ADVENTUROUS TEACHING STARTS HERE.

20 Speeches and Text for Introducing SPACE CAT and Rhetorical Analysis

During the introductory phases of teaching rhetorical analysis, you need to start off with texts that are approachable and teachable. This helps to build student confidence as the texts get harder and harder each year. Here are 20 places where you can start that journey confidently!

When it comes to introducing rhetorical analysis for the first time, choosing texts can feel like an intimidating task. But before you get bogged down with which text to pick, let’s talk through a few initial steps to help ensure your success.

TIP #1: Begin with a Framework

When I first was told to “teach rhetoric”, I had virtually no training or support. I resorted to what I knew from my undergrad: an overview powerpoint about ethos, pathos, and logos. This is exactly the path that I would actively AVOID if at all possible (I’ve written about that more here), and instead begin by introducing students to the framework that you’ll use in order to do the work of analysis. For me, I’ve found SPACE CAT to be my favorite ( BTW, I also do this with poetry using The Big 6).

TIP #2: SKIP ETHOS, PATHOS, LOGOS IN YOUR INTRO

Okay — hear me out. I’m not saying don’t teach ethos, pathos, or logos. I’m saying don’t use that as an INTRODUCTION to rhetoric.

Here’s why:

Whatever the first thing is that students learn is going to be the thing that they think is the most important. And to be perfectly honest — the appeals alone are NOT the most important part of rhetorical analysis.

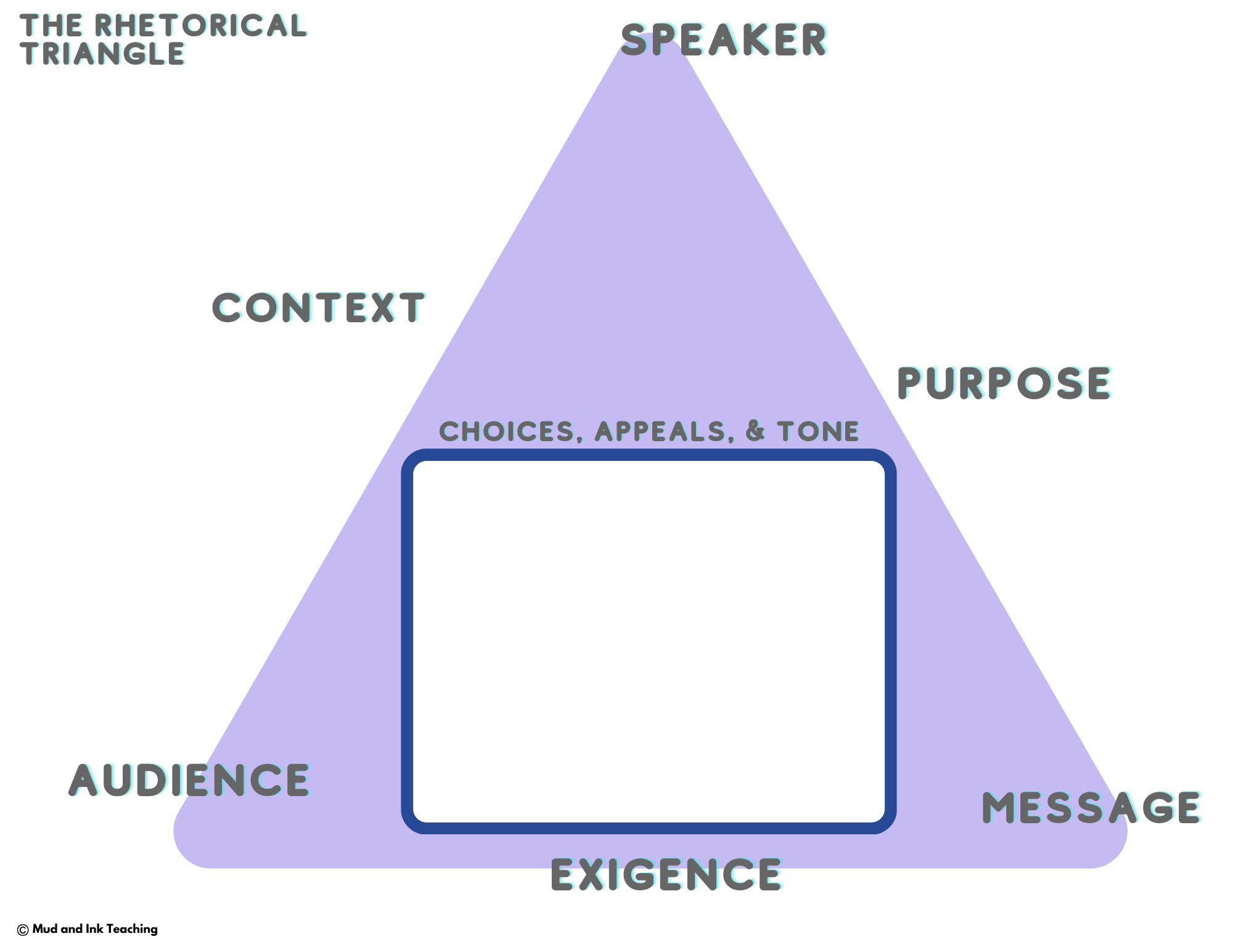

So what to do instead? Introduce the RHETORICAL TRIANGLE.

The Rhetorical Triangle sets students up to see the ways in which an argument moves from one person to another. It centers students on their role as analysts and the need to be inside of the argument - not outside attacking it with a highlighter.

For two more in-depth discussions and lesson examples on the rhetorical triangle, start here:

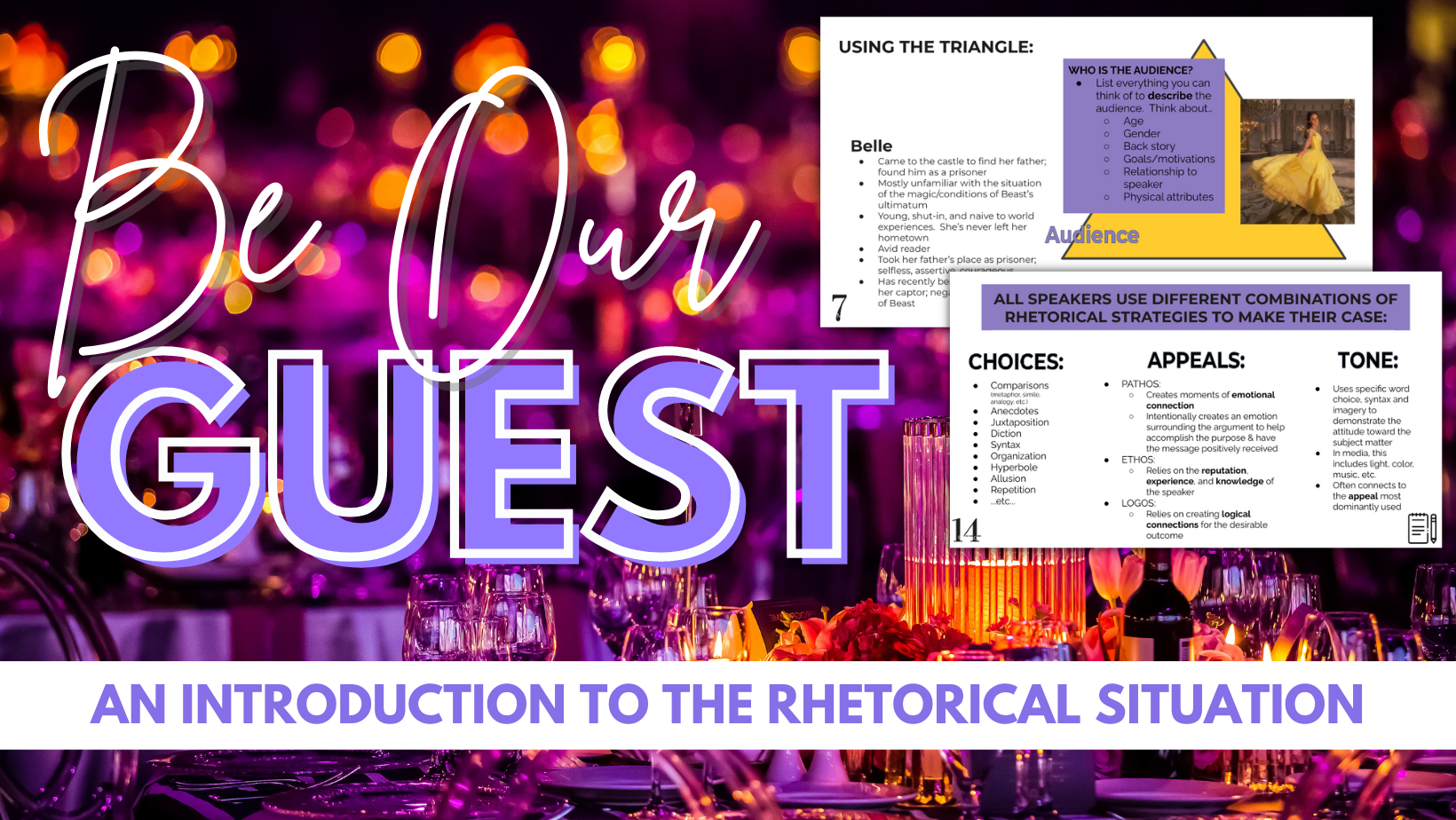

“Be Our Guest” from Disney’s Beauty and the Beast

“Mother Knows Best” from Disney’s Tangled

TIP #3: TEACH ON REPEAT

If you’ve not started “template teaching” let me encourage you to make this the day that you start. As you browse through the list below, try to think of these texts as opportunities to teach and reteach the same skills over and over — not a daunting list of individual lesson plans.

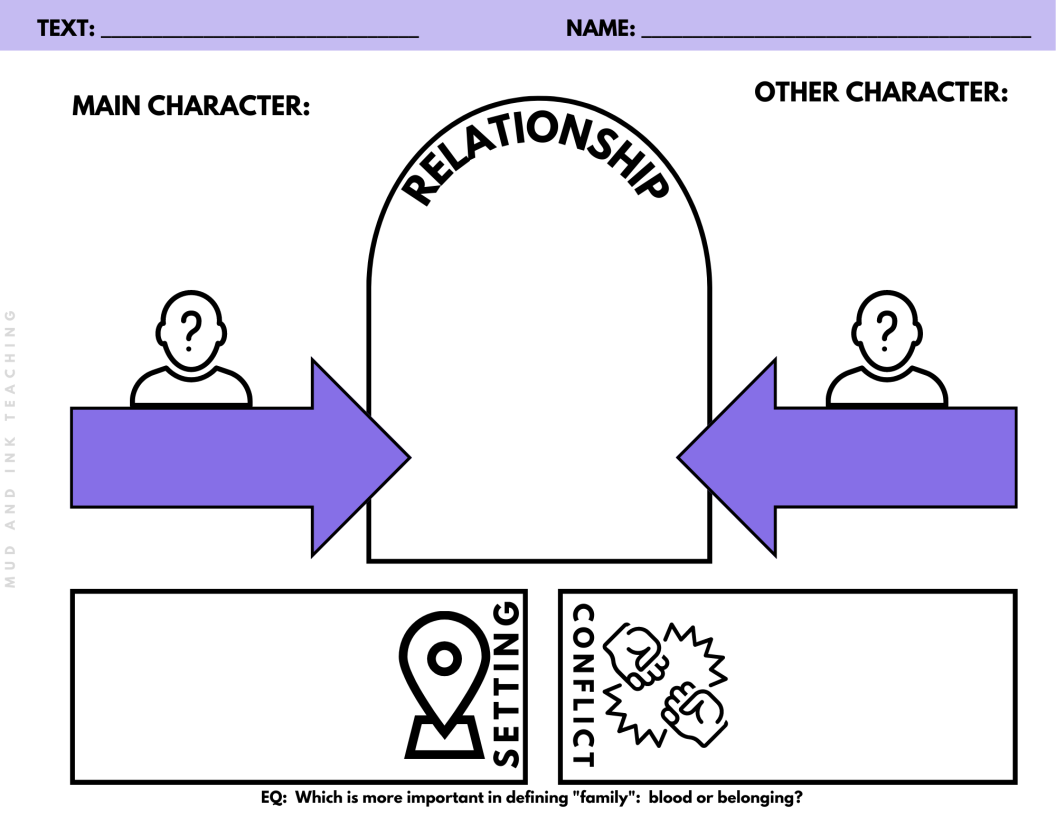

Begin by introducing the rhetorical triangle and situation using either of the two lessons listed above. During those lessons, introduce students to the rhetorical triangle graphic organizer template and help them become well acquainted. This graphic organizer will be the TEMPLATE to print and repeat for every lesson hereafter.

Once students are ready to move to more challenging texts, start movin’. What’s the lesson? It’s all baked in to your graphic organizer template. Using just that one handout, students can do a huge variety of tasks all with varying levels of challenge and independence. Here are a few ideas:

In small groups, bullet point details about the speaker. SHUFFLE GROUPS, and in the new group, bullet point details about the audience, SHUFFLE GROUPS, and in the new group bullet point details about the context. Repeat as needed for each element of SPACE.

Read/watch the text together. Complete S - P - A together and assign C - E to work on in pairs

Put students in small groups. Designate areas/tables around your room as S, P, A, C, and E. Have students move through each station with their group and their handout to analyze the text.

Have students choose any text from a provided list and complete the graphic organizer independently for homework / individual work

This template allows you to flex the details of your lesson without having to prep brand new handouts for every single new text!

THE LIST YOU’VE BEEN WAITING FOR: THE BEST TEXTS FOR INTRODUCING SPACE CAT

This list comes both from personal experience and teacher recommendations. If you have experience or more ideas, please feel free to add them to the comments at the end of this post!

“The Other Side” from The Greatest Showman

Battle speeches from Queen Magra and Baba Voss from the Apple TV Series See

“Be Prepared” from Disney’s The Lion King

“I’ll Make a Man Out of You” from Disney’s Mulan

“Under the Sea” from Disney’s The Little Mermaid

“How to Mark a Book” by Mortimer Adler

“Farewell to Baseball” Lou Gherig

Challenger Speech from Ronald Reagan (and grab my close reading template for this speech here)

9/11 Address from George W. Bush

“Offensive Play” by Malcolm Gladwell

Back to School Commercials

What would you add to this list? I’d love to hear it in the comments below!

Happy teaching!

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS RESOURCES

Four Review Games & Activities for the AP Lang Exam

Tackle the AP Language and Composition exam with confidence using any of these four classroom-tested review strategies. This list will give you plenty of ways to prepare for the exam while having fun and working hard to get students as ready as possible for test day.

Test prep is a mixed bag of emotions for me. Teaching to any test is a quick trigger of my fury, but after time and experience with the AP Language and Composition exam, I’ve really shifted my mindset. In many ways, the entire course is test prep. The course is backwards designed: exam at the end, curriculum built from back to front to support the skills needed to perform on said exam. But what’s different about the Lang exam than any other test I’ve ever experienced in the secondary education world is that I care about these skills.

Are the timing constraints, blind prompts, and other testing factors perfect? Not by a long-shot, but time after time, I’ve seen my students flourish as writers over the course of a year as they prioritize the skills that show up on the exam.

So here’s the thing: we don’t talk much about the exam during the year. Yes, we do some timed writes, but those are for me to measure progress and less about “prepping” for the exam. But when it gets closer to exam time, we do start to talk more about the components of the exam and discuss the different ways students would benefit from reviewing the coursework and practicing the skills before test day.

These are four of my favorite review activities that I wanted to pass along. I hope you find a few gems here and can take a bit of the workload off your shoulders this May!

Choice BoardS

Not every student needs to work on the same things, and this is where a choice board comes in so incredibly handy. With a choice board, you can create categories of review study and load each category up with options that will review, give practice, or challenge students as they prepare for the exam. I design my choice boards in either Google Slides or Canva. In Slides, I build the board using VIEW —>. TEMPLATE, basically building out the “background” of the slide. Then, I add buttons on top of that background that are clickable and linked to various review materials. In Canva, I make the board, link each box, and then share a VIEW ONLY link with students. It makes no difference at all what you use — it’s all up to your comfort level. I have one made and ready to share if you want to take a peek and see if what I have will work for your students, too.

2. Mother Knows Best (Disney)

When it comes to reviewing for RA, there’s nothing more that I love than using some Disney. Disney songs (and so many other songs in musicals) are plot based, therefore, the characters that are singing often have an agenda of some sort. Take Mother Godel, for instance. After kidnapping the princess to take advantage of her magical hair, Mother Godel has a lot invested in this tower situation. It’s imperative that she keep Rapunzel in that tower locked away, so when Rapunzel starts to get a bit curious and ask questions, Mother Godel shuts down that show pretty darn fast. Using Disney songs and movies are a playful way to review RA skills, and at this time of the year should be pretty easy for students to dive into in small groups without teacher assistance. I also use these to introuce rhetoric, but a Mother Godel lesson in October is a very different from one in May. Use it how it best suits you!

3. Commencement Speeches

There are many benefits to using commencement speeches for exam review:

They fit into the end of the year feel and thematically feel like a natural fit this time of year

Commencement addresses are frequently used on FRQs if you check out past exams

There are plenty of engaging, interesting speakers to choose from all across YouTube

Depending on the speech, you might need to amend the length, but other than that, these speeches are abundant and easy to find. I like to take these speeches and break them up into pieces and make small groups experts on each piece. We then bring the pieces together for a “work as a whole” conversation and that is usually very powerful in preparation for exam day.

A few more speeches I love using:

4. Spare Change Game Show

If you’re looking for a whole class, interactive, hysterical and fun way to practice argument, The Spare Change Gameshow is it. All you need is a coin to flip and a timer! Using my slide deck, students are paired up and face off arguing for and against a wide set of claims. My favorite part of this exercise is that the coin decides the students’ argumentative fate: heads must argue the affirmative, and tails must argue the negative. It makes no difference whether or not they actually agree or disagree with the claim: they must comply with their coin’s decision.

So there you have it, folks. My four favorite ways of exam prep before the AP Lang Exam. I hope one of these resonated with you and that you have a wonderful end of your school year with students. Let me know in the comments how you’re feeling this year and which of these review materials you plan on using!

LET’S GO SHOPPING

Teaching Rhetorical Analysis: Using Film Clips and Songs to Get Started with SPACE CAT

Try beginning your rhetorical analysis lessons by focusing on the rhetorical situation before heading into deeper analysis. When you’re ready, dig in using SPACE CAT and a great song from a musical that has a premise and an argument to examine. Here’s what we’ve done in my class using “Mother Knows Best” from Tangled.

Rhetorical analysis: so much more than commercials and appeals

Rhetorical analysis can get a stuffy reputation. Sometimes, we reserve it only for “serious” classes and students and we focus on monumental, world-shaking types of speeches. While this approach accomplishes a few of our long-term goals for education, it’s not doing enough to reach the masses of students who need these skills.

I hope you’re here reading this because you want to try RA with seventh graders. You want to introduce rhetorical analysis to your struggling 10th graders. I hope you’re here because you’re trying to do RA even though you haven’t been deemed worthy and been exclusively anointed as an AP Lang teacher. I hope you’re an AP Lang teacher here looking to do things with a broader scope and new entryways into conversations about complexity and sophistication.

Really, I’m glad you’re here.

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: THE BASICS

Here’s where we need to start: the triangle.

Rhetorical analysis is less about appeals and more about the unique connection between three points: the speaker, the audience, and the message.

When we start RA zeroing in on ethos, pathos, and logos, we are playing a bit of a dangerous game. Teaching terms can be a comfort zone for teachers (we do this with figurative language, too). In our field, there are so few direction instruction content types of lessons, that it can feel cozy to snuggle up with a list of terms we understand and deliver them to our students. Without realizing it, we’ve created a pretty deep hole, jumped in, and forgot to throw down the rope ladder for when we need to get back out.

When we start with terminology, we’re sending the message to students that this is the primary focus of analysis: identification. We’ve armed them with dozens of terms, so the goal of analysis must be to slap these labels all over a speech and call it annotation. Then? It ends. Students falsely believe that they’ve accomplished the task because they did exactly what you taught them. They found the rhetorical questions. They found a simile. They found an example of ethos.

And then? We get really frustrated when they can’t tell us WHY, HOW, or SO WHAT when we probe them deeper about what they’ve identified.

This is my very long way of telling you this: DON’T start with terms, or, if you do, be ready to pivot quickly!

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: WHERE TO BEGIN

START with the rhetorical triangle or a framework that you like (I like SPACE CAT) and a conversation around the rhetorical situation (SPACE). By emphasizing the importance of understanding the components of the broader context of the argument, we help students start the probing question why? in the back of their heads as we go deeper and deeper into the argument itself.

One of my favorite pieces to use for practicing the rhetorical situation is looking at Lumiere’s plea to Belle in “Be Our Guest”. In another blog post, I outline how much there is to the situation -- there is so much to consider in terms of the speaker, the purpose, the audience, the context and the exigence. In the slide deck for this lesson, we spend a great deal of time listing as many details as possible before even looking at a single lyric. Why? Because once we get into the argument, we’re seamlessly moving through true analysis.

Ms. C? I think I found a simile.

What similie is that?

Well it says ____________.

Hmm.. You’re right. So why does this particular simile hold weight knowing what we know about who Lumiere is and what he’s trying to achieve in this moment?

Wheels turning…

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: GETTING INTO THE ARGUMENT

So we’ve got a handle on the rhetorical situation. That’s a win. In fact, that might be the entire goal of a unit if you’re just beginning. If your school is taking their time and truly working on vertical articulation, this is a great skill to introduce at 9th grade and build toward mastery in 10th.

But let’s say we’re moving on a bit and ready to analyze the argument. You might have a speech, a commercial, another song, or another type of fictional scenario, and now we need to look at the techniques used and do the analysis work.

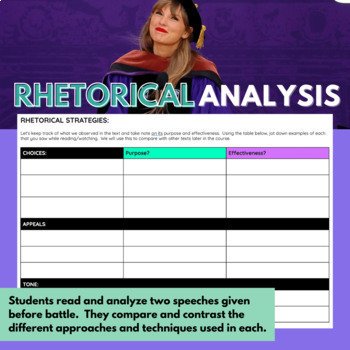

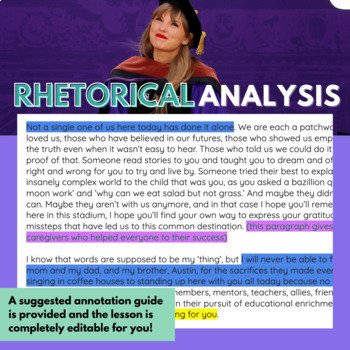

This is where we come back to our analysis framework. I like using SPACE CAT, so this stage is where I rely on CAT: choices, appeals, and tone.

Rhetorical choices include just about everything, so it’s up to you to narrow the lane of what each argument is doing well. A rhetorical choice might be the structure or organization of the argument, an extended metaphor, the use of personification, or even a particularly interesting use of parallel structure. Appeals are what you think they are: ethos, pathos, and logos. And of course, tone is exactly what you think it is, too.

Not all choices, appeals, or potential tone words are important to talk about in every speech, so fully embrace your right to decide ahead of time which choices are on the table for discussion (this is called scaffolding and if you need help with it, I have a training in my Mastering Close Reading Workshop that you might find very helpful!).

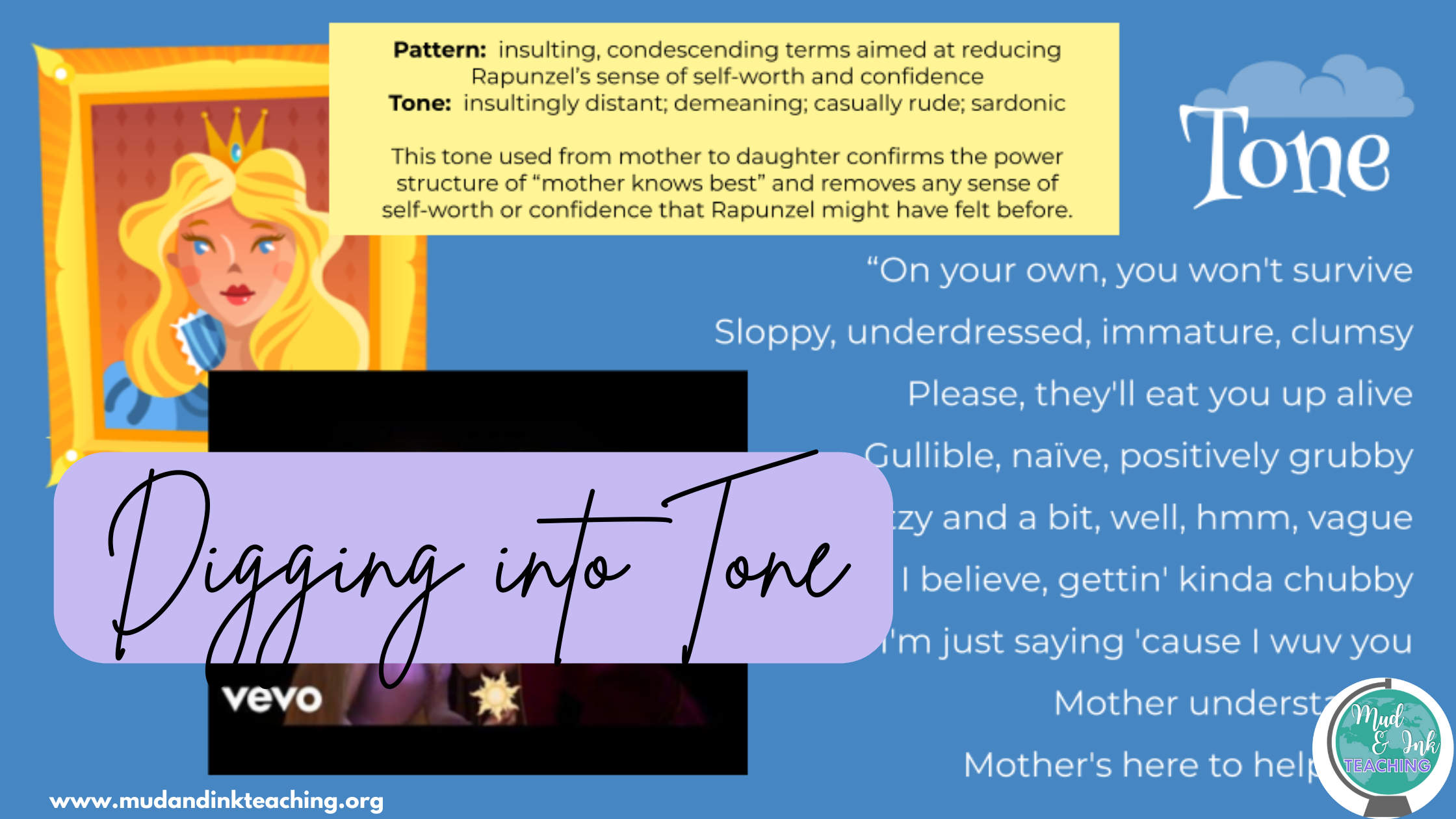

Let’s Look at an Example: “Mother knows best”

Here’s a quick example from “Mother Knows Best” in Disney’s Tangled for each of the components in CAT.

Mother Godel opens her song referring to Rapunzel “as fragile as a flower; still a little sapling, just a sprout”. She’s comparing Rapunzel to an undeveloped, extremely young plant.

She then uses the refrain “Mother Knows Best” along with other overly-assertive physical behaviors to assert her own ethos and Rapunzel’s lack of life experience.

The song also gives students the chance to look at tone, especially in the verse where Mother Godel tells Rapunzel that she won’t survive as a “sloppy, underdressed, immature, clumsy” and “gettin’ kinda chubby” girl out in the real world. This demeaning tone further underscores Mother Godel’s authority and increases the fear in Rapunzel about leaving her tower.

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: SO WHAT?

Well, we’ve arrived back where we started, friends. There’s a whole lot of highlighting, lots of phrases and details identified as one thing or another, but here comes the real work: SO WHAT?

So, Mother Godel uses a demeaning tone toward Rapunzel. So what?

She compares her to a “sapling” that has just sprouted from the ground. So what?

Here’s where we send students back to the rhetorical situation.

Support them through their “so what” with questions referring back to SPACE:

Why is this tone effective given what we know about the audience?

How does this metaphor create a sense of fear in Rapunzel?

How does Mother Godel’s use of hyperbole help her achieve her purpose?

Given the context of the situation, why would Mother Godel rely on the emotion of fear in this particular argument?

Once you’ve gotten through the SPACE, the CAT, and now arrived at the analysis part, remember that you can do this a few ways. Students oftentimes will write a paragraph of analysis, but if you’d prefer, you might have students complete a one-pager or just have a discussion that outlines what students could write about. It’s okay for some lessons to be heavier on the process than on the result.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS…

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: TRUST THE PROCESS

This is the process. It takes time, practice, and more practice. But if you are able to confidently lean on a framework that you like, provide the right types of arguments that meet students where they’re at, and stretch their work with rhetoric over multiple years, you’re going to find increasing success.

If you’re looking for more support, I have resources that are ready to help you. Keep doing the work -- I’m right here behind you every step of the way.

LET’S GO SHOPPING…

Three Myths about Close Reading

Close reading is often confused or made synonymous with things it most definitely is not, making it seem too scary to even approach. Maybe you’ve tried it, hit a wall of frustration and abandoned-ship. Well, it’s time to replace frustration, uncertainty and fear with the truth, and bust three common myths of close reading.

Three Myths about Close Reading (Busted!)

Wait, what? Close reading? That thing in Common Core everyone says they do but can never actually explain? If these sound like your thoughts, you’re not alone. And here’s why:

Close reading is often confused or made synonymous with things it most definitely is not, making it seem too scary to even approach. Maybe you’ve tried it, hit a wall of frustration, and abandoned-ship.

Well, it’s time to replace frustration, uncertainty and fear with the truth, and bust three common myths of close reading.

Three offenders.

Three stories that have run amok doing what myths do best – attempt to explain what we don’t understand.

But the thing is, close reading CAN be explained and understood, and there is a close reading reality. Let's talk THAT reality, so you can see the power this instructional strategy has to transform both your teaching of reading and your students’ growth and confidence.

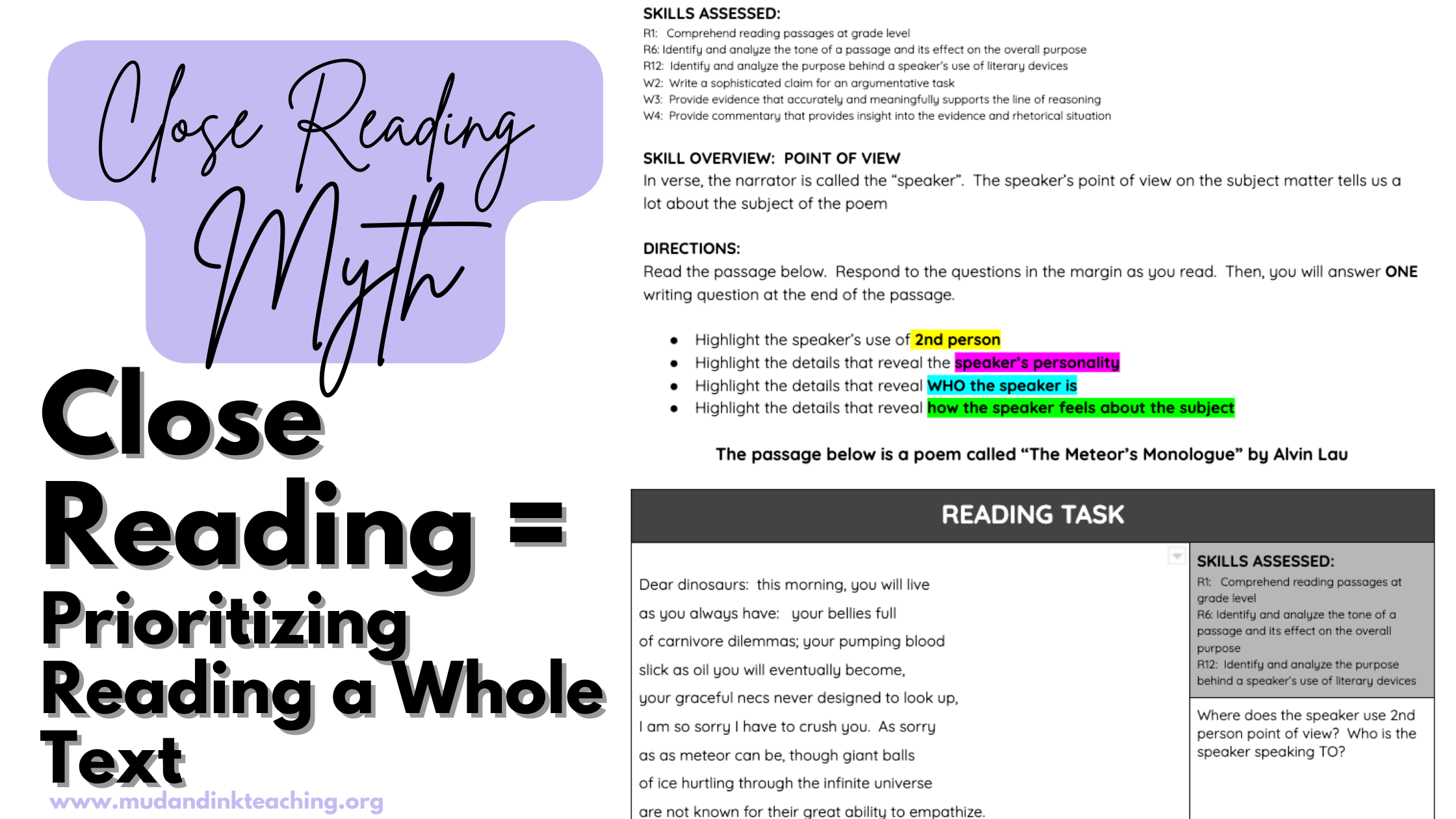

MYTH #1: Close Reading = Reading an Entire Text

If the thought of figuring out how to teach a close read of an entire short story, or

an entire chapter OR

an entire article OR

an entire scene

gives you hives, well, that’s fair. It should!

If telling your classes to “do” a close read of X story results eye rolls, audible groans, and no sense of whether students are actually practicing reading skills – also fair.

This idea that close reading means scrutinizing an ENTIRE text is a complete and total, well, MYTH! It is also a recipe for overwhelm for both teachers and students, with little to no benefit for students’ growth as readers. Reading an entire text is just that – reading. And while there is nothing wrong with “just reading” that is not the purpose of close reading.

HERE’S THE REALITY: Close Reading = Reading a Passage

Close reading is re-reading with intention, with the purpose of practicing skills, learning patterns and deepening understanding. So instead of an entire text, choose passages no more than a page long, maybe going onto the back, for your lessons.

Begin by having students read a longer chunk: a chapter or chapters, an act, a short story – either for homework or independently during class – of which the passage is part. When the kids come to the close reading lesson, it will be at least their second encounter with said passage.

Pffft, you might be saying. My students aren’t going to read that longer chunk independently.

That might be true. But they can still do the lesson.

Close reading lessons are always in-class, skill-focused, teacher-directed experiences. Keeping the passage short allows students to do the lesson whether or not they completed all of the prior reading. The passage is read, and often re-read, in class, so you know, at the very least, even if students read nothing else for an entire unit, they have read those close reading passages and practiced skills.

Length is critical, and to keep passages short, it is not only ok but necessary to eliminate content that does not help students practice the skill. Consider what is most important and what is necessary for student practice. Then decide how much to include before and after. Context can always be provided by you for the kids in the lesson directions.

MYTH #2: Close Reading Prioritizes Reading the Whole Text

Your reading curriculum contains four core novels and a Shakespearean play. The best way for students to grow as readers, writers, and thinkers is to make the text central to learning. They must read every page and every word of every novel and the play in order to make progress. Frequent comprehension quizzes are the way to keep them accountable.

Close reading is reading EVERYTHING – page one to page end.

Um, no. Just NO. To ALL of that.

HERE’S THE REALITY: Close Reading Prioritizes Skills

Close reading DOES NOT – like, to infinity DOES NOT – center the text.

Close reading centers SKILLS.

The text is the vehicle through which skills are taught. Don’t get me wrong, the text is important, but students are not being assessed on whether or not they “know” the whole text. They will be assessed on the skills you taught and that they practiced during your close reading lessons.

Skills can run the gamut – from rhetorical situation to recurring symbols, to use of imagery – depending on the type of text, your essential question (more info on this here), and your summative assessment. The skills determine the annotation focus(es). Remember, though, not to get carried away in asking students to annotate for all the things. Less is more.

Make it super clear in your directions what you want them to annotate for. Without this, students end up randomly highlighting and labeling with no sense of how or why it all fits together. Instead of wild goose chase annotation, send students on a purposeful, scaffolded path toward analysis.

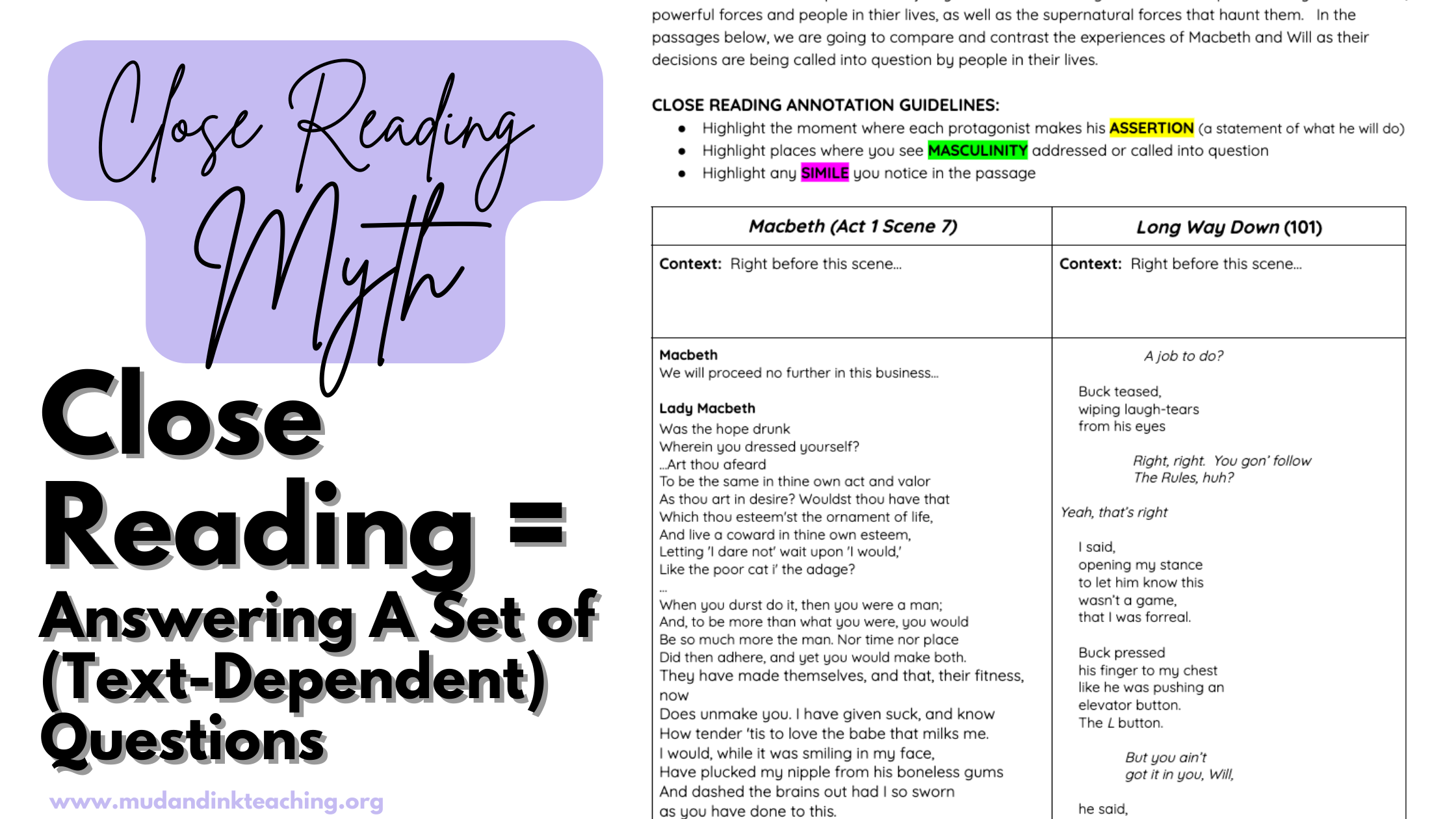

MYTH #3: Close Reading Answers A Set of (Text-Dependent) Questions

You are at the photocopier and find a handout titled, “Close Reading Questions.” You look through it and consider that maybe this is close reading.

Nope. Not even kind of.

HERE’S THE REALITY: Close Reading Works with Essential & Analysis Questions

A list of teacher-created questions for students to answer as they read a text – or after they read it – could maybe be considered “guided” reading. But it is not close reading.

Close reading does involve questions, but they are of the essential and analytical variety. And you come up with them before students close read anything. These are the questions that drive your unit and skill focus. They are the questions that inform your backwards planning: what it is you want students to know or do by the end of that unit?

Your close reading lesson passages should all connect to your unit essential question (more on EQs here), so that they build on each other, which results in students building their learning – comprehension, pattern recognition, deep thinking – over time.

And within each lesson, you create an analysis question for students to work with at the end. When planning a close reading lesson, come up with this question first. Consider what you would look for in the passage to answer it. This will help you come up with student annotation guidelines. Having kids draft a skills-focused analytical paragraph to answer a question using their close reading annotations helps prepare them not only for a summative task, but makes them derive meaning, instead of searching for a “correct” answer.

So, yes, questions, BUT questions that require students to make meaning using the skills they practiced in that close reading lesson for that particular passage, not to hunt and peck through an entire text to find “the answer.”

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS…

Close reading is not its mythology! It is not reading an entire text, it is not whole-text centered or answering a set of text-dependent questions. Close reading reality decenters the text, prioritizes skills, and uses essential and analysis questions to drive learning. This instructional strategy has the potential to move mountains for your students as readers, writers and thinkers and for YOU as a teacher of reading.

If you haven’t tried close reading before in your classroom or if you’d like to revisit it after a less than positive experience, grab this free video where I go into more depth about the what, why and how of close reading. What has been your experience with close reading? What questions do you have?