Class Discussion: When to Stay Quiet, When to Speak Up

Let’s start by taking a quick poll:

Share your answer with us in the comments, and don’t forget to say WHY!

A: Fishbowl / B. Socratic Seminar / C. Philosophical Chairs / D. Online Discussion with Parlay

No matter which of the above is your jam, I think we can all agree that class discussion and the techniques we use to make them happen are all chasing after the goal of helping our students learn to have thoughtful discourse, how to talk about hard topics respectfully, and how to evolve their positions with both concession and deeper, more complex claims.

Discussion, whether it be at the beginning, middle, or after a unit of study, is a cornerstone in the pursuit of an inquiry-driven curriculum. Most often, discussions in my classroom are anchored to the unit essential question and present a series of sub-questions that are related. Students are encouraged to utilize a variety of sources to provide a variety of perspectives on the answer or solution to the question at hand. These discussions are high energy, personal. critical, political, and sometimes even emotional. And we, as educators, need to make sure that all of the pieces are in place so that the conversation can happen organically and without your constant intervention.

Let’s be clear on goals

If I had to make a master list of what I’m aiming for my class discussion to be able to do, it would look something like this:

How to listen to and trace the development of claims and arguments

Building confidence in students owning their own voices

Practice synthesizing information

Build connections between ideas and elevate them to a new layer of the conversation

To learn the difference between neutrality and open-mindedness

To engage in discourse to deepen thought; not to be right or wrong

In order to accomplish these goals, it requires us, the instructors, to set up purposeful scaffolds on the front and back end of each discussion; however, in order for students to engage with the practice needed to meet these goals, we have to let the discussion happen organically and without our interference.

When to Stay Quiet

The simple answer? As much as possible. Your goal is to fade into the background during the discussion and closely observe student interactions and listen to the evolution of the conversation as it unravels organically.

Troubleshooting in the Background

The logistics of these discussion strategies can be difficult to navigate the first few times though, so I’ve built two helpful tools that help me keep track of the discussion quickly and efficiently so I can spend more time paying attention to the content of the conversation.

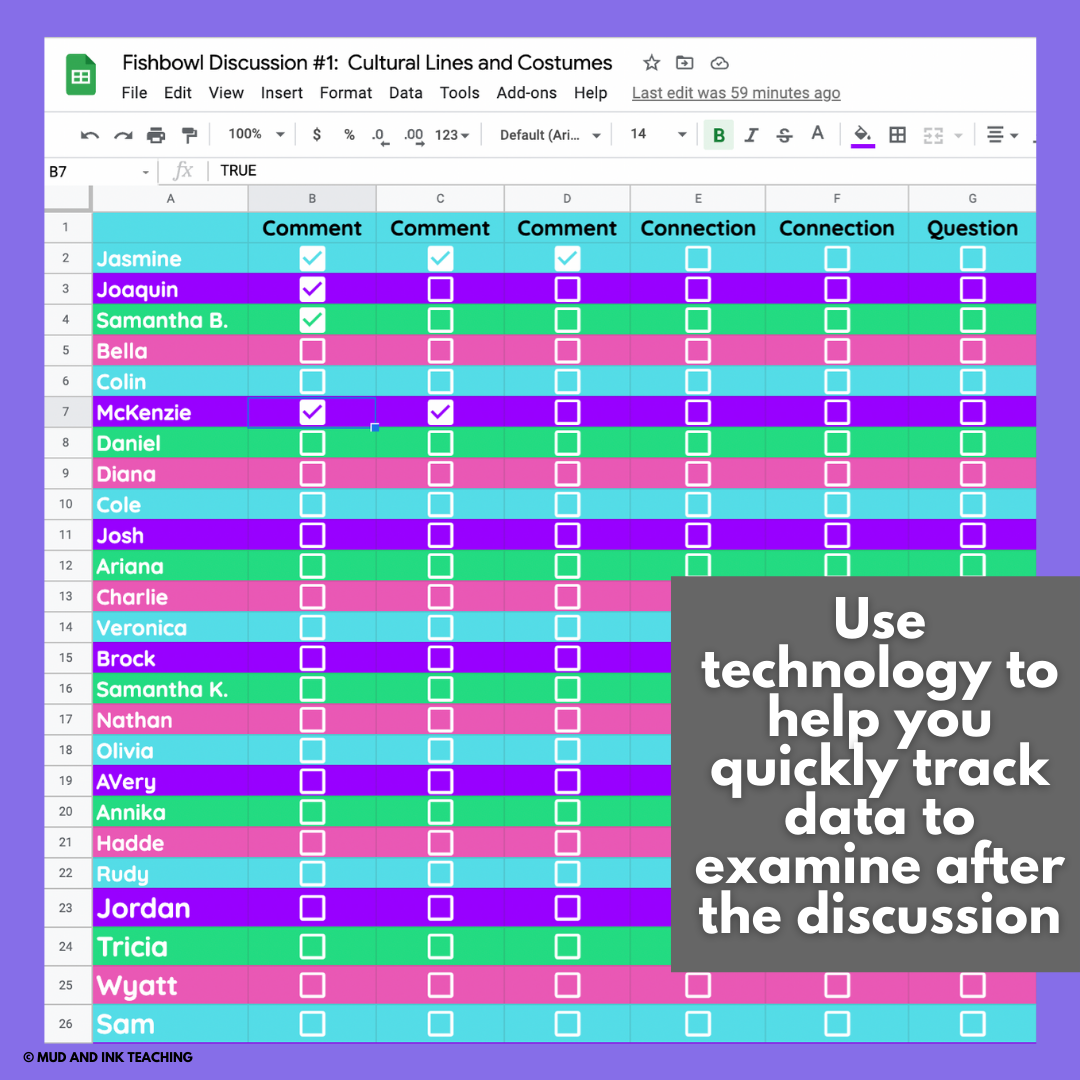

Google Sheets Checkbox Tracker

Open up a new Google Sheet. Copy and paste your roster in the first column. In each additional column, use INSERT > CHECKBOX to create a clickable checkbox. You can label the columns “Comment 1”, “Comment 2”, “Asked a question”, “Used evidence”, etc. This is a simple way to track student participation without having to shuffle papers around. This task can also be assigned to a student if you are looking for ways for students to participate when they’re on an off-day. If students have access to a view-only version, they can monitor their own progress without you having to verbally remind students to speak up.

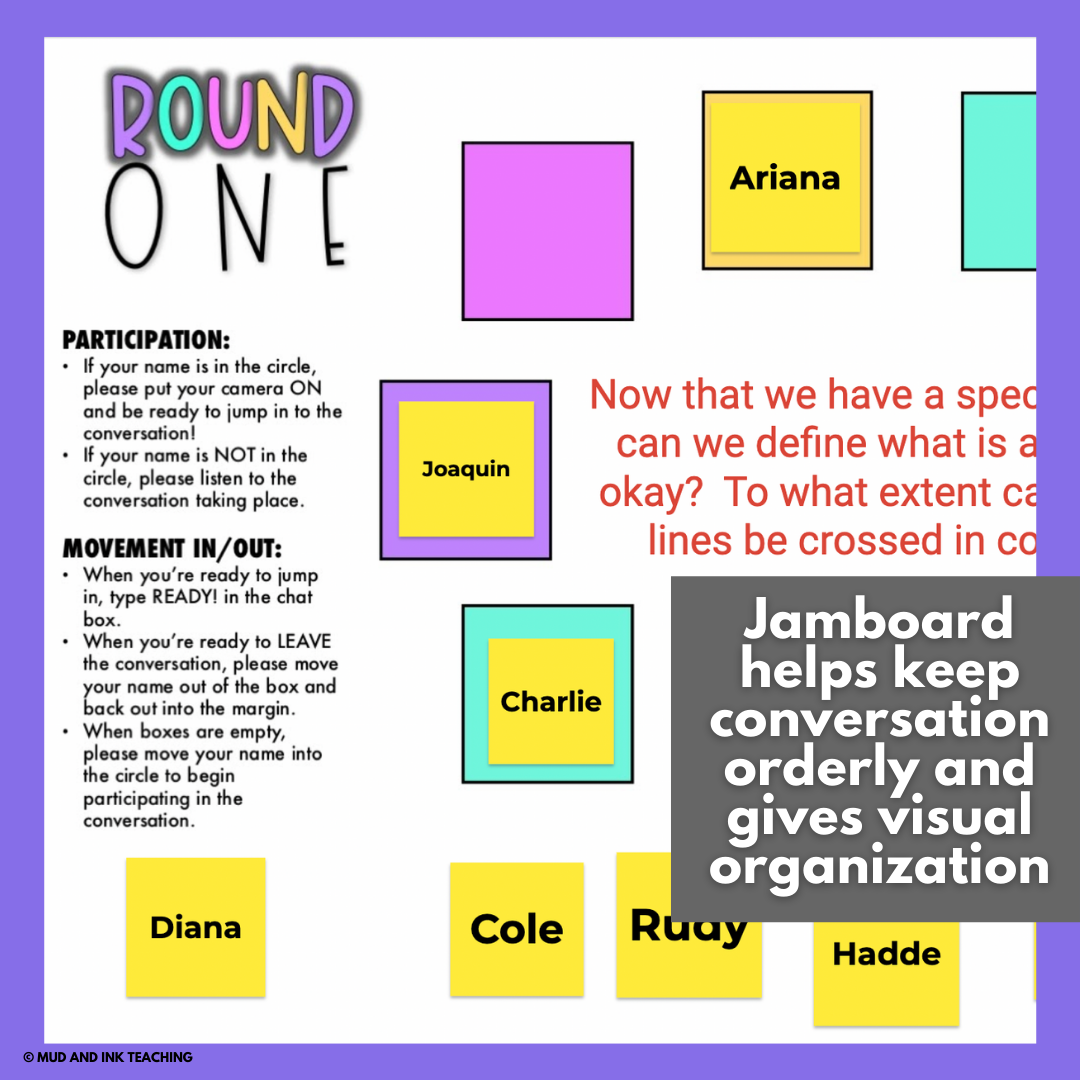

Google Jamboard

Jamboard is a unique tool that can help students keep track of who is in the circle and outside of the circle for a Fishbowl or Socratic. Using my Google Jambord templates, insert the template as the background image. Create a sticky note for each student with their first name. Give students “view only” access if you want to control the movement of students, or, leave it editable so students can move themselves inside and outside the circle. This works well for a virtual discussion or in classrooms where physically moving the desks into circles is particularly difficult.

Parlay Ideas

Parlay is an all-in-one tool that does the work of both the Google Sheets tracker and Google Jamboard. Parlay, when used for a live discussion, give students self-sufficiency and order as they navigate their difficult decisions. Whether you’re having a live discussion or a virtual one, Parlay will keep you away from logistical tasks and focused on the conversation at hand and will be delivered a data breakdown at the end of the conversation. Here are some ways I’ve used it with A Raisin in the Sun:

When to Speak Up

As much as we want our students to be engaged in a fully student-led discussion, there are times where our intercession is necessary. If we’re practicing these discussions over time, we might be intervening a bit more in the first one or two discussions, and gradually moving out as the students become more confident over time. Here are the times when we need to speak up:

If harm is done

Intentionally or not, there are times when student comments may be unnecessarily harmful or hurtful. Address these moments swiftly and clearly. Depending on the conversation at hand, you might prepare yourself for what might come up and plan ahead for how you will handle inappropriate takes on the conversation.

Time reminders

In both my seminars and my fishbowl discussions, I like to give clear indicators in time allotment. This helps students make space for others who still need to participate, be self-aware about their own contributions, and have a sense of where they stand within the class period.

A clarification/definition is needed

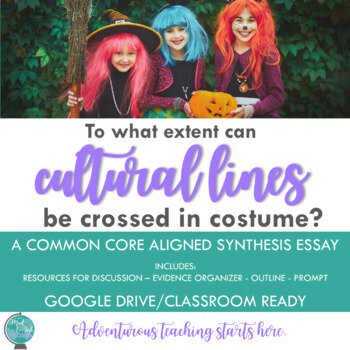

Especially when difficult topics are on the table, you might hear students skirting an argument. When my students discuss “To what extent can cultural lines be crossed in costume?” I can hear them nervously trying to not offend anyone by using generalizations. After listening for a while, I stepped in, offering a definition of “cultural appropriation” and asked them to use that definition moving forward to make delineations in their arguments. The definition helped provide clarity to the issues on the table and helped students have the language they needed to make their claims more solid.

Evidence reminders

Finally, I have found it both helpful and necessary to intervene in conversations that get too far away from the texts on the table. The generalizations mentioned above can mushroom, and sometimes I need to speak up with a quick, “Can we bring this idea back to the evidence?” or “Are there specific examples of this from something we read?” is enough to steer them back on track.

In Pursuit of Inquiry

No matter where you are in your teaching journey, know that the pursuit of inquiry and inquiry-centered instruction is the best path you can be on. Getting students to think for themselves, ask their own questions, and thoughtfully engage in important conversations is just as important as sharing great works of literature with our students.