Myths about Close Reading

Three Myths about Close Reading (Busted!)

Wait, what? Close reading? That thing in Common Core everyone says they do but can never actually explain? If these sound like your thoughts, you’re not alone. And here’s why:

Close reading is often confused or made synonymous with things it most definitely is not, making it seem too scary to even approach. Maybe you’ve tried it, hit a wall of frustration, and abandoned-ship.

Well, it’s time to replace frustration, uncertainty and fear with the truth, and bust three common myths of close reading.

Three offenders.

Three stories that have run amok doing what myths do best – attempt to explain what we don’t understand.

But the thing is, close reading CAN be explained and understood, and there is a close reading reality. Let's talk THAT reality, so you can see the power this instructional strategy has to transform both your teaching of reading and your students’ growth and confidence.

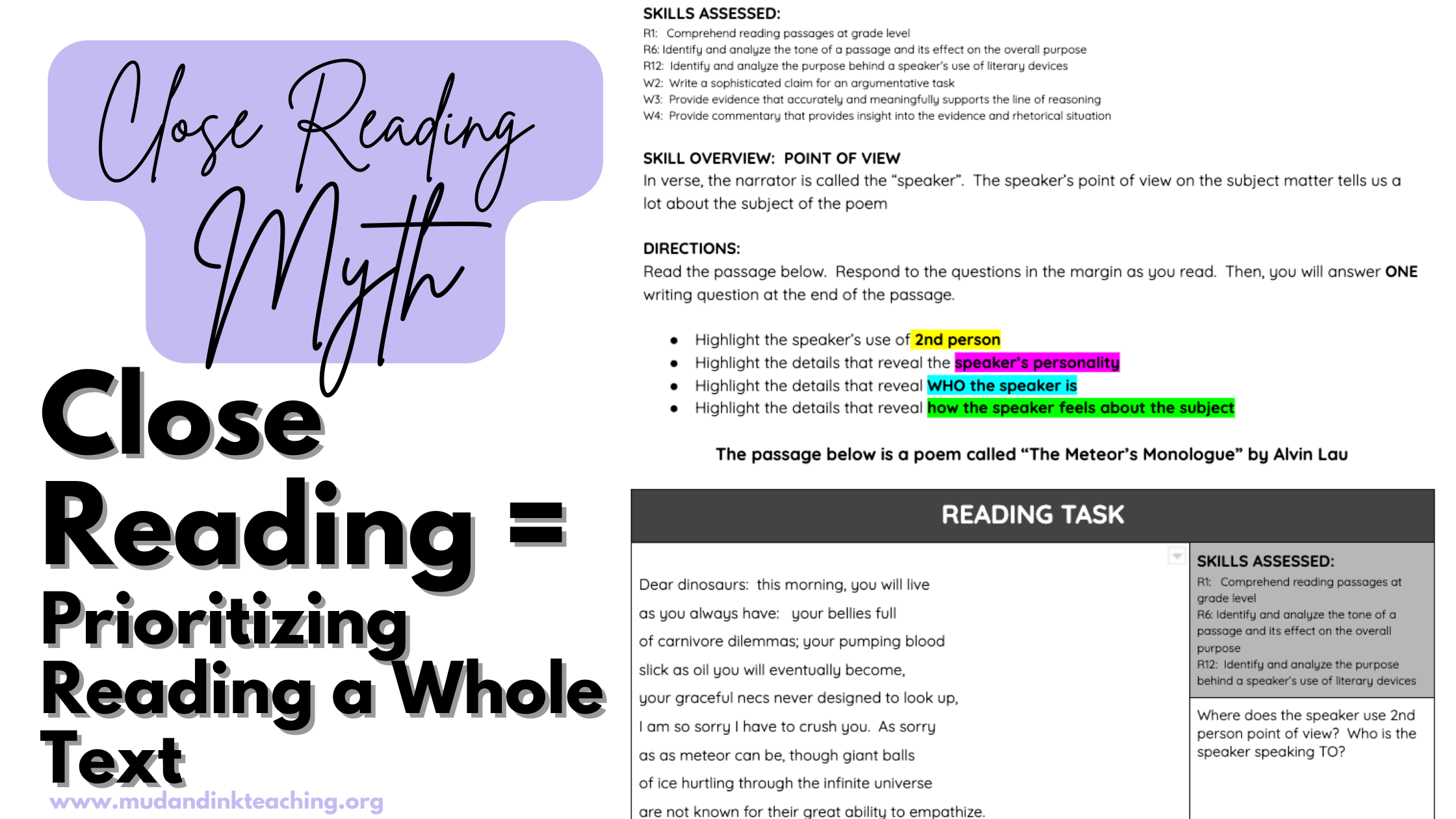

MYTH #1: Close Reading = Reading an Entire Text

If the thought of figuring out how to teach a close read of an entire short story, or

an entire chapter OR

an entire article OR

an entire scene

gives you hives, well, that’s fair. It should!

If telling your classes to “do” a close read of X story results eye rolls, audible groans, and no sense of whether students are actually practicing reading skills – also fair.

This idea that close reading means scrutinizing an ENTIRE text is a complete and total, well, MYTH! It is also a recipe for overwhelm for both teachers and students, with little to no benefit for students’ growth as readers. Reading an entire text is just that – reading. And while there is nothing wrong with “just reading” that is not the purpose of close reading.

HERE’S THE REALITY: Close Reading = Reading a Passage

Close reading is re-reading with intention, with the purpose of practicing skills, learning patterns and deepening understanding. So instead of an entire text, choose passages no more than a page long, maybe going onto the back, for your lessons.

Begin by having students read a longer chunk: a chapter or chapters, an act, a short story – either for homework or independently during class – of which the passage is part. When the kids come to the close reading lesson, it will be at least their second encounter with said passage.

Pffft, you might be saying. My students aren’t going to read that longer chunk independently.

That might be true. But they can still do the lesson.

Close reading lessons are always in-class, skill-focused, teacher-directed experiences. Keeping the passage short allows students to do the lesson whether or not they completed all of the prior reading. The passage is read, and often re-read, in class, so you know, at the very least, even if students read nothing else for an entire unit, they have read those close reading passages and practiced skills.

Length is critical, and to keep passages short, it is not only ok but necessary to eliminate content that does not help students practice the skill. Consider what is most important and what is necessary for student practice. Then decide how much to include before and after. Context can always be provided by you for the kids in the lesson directions.

MYTH #2: Close Reading Prioritizes Reading the Whole Text

Your reading curriculum contains four core novels and a Shakespearean play. The best way for students to grow as readers, writers, and thinkers is to make the text central to learning. They must read every page and every word of every novel and the play in order to make progress. Frequent comprehension quizzes are the way to keep them accountable.

Close reading is reading EVERYTHING – page one to page end.

Um, no. Just NO. To ALL of that.

HERE’S THE REALITY: Close Reading Prioritizes Skills

Close reading DOES NOT – like, to infinity DOES NOT – center the text.

Close reading centers SKILLS.

The text is the vehicle through which skills are taught. Don’t get me wrong, the text is important, but students are not being assessed on whether or not they “know” the whole text. They will be assessed on the skills you taught and that they practiced during your close reading lessons.

Skills can run the gamut – from rhetorical situation to recurring symbols, to use of imagery – depending on the type of text, your essential question (more info on this here), and your summative assessment. The skills determine the annotation focus(es). Remember, though, not to get carried away in asking students to annotate for all the things. Less is more.

Make it super clear in your directions what you want them to annotate for. Without this, students end up randomly highlighting and labeling with no sense of how or why it all fits together. Instead of wild goose chase annotation, send students on a purposeful, scaffolded path toward analysis.

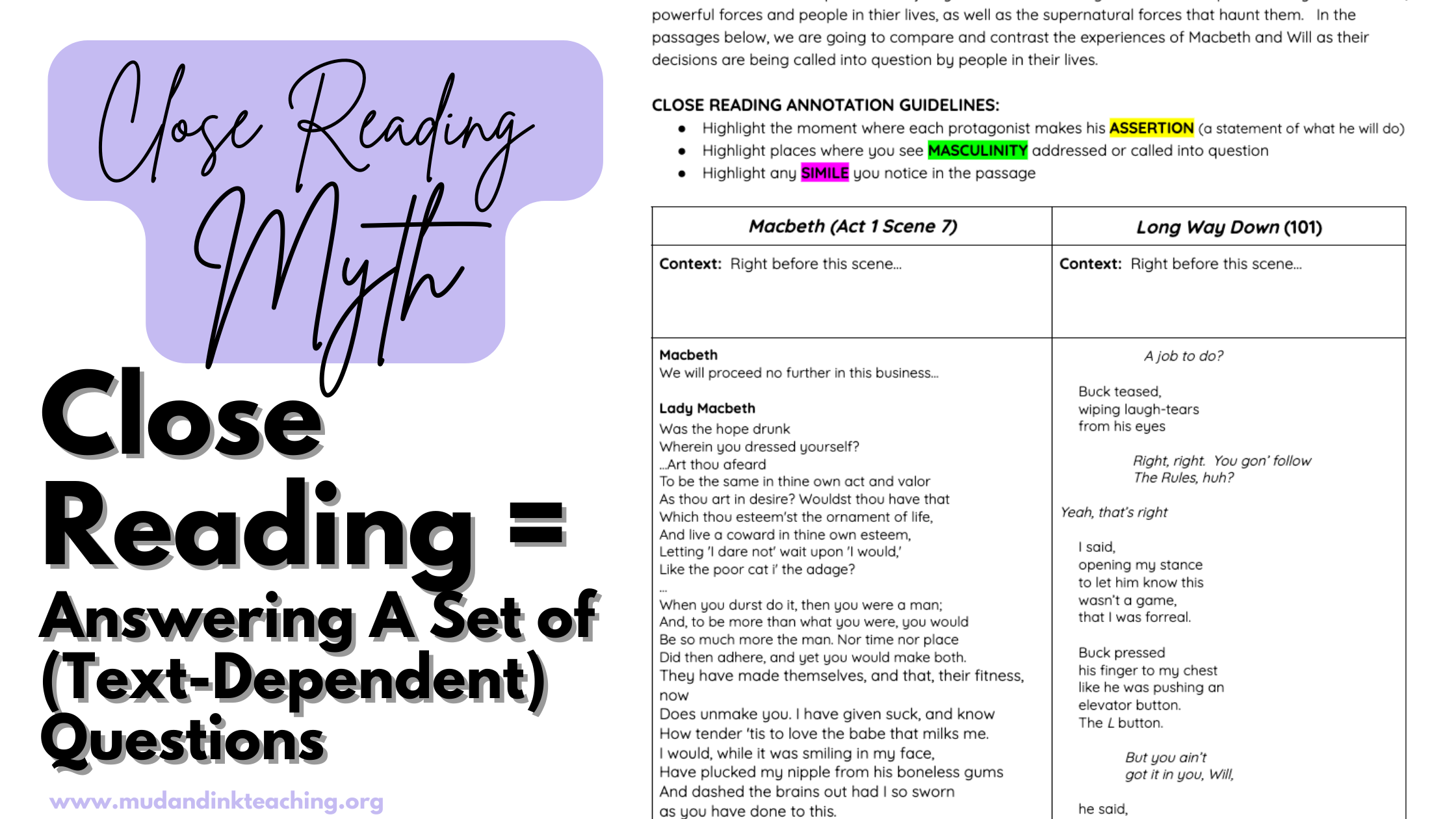

MYTH #3: Close Reading Answers A Set of (Text-Dependent) Questions

You are at the photocopier and find a handout titled, “Close Reading Questions.” You look through it and consider that maybe this is close reading.

Nope. Not even kind of.

HERE’S THE REALITY: Close Reading Works with Essential & Analysis Questions

A list of teacher-created questions for students to answer as they read a text – or after they read it – could maybe be considered “guided” reading. But it is not close reading.

Close reading does involve questions, but they are of the essential and analytical variety. And you come up with them before students close read anything. These are the questions that drive your unit and skill focus. They are the questions that inform your backwards planning: what it is you want students to know or do by the end of that unit?

Your close reading lesson passages should all connect to your unit essential question (more on EQs here), so that they build on each other, which results in students building their learning – comprehension, pattern recognition, deep thinking – over time.

And within each lesson, you create an analysis question for students to work with at the end. When planning a close reading lesson, come up with this question first. Consider what you would look for in the passage to answer it. This will help you come up with student annotation guidelines. Having kids draft a skills-focused analytical paragraph to answer a question using their close reading annotations helps prepare them not only for a summative task, but makes them derive meaning, instead of searching for a “correct” answer.

So, yes, questions, BUT questions that require students to make meaning using the skills they practiced in that close reading lesson for that particular passage, not to hunt and peck through an entire text to find “the answer.”

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS…

Close reading is not its mythology! It is not reading an entire text, it is not whole-text centered or answering a set of text-dependent questions. Close reading reality decenters the text, prioritizes skills, and uses essential and analysis questions to drive learning. This instructional strategy has the potential to move mountains for your students as readers, writers and thinkers and for YOU as a teacher of reading.

If you haven’t tried close reading before in your classroom or if you’d like to revisit it after a less than positive experience, grab this free video where I go into more depth about the what, why and how of close reading. What has been your experience with close reading? What questions do you have?