ADVENTUROUS TEACHING STARTS HERE.

Does Taylor Swift have a place in the ELA Classroom?

And here's the thing: if your students are talking about Taylor, then so should you. This is an open door into engagement and skill building that is not to be missed. Here are three ways to pull the power of Taylor into your classroom and spike engagement among your students…

Well, let's get this out in the open: I'm NOT a Swiftie. I hope we can still be friends, but Tay Tay doesn't have a hold on me in pure Swiftie fashion. To be clear, I'm also not a hater. I'd call myself “Taylor-Neutral”.

Whether you are a die-hard fan or completely out of the scope of Swiftie life, it's impossible to ignore the continually rising wave of her cultural power. Named 2023's Person of the Year by TIME Magazine, Taylor has more than earned her spot in a national conversation – and I bet you she's part of many conversations in your classroom.

And here's the thing: if your students are talking about Taylor, then so should you. This is an open door into engagement and skill building that is not to be missed.

In some ELA teacher circles, I see a hesitation to bring the world of pop culture into our sacred space of literature and critical thinking, but here’s the thing: pop culture and trending icons of the moment are vital tools in getting our students to cross that bridge from their worlds into the deep thought and skill practice that we want so much for them. It may be Taylor today, but keep your eye on other trends that can work in a similar fashion: to create a connection and start a deeper conversation.

Here are three ways to pull the power of Taylor into your classroom and spike engagement among your students:

I already LOVED teaching my annual Person of the Year assignment, but holy smokes, this year will lead to some exciting debate. Did Beyonce get the honor a few years ago? Nope. Did Taylor? She sure did. Last year's award went to the President of Ukraine as a war raged on, and this year's award goes to Taylor…as the world continues to fall apart.

The conversations and writing possibilities around this assignment are endless, but perhaps the most interesting conversation I've ever had with students was determining the criterion for “Person of the Year”. How can a pop icon win it one year, but political leaders earn it in another? What should be considered when choosing the “Person of the Year”?

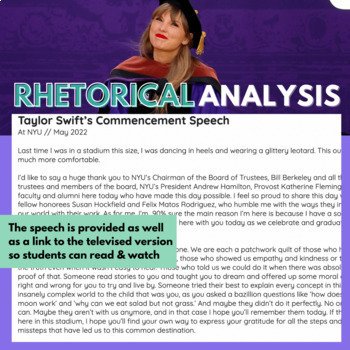

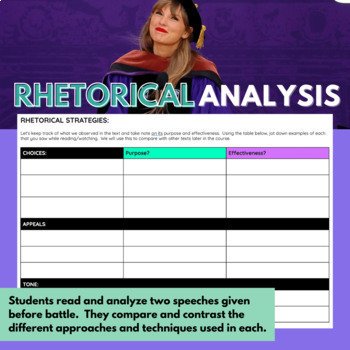

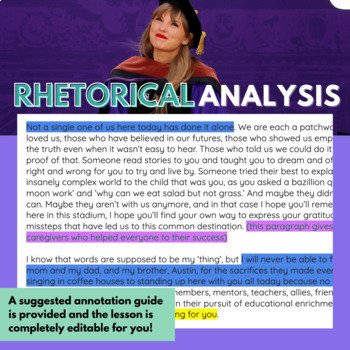

Taylor Swift's commencement address at New York University has been a favorite of teachers for a long time. This assignment is a highly engaging way to get students to practice their rhetorical analysis skills and break down Swift's approach in sending off a class of graduating students. It’s inspirational for our high school students to envision this stage of their lives - whether or not students are college-bound. The speech is about moving into adulthood and holding firm to one’s identity - a message that will resonate with all students.

This lesson is wonderful to do as an introduction to rhetorical analysis (although it is a bit longer than I’d like — I suggest cutting it a bit) or to use independently as students are reviewing what they’ve learned about SPACE CAT and rhetorical analysis.

Here's what one teacher had to say about this lesson:

“My students LOVED this activity and had some really rich, analytical discussions as a result. I did end up modifying some questions, but this resource was invaluable. The kids were super engaged because Taylor Swift is either super loved or super hated.”

— Elizabeth E

If either of those two ideas aren't what you need right now, maybe this podcast episode will give you the inspiration you're looking for. A few months ago, I had the delight of collaborating on a Taylor-Made episode of The Spark Creativity Podcast. In the episode, I share an idea for using my rhetorical triangle graphic organizer with some of her songs for a quick and engaging lesson. Many more fabulous ELA authors contributed, so make sure to give it a listen!

I hope you've got some ideas now to capitalize on the Taylor energy that seems to always be around. Have a wonderful week at school!

LET’S GO SHOPPING

Four Review Games & Activities for the AP Lang Exam

Tackle the AP Language and Composition exam with confidence using any of these four classroom-tested review strategies. This list will give you plenty of ways to prepare for the exam while having fun and working hard to get students as ready as possible for test day.

Test prep is a mixed bag of emotions for me. Teaching to any test is a quick trigger of my fury, but after time and experience with the AP Language and Composition exam, I’ve really shifted my mindset. In many ways, the entire course is test prep. The course is backwards designed: exam at the end, curriculum built from back to front to support the skills needed to perform on said exam. But what’s different about the Lang exam than any other test I’ve ever experienced in the secondary education world is that I care about these skills.

Are the timing constraints, blind prompts, and other testing factors perfect? Not by a long-shot, but time after time, I’ve seen my students flourish as writers over the course of a year as they prioritize the skills that show up on the exam.

So here’s the thing: we don’t talk much about the exam during the year. Yes, we do some timed writes, but those are for me to measure progress and less about “prepping” for the exam. But when it gets closer to exam time, we do start to talk more about the components of the exam and discuss the different ways students would benefit from reviewing the coursework and practicing the skills before test day.

These are four of my favorite review activities that I wanted to pass along. I hope you find a few gems here and can take a bit of the workload off your shoulders this May!

Choice BoardS

Not every student needs to work on the same things, and this is where a choice board comes in so incredibly handy. With a choice board, you can create categories of review study and load each category up with options that will review, give practice, or challenge students as they prepare for the exam. I design my choice boards in either Google Slides or Canva. In Slides, I build the board using VIEW —>. TEMPLATE, basically building out the “background” of the slide. Then, I add buttons on top of that background that are clickable and linked to various review materials. In Canva, I make the board, link each box, and then share a VIEW ONLY link with students. It makes no difference at all what you use — it’s all up to your comfort level. I have one made and ready to share if you want to take a peek and see if what I have will work for your students, too.

2. Mother Knows Best (Disney)

When it comes to reviewing for RA, there’s nothing more that I love than using some Disney. Disney songs (and so many other songs in musicals) are plot based, therefore, the characters that are singing often have an agenda of some sort. Take Mother Godel, for instance. After kidnapping the princess to take advantage of her magical hair, Mother Godel has a lot invested in this tower situation. It’s imperative that she keep Rapunzel in that tower locked away, so when Rapunzel starts to get a bit curious and ask questions, Mother Godel shuts down that show pretty darn fast. Using Disney songs and movies are a playful way to review RA skills, and at this time of the year should be pretty easy for students to dive into in small groups without teacher assistance. I also use these to introuce rhetoric, but a Mother Godel lesson in October is a very different from one in May. Use it how it best suits you!

3. Commencement Speeches

There are many benefits to using commencement speeches for exam review:

They fit into the end of the year feel and thematically feel like a natural fit this time of year

Commencement addresses are frequently used on FRQs if you check out past exams

There are plenty of engaging, interesting speakers to choose from all across YouTube

Depending on the speech, you might need to amend the length, but other than that, these speeches are abundant and easy to find. I like to take these speeches and break them up into pieces and make small groups experts on each piece. We then bring the pieces together for a “work as a whole” conversation and that is usually very powerful in preparation for exam day.

A few more speeches I love using:

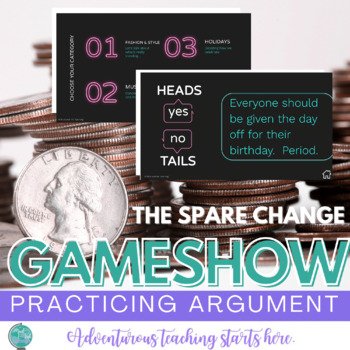

4. Spare Change Game Show

If you’re looking for a whole class, interactive, hysterical and fun way to practice argument, The Spare Change Gameshow is it. All you need is a coin to flip and a timer! Using my slide deck, students are paired up and face off arguing for and against a wide set of claims. My favorite part of this exercise is that the coin decides the students’ argumentative fate: heads must argue the affirmative, and tails must argue the negative. It makes no difference whether or not they actually agree or disagree with the claim: they must comply with their coin’s decision.

So there you have it, folks. My four favorite ways of exam prep before the AP Lang Exam. I hope one of these resonated with you and that you have a wonderful end of your school year with students. Let me know in the comments how you’re feeling this year and which of these review materials you plan on using!

LET’S GO SHOPPING

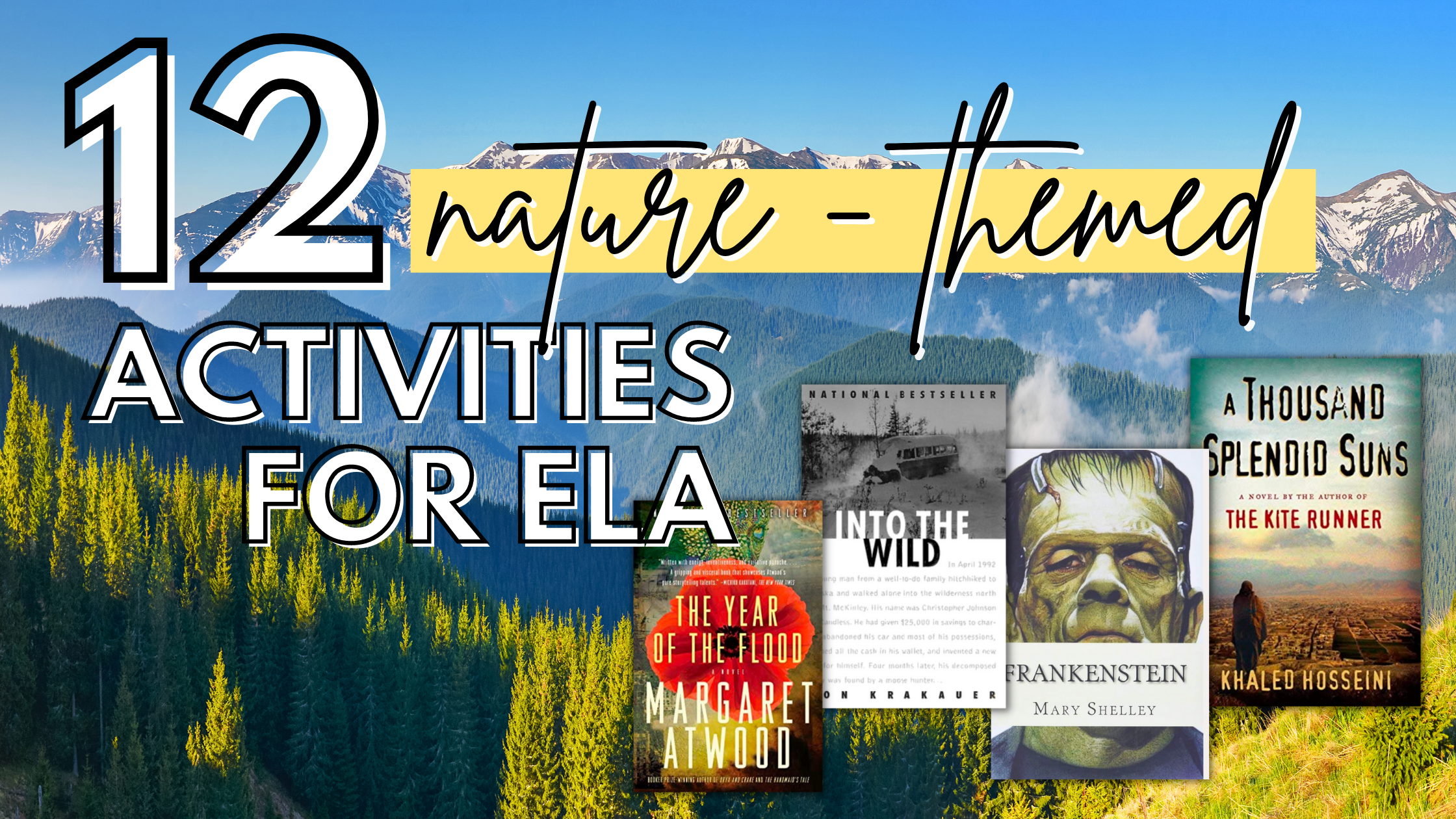

12 Nature-Themed Activities for Secondary ELA

There is a long history of connectedness between literature and nature. From the important role that setting plays in any given story to the prolific use of nature as symbolism, but I somehow always felt distant from the outdoors inside my classroom. Here are twelve lesson plan ideas to engage your students with nature.

There is a long history of connectedness between literature and nature. From the important role that setting plays in any given story to the prolific use of nature as symbolism, novels like Frankenstein, A Thousand Splendid Suns, Lord of the Flies, Into the Wild, and so many dystopian stories rely on multiple connection points with nature to fully understand the themes of the story. Even knowing this, I somehow always felt distant from the outdoors inside my classroom and found it a challenge to incorporate the natural world into my instruction as an ELA teacher.

In an effort to bring nature inside classroom walls, I grabbed eleven ELA teacher friends to give me their best ideas for connecting the beautiful outdoors with the work we’re doing in class.

1. Northern Lights Makerspace

One of my life-long fascinations has been the wonder of the Northern Lights. There’s something so magical and mysterious about the dancing lights, the way legend and folklore have been inspired by them, and one more incredible way that nature and literature have intertwined.

That’s why I had to finally create a project that did this same overlapping -- how might students in my ELA (read: not science) classroom be able to explore this phenomenon while still hitting ELA standards? And that, my friends, is how the Northern Lights Makerspace Project was born!

Here’s option #1: pair nature and poetry. Take the project in this direction, and students will learn about the Northern Lights and then transform that knowledge into a controlling extended metaphor for their lives that carries throughout their poem. Once they’ve written the poem, students then get to create their own chalk pastel drawing depicting their own vision of the Northern Lights.

And here’s option #2: look at other natural and cultural sites that are meccas for tourism. Examine the industry of tourism and special places like Machu Picchu, Easter Island, and small far-north communities that offer lookout points for the Northern Lights and ask students if tourism is more likely to have long term positive or negative impacts on the environment and community around these areas.

Let’s take a closer look here:

Creating opportunities for cross-curricular work has become a deep passion of mine over the years, and especially after the intense screen time and distance of COVID, I’m committed to finding creative, out-of-the-box ways for students to interact with their hands and with the world around them. Also — let’s acknowledge the need for students to have FUN! In Episode 129 of the Brave New Teaching Podcast, I chat about Makerspace, classroom transformations, and other fun activities that can reignite the energy in your classroom. Give it a listen below!

2. Leaf Lantern Poems

One of Simply Ana P’s favorite things about poetry is that there are SO many different types of poems. She loves introducing haikus as a short poem format, but another fun one to teach students about is the lantern poem.

A lantern is a 5-line poem, with the first line being just 1 syllable, and each sequential line increasing by 1 syllable, except the last line, which goes back to only containing 1 syllable. Below is an example:

Life

crazy

yet crucial

constant growth thrives

Live

It’s meant to represent the shape of a lantern or a bell, but it also looks great on the shape of leaves. Ana gives her student this assignment, where they create a lantern leaf poem and need to include at least 1 figurative language or poetic device (like alliteration in the example given).

It’s a short and sweet assignment, but it can last an entire class period because students take a while to decide on topics, break down syllables, and put together the art component of the project.

Students enjoy connecting with nature, and often say the hands-on piece is therapeutic.

3. MORE Creative Writing

Nature is a beautiful thing to explore with your students. Kristy from 2 Peas and a Dog believes that students need to be connected to nature in some capacity with their learning. It is probably not possible to connect every lesson to nature, but the changing of the seasons is a perfect time to get outside and explore.

Once a season, take your classes outside to collect found natural objects e.g., pinecones, leaves, branches, etc. These items will vary depending on your location.

After you return to class, have students select 1 of their found items to write a creative story about. Students can write about how it arrived at the location it was found, they could write about how it came there in the first place, or they could give the item human characteristics and write about it from that perspective.

Kristy loves giving students creative writing choices by turning season items into writing prompts. For example, she has asked students to write a love letter from a garden rake to a snow shovel explaining why they are in love with them. The responses were amazing. These types of creative writing prompts are so open ended that students really get to shine as they do not feel that there is a wrong answer.

For more creative writing information check out this blog post.

4. POETRY TO PROTECT THE PLANET

Years ago Lesa from SmithTeaches9to12 did a Buzzfeed quiz (well tons of them but this one stands out) and there was a question about whether you’d rather have a lovely picnic outside in what looked like beautiful natural surroundings or be on a blanket in a living room that was not so beautiful. Let’s just say the indoor picnic was tops! While she isn’t much for the outdoors, Lesa is a strong advocate for environmental causes and a need for change to protect our communities.

With that in mind, Lesa, in among her many poetry lessons–check them out on her blog–incorporates spoken word that is decidedly pro-environment.

Here are four options to use in your class:

You can use these performances anytime of year but if you want to tie your curriculum to specific moments then Earth Day in April is great since it also coincides with National Poetry Month.

Watch the video to do a notice and note. What do they notice about the performance? Make (jot) notes.

What are the environmental tie-ins with the piece? In what ways does it encourage the audience? Depending on time and your group of students, you can expand this reflective activity to encourage students to take action.

Get student to dive deeper into the poetic aspects - rhyme, rhythm, figurative language. Use the full text versions to help with this.

You can check out the full lesson plan with teacher answers that Lesa created for these performances.

5. PLAY WITH PERSPECTIVE

“Get your snow boots on and let’s go!” Mom would shout as the snow continued to fall from the winter sky. For Krista from @whimsyandrigor, this formed the basis of many memories growing up in the Midwest. As she and her family trudged through the snow, dragging sleds and carrying a thermos of extra hot, extra chocolate-y cocoa to Valley View Park, sometimes she would stop and notice all the boot prints in the snow.

Reflecting back, Krista realizes maybe she was also imagining what it felt like to walk in those boots. By stepping in the literal prints of another person, her vivid imagination would run wild-Were their toes as cold as hers? Were they holding someone’s hand? Would they rather be in front of the fireplace with a good book?

As a middle school English teacher today, Krista harnesses the power of playing with perspective in an activity called “Walk with Me.” This lesson focuses on helping students see new perspectives of either real people or fictional characters. It goes like this:

Students choose two characters that have different opinions or points of a view on a single topic. For example, Aven and Conner from the phenomenal middle-grade book Insignificant Events in the Life of a Cactus by Dusti Bowling or Will and Shawn from the inimitable Jason Reynolds’s Long Way Down.

Students choose a boot print handout for the first character they will write about. Help students to think analytically about the print they choose. What do the shoes say about the character?

Using the prompts on the handout (Where is this person going? What do they see? What are they remembering?, etc), students will write from that character’s point of view. (This could be in first- or third-person and could create an opportunity to demonstrate how switching perspectives impacts the reader’s experience.)

Students then choose another boot print handout and write from the other character’s point of view. Students should stay focused on the same topic or event explored in the first piece of writing. Push writers to dive deeply into what makes the characters different from one another in order to further refine their understanding.

For both perspectives, students will make inferences about each character and dive into the thoughts, feelings, worries, and hopes embodied within.

If you have time to extend the activity, students could have the two sets of prints meet and engage in a dialogue about the topic each was thinking about. If you teach how to write dialogue, this is an excellent way to have students practice those skills in a creative writing activity.

Krista loves a hallway display and these boot prints will make for a powerful visual. She suggests hanging prints in groups of two so other students and teachers can see the contrasting views side-by-side.

Getting students to metaphorically walk in the shoes of another person is a cornerstone to creating a collaborative and caring community. This classroom activity, rooted in close reading and detailed writing, encourages students to always consider other perspectives, both in literature and in life.

If you want more creative teaching ideas like this, hop onto Krista’s email list and get little surprises delivered straight to your inbox!

6. Serene Snowflake Studies

Before moving to middle school, Natayle spent several years as an early elementary teacher. One of the things she missed the most after her move was the hands-on crafts that were a staple in her earlier teaching years. While “crafts” may be a forbidden word in secondary ELA, Natayle found a way to incorporate them here and there in her lessons, particularly those related to nature.

One of the lessons that Natayle kept in her back pocket in December, January, and February (typically snow-heavy months in Colorado) was one on a commonly overlooked feature of nature: snow crystals. On one of those rare academic “flex” days (the day before a break, a half day, or following a snow day), Natayle had her students work through Snowflake Stations. They read about the original Snowflake Paparazzi, Wilson Bentley, watched a TEDed video on the science of snowflakes and got their hands busy making their very own paper snowflakes.

Her students appreciated the brief reprieve from their usual classroom routines while taking a closer look at a wintry wonder.

Learn more about Natayle’s snowflake stations here.

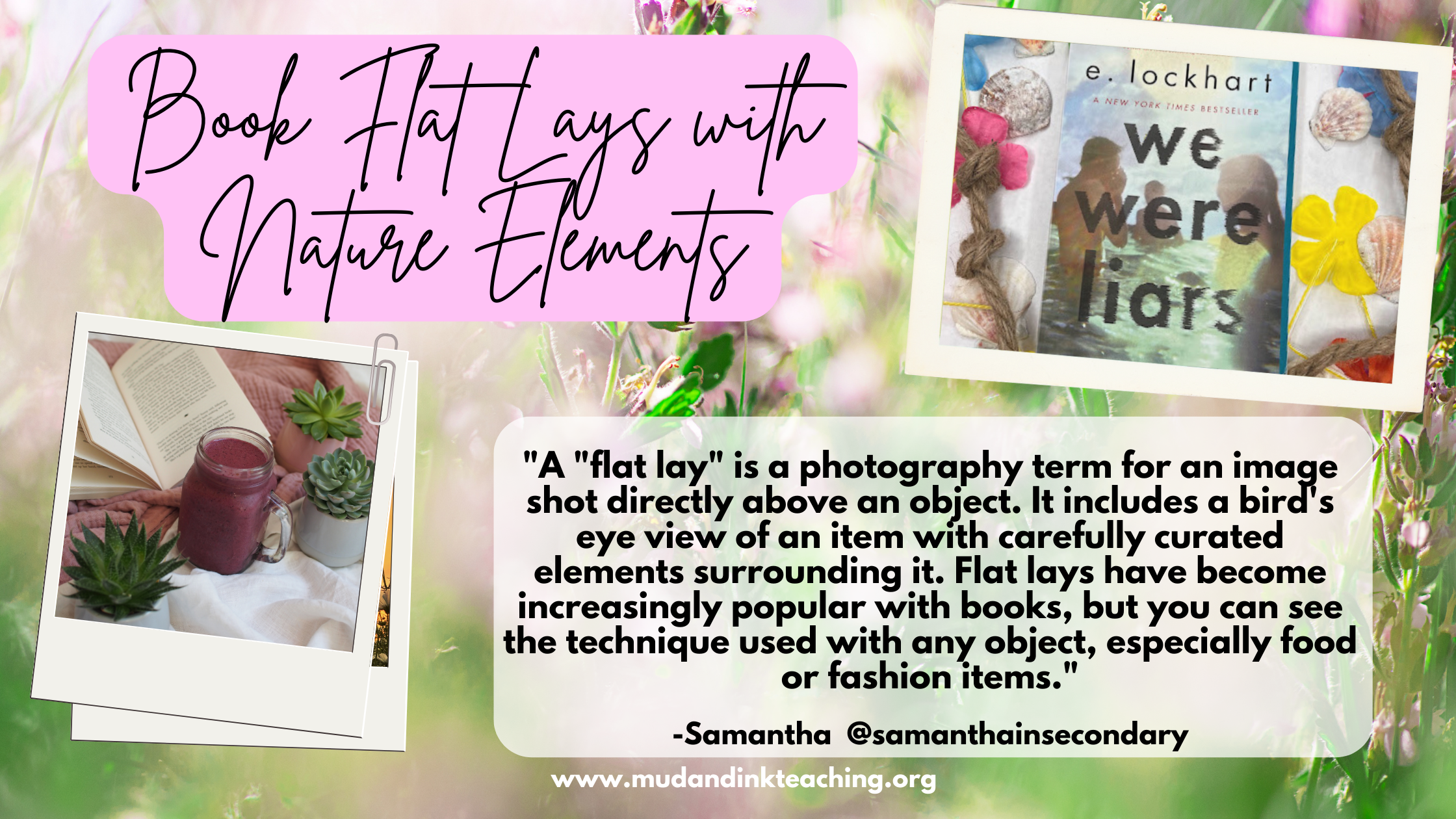

7. Book Flat lays with natural elements

Assessing a text doesn’t have to mean another essay or quiz. Samantha from Samantha in Secondary loves to shake up learning with creative assessments that work no matter what you’re reading. One of her favorite assignments is a Book Flat Lay!

SAMANTHA IN SECONDARY

“Flat lays have become increasingly popular with books, but you can see the technique used with any object, especially food or fashion items.”

A "flat lay" is a photography term for an image shot directly above an object. It includes a bird's eye view of an item with carefully curated elements surrounding it. Flat lays have become increasingly popular with books, but you can see the technique used with any object, especially food or fashion items. Samantha loves to have students curate objects based on a text and lay them out to take a photo.

Not only does this assignment lend itself to critical thinking (Which objects would be best to include and why? How do the objects directly connect to the text?), but it also provides a great opportunity to practice 21st century skills like photo editing and graphic design. Try a free platform like Canva to help your students edit their photos!

Take your students for a walk around your school’s campus to find some nature-inspired objects that could be used in their flat lays. You’ll be amazed at the creative insights they’ll gather

Looking for a done-for-you version of this activity with complete instructions, examples, and a rubric? Click here to check out Samantha’s complete resource.

8. Reading zone

After months of snow, rain, and freezing cold temps, Carolyn from Middle School Cafe looks forward to being able to spend time outside. When the temps warm up enough to spend a lazy afternoon in the park reading, Carolyn knows that spring is just around the corner!

Carolyn share's her love of reading in the park with her students by taking them outside for Reading Zone as a reward for positive behavior. Reading Zone is a magical place where students can immerse themselves in countless stories, genres, and authors. By providing opportunities for reading choice books, students will discover the true joy of reading!

Nothing motivates students more than an opportunity to go outside! By changing up the scenery and reading outside students see reading as fun and not just for academic purposes.

With choice books in hand, Carolyn leads her students to the courtyard at the back of the school. Students can decide where they want to sit - on the benches, at the tables, or even on the ground with the warm sun shining down on them. As long as they are reading, students can choose their spot.

Carolyn looks forward to many afternoons in the sun, surrounded by her students and their books! It's a perfect way to celebrate the end of winter and the beginning of a new season.

Be sure to check out this blog post for more tips and making silent reading more fun and productive.

9. literary snowman

Katie from Mochas and Markbooks works at an Indigenous high school where many of her students come from remote northern communities with strong connections to the land. Trying to find meaningful and memorable ways to connect her curriculum to the outdoors, Katie thought of the ultimate way for her students to conduct character studies in the snowy weather - literary snowmen!

If you’re lucky (or unlucky) enough to have snow on the ground, Literary Snowman Building is a cool idea to try with your students, and the best part is that your students can complete this activity at school or at home, depending on your circumstances.

The concept is simple, students build a snowman and then decorate it with items to signify a literary character.

Students can work individually or as a team and you can turn this into a fun competition by completing a gallery walk of the snowmen and asking students to vote for their favorite, or you can check out this blog post which contains a rubric you can use to assess the snowmen and determine a winner that way!

10. environmental issues bloom balls

Yaddy from Yaddy’s Room loves to use Bloom Balls as a way of getting her students involved with the environment and nature. Bloom Balls are a 3D project where students complete a task for each face of their ball based on Bloom’s Taxonomy. Yaddy’s students absolutely love putting together their Bloom Balls together and displaying them for visitors.

@YADDYSROOM

Yaddy’s students absolutely love putting together their Bloom Balls together and displaying them for visitors.

For this project, students choose one environmental issue that interests them and go deep into research, looking up facts on the environmental issue, what causes it, what effects it has, what policies have been put into practice already, who they can write to right now to tackle the issue, illustrating what the world would look like in ten years if the problem persists and so much more!

11. symbolism scavenger hunt

Olivia of Distinguished English Teacher knows symbolism is all around us, and the sooner our students realize that, the easier their academic lives will be!

One fun way to introduce symbolism is to set a timer for 5 minutes and send kids outside to find and collect natural objects like a blade of grass, a pebble, a leaf, etc.

When the kids come back in, give them five minutes to come up with a lesson they could learn from that object. Maybe the blade of grass teaches them that we should always be growing. Maybe the pebble teaches them that strength comes in all sizes. Maybe the leaf reminds them that there are seasons of life and that change can be a good thing.

As students start to see objects as more than just objects, their minds will be ready to delve into the complexity of symbolism in the literature they read.

For text-based symbolism practice, check out this fun activity!

12. “stewards of the earth” community clean-up

If you’re a nature lover, you likely have some early memories involving the great outdoors - maybe you were raised in a natural environment, or were fortunate enough to spend holidays someplace outdoors. With the growing threat of climate change, it has never been more important to help foster a love for nature with our students.

Daina from Mondays Made Easy has spent the majority of her teaching career in large cities, including Toronto and Bangkok, where the effects of pollution are quite stark. In order to instill a sense of responsibility in students, they participate in an annual “Stewards of the Earth” community clean-up. This stewardship opportunity involves time spent in nature and the shared objective of collecting trash to show appreciation for our earth.

Your community clean-up can be facilitated as a group outing, where you and your students visit a local park or green-space during classroom hours. If leaving campus isn’t in the cards for you, you can have students practice stewardship independently by picking up a piece of trash every day for a duration of time. Have students photograph each piece of trash and compile their pictures in a journal or “pollution log.” Students’ findings can be discussed in class to foster conversation about pollution in their community. Check out this free lesson on the effects of plastic waste to get the conversation started!

Whether you facilitate your clean-up as a class or independently, be sure to model safe practices to your students: ensure that they are always avoiding sharp or hazardous materials, are protecting their hands with a pair of reusable gloves, and are practicing proper hand washing after being outdoors. Speak to your science or geography departments to find out if a class set of reusable gloves can be found at your school.

4 AP Lang Skills ALL Students Should Learn

AP Language and Composition shouldn’t be the only place where students learn certain skills. In fact, these skills are so important, they should really be spiraled down into all of the grade levels leading up to Lang. Here are my top four recommendations to consider in your vertical articulation in your English Department.

I am a firm believer that any student who wants to take AP Lang and feels adequately prepared for the challenge should be allowed to take the class. That said, I spent the majority of my career in non-AP classrooms, and didn’t really know what was going on behind the AP curtain until I went to my first APSI (Advanced Placement Summer Institute). There are so many things that I’ve witnessed beginning Lang students struggle with that could easily be worked on and developed in the courses leading up to it. If you’re in a place in your career and curriculum writing journey where you’re looking to make some adjustments that help increase purposeful rigor, here are the skills to focus on.

This blog post is written in collaboration with Dr. Jenna Copper who has written her post on this same topic, but with a focus on preparing students for AP Literature. Between our two posts, you’ll have your students more than ready to embark on their AP journey in their English courses!

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS

Sometimes it can feel like there’s only time to practice analysis during summative writing assignments. If we truly want to see students grow in that area, however, we must create more opportunities within units to let students practice true analysis: discovering how the pieces of a text work together to create a whole. In AP Lang, this is done almost exclusively through nonfiction and other types of media that showcase an argument.

Rhetorical analysis is worth tackling at the younger grades, and I mean spiraling those skills beyond defining ethos, pathos, and logos. When we introduce rhetoric as a concept without the skill of analysis, there’s a lot of backtracking that needs to happen. Rhetorical analysis is not just identifying the parts (labeling ethos, pathos, logos, personification, etc.) but connecting those pieces together to figure out how they impact, shape, and build an argument.

My favorite way to introduce rhetorical analysis to students is not by showing commercials and defining the appeals. Instead, I introduce the rhetorical triangle, the argument as a whole, using a song. “Be Our Guest” from Beauty and the Beast is the perfect example of the rhetorical situation and the rhetorical triangle. Why would Lumiere use humor at this moment to convince Belle to stay? Why would he flatter her? Why would he establish his reputation as an excellent host? These “why” questions take students away from identification and toward analysis from the start. I wrote all about it and have a free sample lesson in this blog post!

I’ve even had fun (gasp!) with students practicing rhetorica in a low-stakes gameshow that I like to call: The Spare Change Gameshow. Students are faced with fun, friendly prompts and have to practice building their argument based on whichever rhetorical skill we are working on at the time. You kids will love this, and all you need is some spare change!

BUILDING / TRACKING A LINE OF REASONING

If you’re unfamiliar with the term “line of reasoning”, that’s okay. It’s a relatively new term, but it's something we’ve been teaching in writing for a long time. A line of reasoning is the thread that connects the most important structural pieces of an argument together: the thesis, the subclaims, the transitions, and all of the commentary that explains the connections that you are assembling with these pieces.

When introducing this as a concept (this is assuming students already know that there is a connection between their claims and subclaims), is through socratic seminar and fishbowl discussions. I present students with a big question and let them start tackling it. I map their conversation as they speak, tracking the beginning idea, the supporting comments, the changes in direction, the jumping off in a new direction moments, and then, I show it to them. I show them a sketch-noted, mapped conversation and discuss the line of reasoning from an initial claim to where we ended up. Discussions are messy and reading this map is often a bit confusing, but that leads us directly into a conversation about successful writing. Effective, written arguments are not the same as casual, organic conversation. Both have a line of reasoning, but the written one, the one that they are charged with completing, must have a carefully organized plan so that line of reasoning is clear, coherent, and persuasive. Our discussions eventually get somewhere deep and meaningful, but there are a lot of distractors along the way. By making this concept both an experience and something tangible they can see and hold, it helps students start to wrap their heads around this concept.

USING EVIDENCE

Teaching students to use evidence is just as important as teaching them to find evidence. Using evidence is where we find students struggling, and this directly links back to my previous two points: practice with analysis and the line of reasoning.

Accumulating some effective sentence frames is a great way to help beginning writers do this. Also, I’m here to let you know that it’s okay if the phrases used to present their arguments are less than desirable. I know that “this quote shows” is pretty annoying, but if that annoying phrase helps students get to the analysis part of that sentence, LET IT GO. Sometimes, phrases like this are just little bridges that help students get from the evidence to the commentary and analysis, and the more we harp on what phrases NOT to use, the more time and energy students spend on phrasing rather than attacking their arguments.

Coaching them with alternative options helps them get better. Instead of getting riled up, offer them frames like this:

The repetition of the word “_____” in this sentence is an indicator of the tone shifting from __________ to _________. At first the language was ________, but then the speaker starts repeating “_______” changing the energy of the conversation to ________________.

By using a (adjective) type of imagery here, the speaker reveals ___________.

Despite ______________, the speaker still argues _______________ in this line. This is important to note because _______________.

We even do this kind of practice in something I call a “paragraph chunk quiz”. On my podcast, Marie and I talk extensively about using sentence frames for formative assessment in our Masterclass: Down with the Reading Quiz.

CLOSE READING (FOR A PURPOSE)

Oftentimes, our English classes at the younger levels get bogged down with time spent clarifying plot points of the novel we’re reading in class. Monitoring students as they follow reading calendars and making sure they’re on pace is a trying task. But here’s where everything changed for me: shifting my priority to close reading.

The key to effective close reading lessons? A focused, limited purpose. When we read A Raisin in the Sun Act 1 Scene 1, we spend an entire class period close reading the Ruth and Walter scene where they fight about eggs. We watch the evolution of the eggs, the mentions of them and how they shape the tone and energy of the conversation. We walk away from that one day, that one, tiny moment of text, with a deep, layered understanding of the relationship between these two characters. Students are able to write about what the eggs symbolize and practice the skills we’ve been talking about here (analysis, using evidence) because we’ve been nose deep in the moment. You can take a look at all of my Raisin resources right over here!

By having close reading templates on hand, I can create these lessons quickly and effectively. Whether you can practice close reading with nonfiction, within novel units, with poetry, or other pieces, this is a powerful strategy to regularly use in preparing students to be stronger readers and writers as they move up in their English Language Arts journeys.

For more tips and ideas, be sure to check out Jenna Copper’s post in our collaboration between AP Language and AP Literature.

5 Common Mistakes Teachers Make When Teaching Figurative Language

Raise your hand if the first unit of your school year is a short story unit with figurative language terminology review? Yes? This is unit one in thousands of English classrooms and this makes me wonder…if they’ve done this so many times, why aren’t they experts? How is it that by unit 2, the next time we encounter an example of personification, they’ve forgotten the term altogether?

The thought process here is logical: provide terms, provide definitions, provide examples, practice, practice practice = learning has succeeded. But we see this doesn’t actually happen. So what’s not working?

I want to be very honest about this: I struggled writing the title of this article using the word “mistakes” because I don’t want teachers to feel like there’s one more thing I’m doing wrong. That’s not the heart of this at all. And let’s be perfectly clear: I’ve made ALL of these mistakes MULTIPLE times, and the reason I’m writing this now is that time, experience, training, and more experience have taught me more effective ways to do a part of our job. I wish I would have recognized these things about my attempts to teach figurative language earlier in my career. It would have prevented me from a lot of self-doubt and helped me grow my students into much more critical thinkers.

None of these “mistakes” are harmful to students. And if you’re finding these methods to be highly effective for your population, by all means, keep it up! But if you’re feeling like this is the 1,000,000,000th time you’ve tried to get kids to define “metaphor” and it’s still not sticking, stay with me.

Let’s start with our WHY

Always start here. Why do we teach the terminology, examples, functions, and use of figurative language in literature and poetry? For me, it boils down to a few important things:

These devices create an intentional effect. Analysis of the effect is important in understanding the message, the purpose, and the experience the audience is supposed to have.

These devices contribute to character development. If we value character complexity and development, being sensitive to the nuances in the details authors use to describe them requires an understanding of figurative language.

Many of these literary devices overlap with our study of rhetoric. Recognizing the tone of a particular metaphor or simile used in a speech, commercial, or other argument is important, so it’s highly valuable that this practice overlaps into two skill areas.

ONE: Rote Teaching Terminology (in isolation and otherwise)

Raise your hand if the first unit of your school year is a short story unit with figurative language terminology review? Yes? This is unit one in thousands of English classrooms and this makes me wonder…if they’ve done this so many times, why aren’t they experts? How is it that by unit 2, the next time we encounter an example of personification, they’ve forgotten the term altogether?

The thought process here is logical: provide terms, provide definitions, provide examples, practice, practice practice = learning has succeeded. But we see this doesn’t actually happen. So what’s not working?

Well, the first issue here is that language isn’t logical. And what we actually end up seeing is that the amount of time and energy we place on learning terms tells students that this is the most important part of the process. We know this is not the case (go back and look at our WHY), but in our teacher minds, we think: if they can’t identify a metaphor, how can they ANALYZE a metaphor?

I use to think this too. But then, after an Advance Placement Summer Institue, I was convinced to let go of terminology and see what happened. While close reading chapter 1 of The Great Gatsby students pointed out this line: “Two shining, arrogant eyes had established dominance over his face and

gave him the appearance of always leaning aggressively forward.” The students noted the use of the phrase “arrogant eyes” and debated how it should be identified. Was it personification? Eyes are a non-human object and certainly can’t possess the human trait of arrogance. Was it diction? Specific word choice Fitzgerald was using to create an effect?

I interjected and asked, “Tell me this: if you didn’t have to label the device Fitzgerald is using here, what would you say about this phrase anyway? Or if I told you that both labels work equally well, what do you have to say about the effect they have on characterizing Tom?”

I realized in this moment how little the term actually mattered. What mattered was that they did identify a critical description of a character. Call it diction, personification, description, connotation — that didn’t really matter in the end. But what I also realized is that students who get stuck here at this step, choosing the right term, would rarely make it to the next (and much more important) step of analyzing how this orients the reader to Tom’s character.

Releasing the pressure off of students to "correctly” identify figurative language terms might just help us move the conversation into the harder task. I give you permission to take your hands off the wheel a bit and instead of drilling them with terms, give them a word bank. Build a class website full of rich beautiful examples that you see all throughout the year. Correct students when an interpretation is completely off, but only when it has prevented them from accurate and thoughtful analysis.

NEED HELP KEEPING THE BIG PICTURE IN MIND? YOU NEED AN ESSENTIAL QUESTION AT THE HEART OF YOUR UNIT.

THE ESSENTIAL QUESTION ADVENTURE PACKS ARE HERE TO HELP.

TWO: Assessing Definitions

Let’s go back to our WHY again: if the goal of teaching figurative language is to move students toward rich analysis, then what does assessing definitions do to help us reach that goal? Let’s look at these two definitions as an example:

EXTENDED METAPHOR: a metaphor introduced and then further developed throughout all or part of a literary work, especially a poem

SYMBOLISM: the practice of representing things by symbols, or of investing things with a symbolic meaning or character.

By definition, these two devices seem to have clear differences but put into practice, students have some good questions about the blurry line between the two. In Julia Alvarez’s novel In the Time of the Butterflies, the butterfly serves as an extended metaphor (or is it a motif?) throughout the novel. Students asked me every year, “But isn’t the butterfly a symbol for the girls and the rebellion?” And year after year I carefully explained that metaphor was a better term to use because metaphor requires comparison whereas a symbol is more of a stand-in. The layers of meaning are comparative to the sisters and their experiences and metamorphosis as they grow into rebels.

The famous “Green Light” of Gatsby’s world is a symbol, though. It’s an object that pretty much means the same thing throughout the text and represents a wide variety of interpretations of ideas and emotions for Gatsby.

So here’s the mistake I realized I was making: this level of understanding how language devices function, especially in long works (as opposed to poetry), cannot be assessed by asking kids to define terms. Also, as outlined above in Mistake One, does it really matter? Does it really matter if a student discusses the butterfly as a symbol instead of a metaphor? Or the Green Light as an extended metaphor instead of a symbol? If the analysis in the sentences that come after are spot-on, insightful, accurate, and lined up with the rest of the work, I think we should let it go. I’d rather spend time here, in the text, having hard conversations, than reviewing terms or assessing students on the definitions of terms.

THREE: Teaching Too Many Terms

If you’ve ever bitten off more than you can chew, you’re in good company here. I am notorious for getting super excited about a poem or a book and trying to teach ALL THE THINGS. My excitement and enthusiasm will make the kids engaged, write?

Oof. I couldn’t be more wrong. Too many terms in the lesson or even in the unit is a recipe for disengagement and burnout. This happened to me often with close reading things like Shakespeare or even other types of poetry. Repetitiotition here! Metaphor there! Synecdoche here! Allegory everywhere! Crash and BURN.

FOUR: FORGETTABLE EXAMPLES & Lack of “Flashbulb” Moments

If you haven’t yet read Keeping the Wonder, then maybe you haven’t stumbled across the concept of a “flashbulb” moment or memory. The authors write, “When we think about the moments that stand out in our memory, it’s clear that our minds hold onto the unusual or unexpected. By tapping into students’ innate curiosity, you can design memorable, meaningful learning experiences that captivate their interest and ignite their imaginations.” (Keeping the Wonder, 2021)

This concept is vital in our instruction of particularly important literary devices. I found that when I was scraping for examples to teach definitions or make flashcards on Quizlet, the examples were often unoriginal and oversimplified. Slowly but surely, I started building up a bank of device examples that were so powerful that they were unforgettable. My favorite flashbulb literary device lesson was in teaching juxtaposition, of all things.

This was our juxtaposition flashbulb moment: the ballet scene from The Phantom of the Opera. I haven’t taught the film in a long time, but the memory of this juxtaposition lesson is still crystal clear all these years later. I even get Facebook messages from former students every now and again about this, and it cracks me up! In the scene, the Phantom is chasing the stagehand (who knows too much) back and forth across the rafters of the stage. Below them, a spring ballet, complete with sheep, goats, and baby’s breath, is underway. As the Phantom closes in on his victim (darkness, impending death), the ballet swiftly picks up pace (spring, light, and full of life). The scene ends with a shocking murder of the stagehand, giving students the perfect moment to examine WHY the juxtaposition as an artistic decision works in the scene.

Trigger warning: This scene ends with a hanging

The success of this moment, of slowing down and spending almost two class periods on one literary device (which was not the original plan, by the way!) taught me, once again, that less is more. Did I cram through a huge list of lit terms that year? No. But did my student have a life long impression, memory, and deep analysis practice with one challenging device? Yep. And we still remember it.

FIVE: Missing the Structure of Spiraling

Vertical alignment might be one of the biggest struggles for English departments across the globe. In the coaching work I’ve done with schools, I’ve found that the single-most source of frustration for teachers is that they don’t actually have a hold on what students learned before they got to them or where exactly they’re headed after their class. Teachers crave autonomy, and rightfully so, but autonomy can quickly lead to isolation and problems with skill-building.

The instruction of literary devices and figurative language analysis should ideally be spiraled across grade levels with intentionality. When grade levels select texts, standards, and essential questions are built in curriculum design, this is a layer to consider adding. Here’s an example of what that could look like and figurative language focal points that would work nicely:

FRESHMEN:

Metaphor: Long Way Down

Imagery: Children of Blood and Bone

Point of View: Frankenstein

SOPHOMORES:

Juxtaposition: The Phantom of the Opera

Extended Metaphor: In the Time of the Butterflies

Personification: Fahrenheit 451

JUNIORS:

Symbolism: The Great Gatsby

Paradox: Macbeth

Parallel Plot Structure: A Thousand Splendid Suns

SENIORS:

Allegory: The Life of Pi

Point of View: Homegoing

Flashback: The Handmaid’s Tale

Clearly, these aren’t the only things that each particular unit would cover, but having in mind the flashbulb memory opportunities that naturally exist in each text helps spiral the skills. Now, each teacher knows where each of these devices is highlighted (we’re not skipping everything else, just giving extra attention to these each year), and can align their expectations of students accordingly.

LET’S GO SHOPPING

Rhetorical Analysis: A "Hands-On" Approach

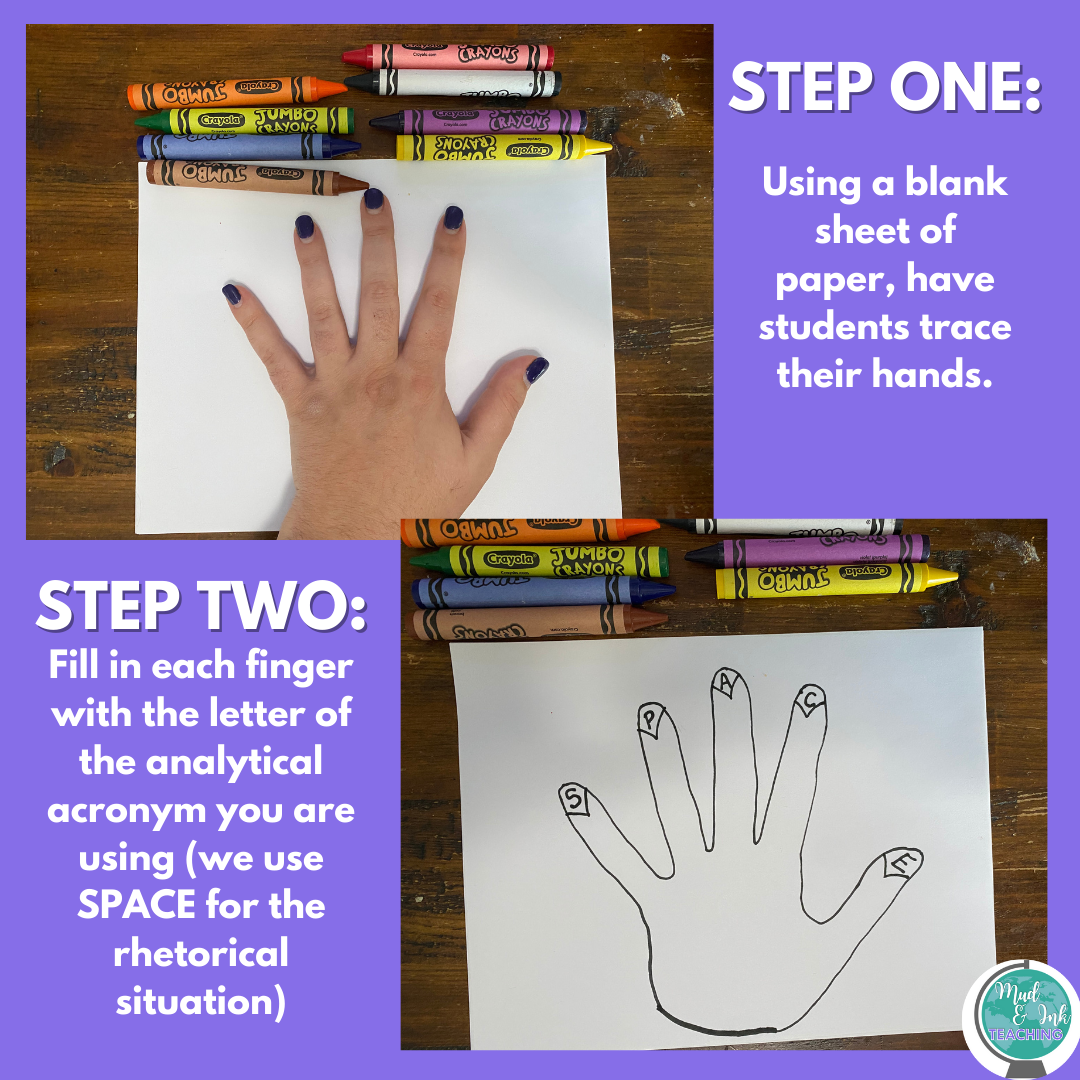

Keeping rhetorical analysis fun isn’t easy, but here’s a simple idea that requires no extra work on your end. Handprint or five-finger analysis is a memorable and creative way to analyze an argument and you can easily customize this organizer to fit any season or text you are studying.

Is it a pre-requisite that all English teachers tell bad pun jokes? I mean, I just couldn’t help myself when I was giving this article a title. Let’s get right to it.

Rhetorical analysis. Whether you’re introducing at the younger grades or a seasoned pro at AP Language and Composition, we all get to a point in the year when RA feels like a bit of a chore. There are only so many Disney lessons we can do before we need to really get down to the hard stuff, so what's a great way to shake things up without sacrificing rigor? Bust out the art supplies.

This is not the first time I’ve taken an analytical practice and attempted to make it more tactile (here’s where we made sensory bottles to imitate tone in poetry and Gatsby), and that’s because I’ve learned my lesson: IT WORKS. Moving an analytical, thinking task to a tactile experience is exactly what helps kids continue to push their skills and avoid burnout and boredom.

THE HANDPRINT ANALYSIS / FIVE FINGER ANALYSIS

Here’s what you’re going to need:

An argument to analyze

A previously taught & practiced acronym used for analysis (I like SPACE CAT)

A hand

A blank 8 1/2 X 11 sheet of paper

Coloring supplies (optional)

That’s it! I promised this would be low-maintenance.

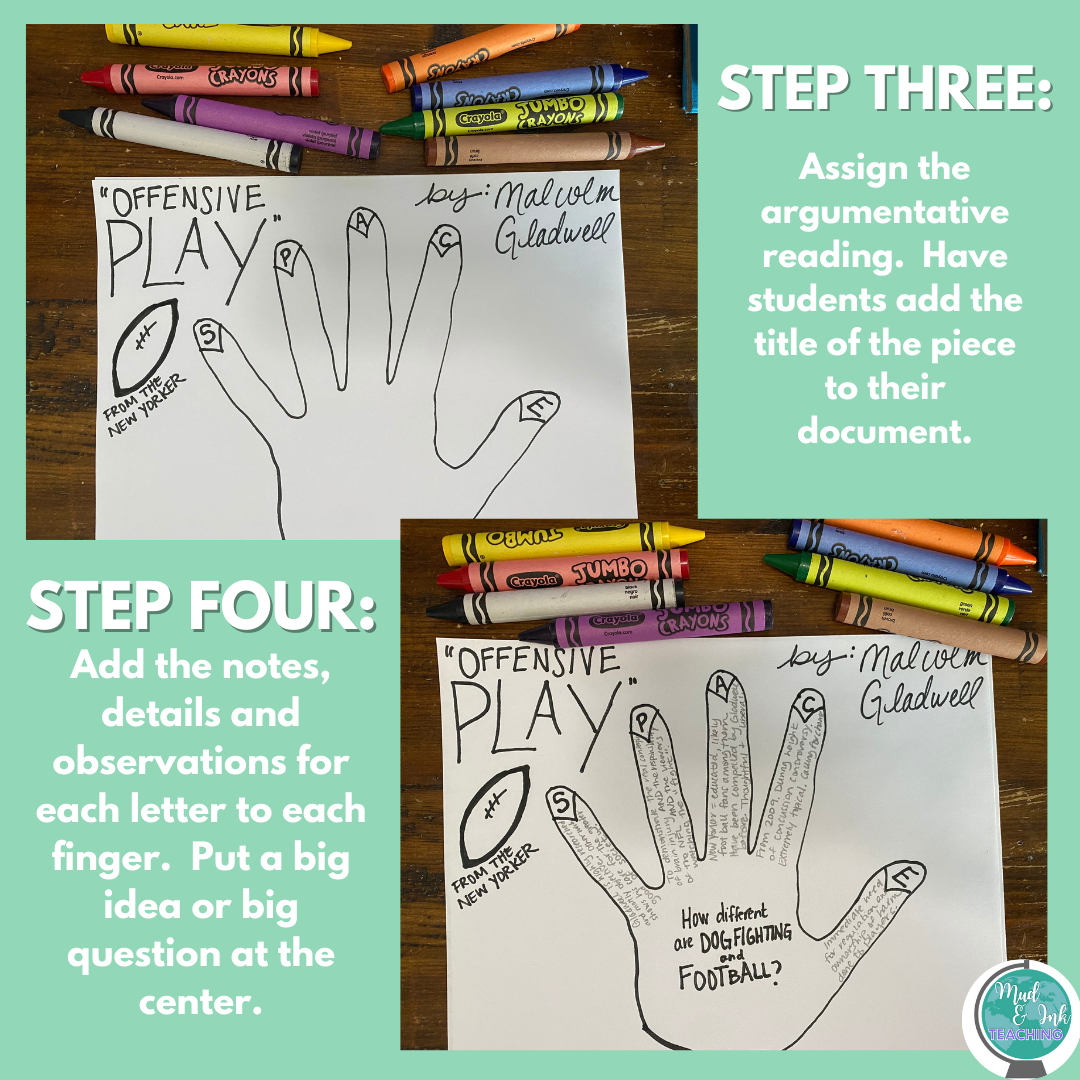

And it works pretty much how it looks:

Assign an article, speech, commercial, or other arguments

Have students trace their hand on the blank page

Assign a letter of your acronym to each finger. If you’re using SOAPSTONE, you might need to use two hands or put some of the letters on the outside of the hand. I like to use the SPACE portion of SPACE CAT to practice the rhetorical situation. If you wanted to have students continue the analysis, they could add the “CAT” portion to the inside of the hand or the margins around the hand if you’d like.

Ask students to take appropriate notes in each of the fingers.

Teach your lesson as usual with sharing, discussing, etc.

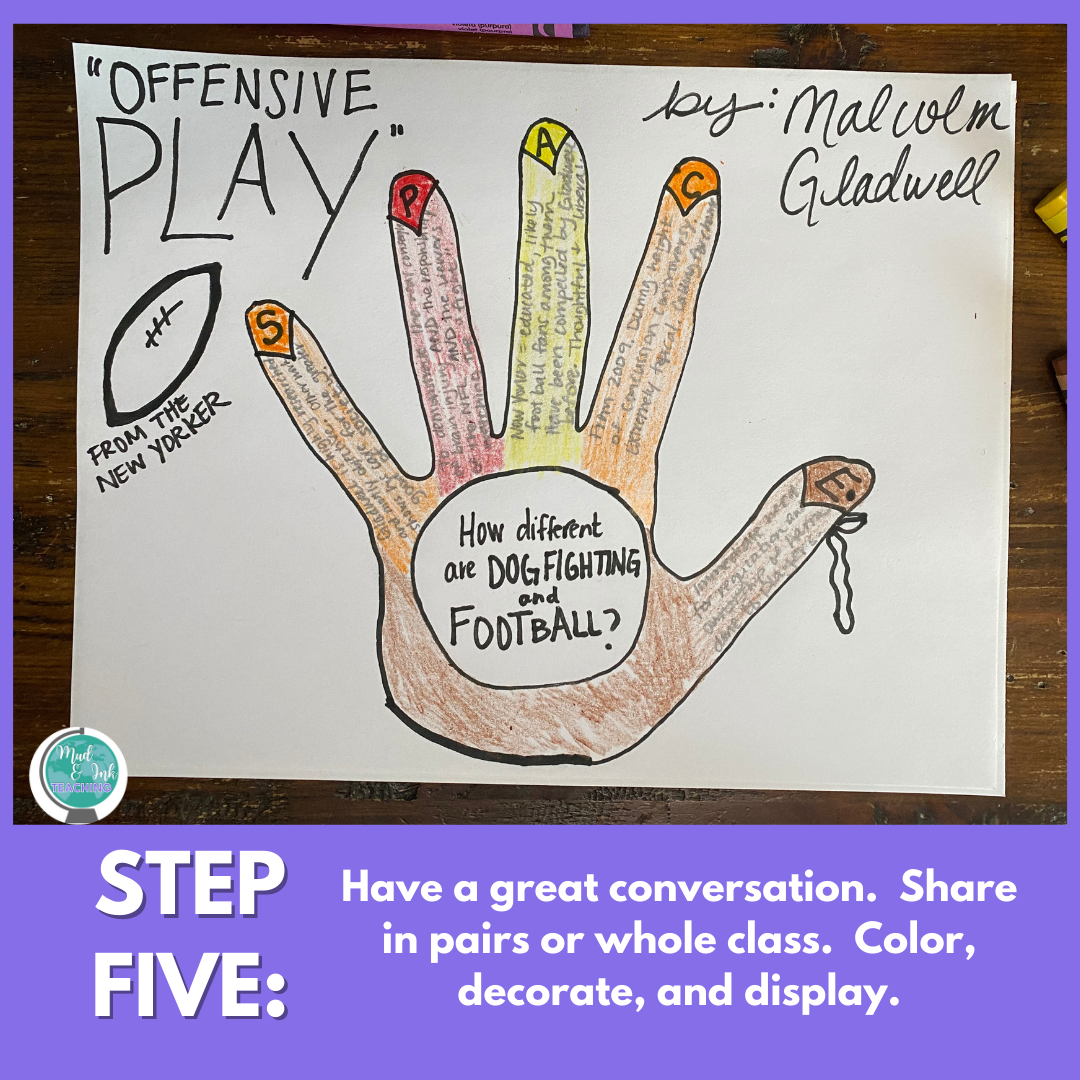

Finish off the hand-outline with a seasonal turkey (if it’s that time of year) or simply have students color the hand into some other kind of animal or object that they desire.

Display proudly.

These kinds of activities are gold for you as the teacher. You are doing and practicing NOTHING NEW, but by changing the organization and appearance of the lesson, you will breathe new energy into your week and your students will keep giving you great work.

THANKSGIVING / FALL ARTICLES & READINGS

As I’m sharing this in mid-November, I’ll share some articles and pieces that work really well at this time of year. This activity is a wonderful pre-Thanksgiving break assignment and I’ve had a lot of success with the following readings:

“Offensive Play” by Malcolm Gladwell (Thanksgiving and football are a classic combination, but after reading this article, your students will have a whole lot more to say at the dinner table about dog fighting)

The President's Thanksgiving Day Address to the Nation from Lyndon B. Johnson (1963) A Thanksgiving message delivered only days after President John F. Kennedy was killed.

Why I’m Not Celebrating Thanksgiving This Year (VOGUE) A thoughtful piece from an indigenous woman’s perspective: what are we actually thankful for?

The Dark Side of Black Friday Stuff your belly and head to Best Buy to get in line…

However you use this activity and at any time of the year, I hope this brings a little life to your classroom without a lot of planning or prep on your end. If you try this activity, please tag me on Instagram @muandinkteaching to let me see how it went for you and your students!

And if you’re new here or new to teaching rhetoric and the rhetorical situation, I’ve got you covered. I’d love to send you a full lesson plan on how I introduce rhetoric using “Be our Guest” from Beauty and the Beast! This lesson has been downloaded by over 2,000 teachers! Good luck with your teaching rhetoric journey — its a worthy endeavor and I applaud you for your efforts!

LET’S GO SHOPPING

12 Ideas for Teaching American Lit

These are 12 fresh, new ideas for shaking up your American Literature curriculum: from essential questions to literary food trucks, take these ideas to change up how you’ve done things in the past.

1. Use a Highly Engaging Essential Question

When it comes to teaching American Literature, it can feel overwhelming deciding how to set up your curriculum. Chronological? Thematic? By text? Each of these methods has their benefits and drawbacks, but by far, the most successful way that I’ve seen American Lit courses flourish is under the guidance of a highly engaging and exciting Essential Question.

In our podcast Brave New Teaching, Marie and I talk about using the question, What is America’s story? I love framing America as a story: something complicated, evolving, and crafted by the people in it. By teaching American Lit with a question rather than pre-designed topics or themes, it keeps units student-centered and focused on pursuing answers to student questions. When we look at To Kill a Mockingbird, we use the unit EQ: When injustice arises, is empathy enough? With that question, we explore everything from the skyrocketing rates of incarceration to more commonly heard narratives of injustice in America. We can look at Atticus and Bob Ewell with the same question - is empathy enough? And if not, then what is to be done? Exploring these texts, topics, and times in America’s history sparks genuine conversation among students.

2. Utilize a Literature Circle Unit

With soooo much available to cover in any American Literature class, Betsy from Spark Creativity suggests that one way to approach time periods or themes is to break them up into literature circle sets. For example, rather than have your whole class read The Great Gatsby, you might let kids choose to read The Great Gatsby, The Sun Also Rises, A Room of One’s Own, or a selection of poetry and short pieces from the Harlem Renaissance. As students work through their selection in their groups, have them share back to the class now and then, so everyone gets to learn from each other along the way. You can also bring everyone together to read complementary essays, listen to podcasts related to the era, or watch part of a documentary together.

Setting up literature circles doesn’t have to be intimidating. Start with a book tasting, and let kids find the work they’re most attracted to. Then have kids gather to break up the reading as they wish. Rather than assign the “roles” often used with younger kids, give older students creative prompts like one-pagers and character Instagram posts to guide them in responding to the literature along the way - these also make ideal visuals for helping groups share what they’re reading and learning back to the whole class.

As your students complete their works, wrap it all up with something fun like a literary food truck festival that will allow them to showcase their selection to the whole class.

3. Ask Yourself, “Who’s Missing?”

“OK-who is missing from my curriculum?” is a question that drives Krista from @whimsyandrigor as she plans for her middle school English classroom. For many teachers, this question can be uncomfortable because it forces us to answer, “Ummm, it looks like my library represents white boys and I teach zero books with a BIPOC as a central character and all of the authors I teach are white…”

Yeah...that got awkward...

Krista developed a tool, inspired by a social location wheel, that enables teachers to analyze their libraries and curriculum so they can answer “Well, my library represents all of my students because I feature books with Black, Native, queer, white, and deaf protagonists that are part of the #ownvoices movement, so, yeah, my students see themselves in our books.”

Mic. Drop.

Here’s how it works:

Download your free copy of a blank social location wheel HERE.

Gather ALL of the texts you share with students.

Dive into that massive stash of Flair pens every teacher has.

Choose a text and choose a pen.

Start filling out the wheel. It might look something like this:

After you have analyzed the first text, continue the process with the remaining books.

When you have finished, step back. What do you see? What do you NOT see? Who is there? Who is missing?

Now it is time to start researching books to fill those gaps. @buildingbooklove, @theconsciouskid, and @readingisresitance are all excellent places to begin.

If you are feeling extra empowered, take your completed social location wheel to your department chair or the administration and start having a tough discussion about who is missing.

Use #findthebookgap to connect with other educators doing the work to bring all voices into the classroom and visit Krista’s blog to get more real-life teaching ideas.

4. Engage with Social Media

Liz Taylor from Teach BeTween the Lines knew keeping kids engaged can be difficult, to say the least! That’s why she would recommend using something that they care about and know well to help guide them in their understanding of their novels and in the understanding of American Lit. Social media is the key! Having them “create an Instagram post” describing the theme/delving into the “American Dream”, or “post a tweet” from a character perspective on their American identity, can give a modern take to teaching American Literature. In her blog post, Using Social Media to Create Engaging Reading Response Activities, Liz goes in-depth with a multitude of ideas on how to make sure your lesson plans are up to date and exciting for your class! This is a fun activity for both in-person and distance learning! She even includes an idea on how to turn a protagonist’s story into a Netflix Comedy Special! These activities could work for nearly any type of novel, and the possibilities are endless!

5. Add Updated Novels Outside the Cannon

American Literature has a long history of canonical texts that are still found in many high school curricula. Samantha from Samantha in Secondary believes that one way to level up your course is to add updated novels that highlight the many complex issues in American society with a fresh lens. All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely provides a look at the nuanced issue of police brutality by viewing it through the lens of two very different main characters, Rashad and Quinn. Readers are pulled back and forth as they are shown both sides of an incident of police brutality. Far from the Tree by Robin Benway provides insight into the new American household as she explores what the term family really means. Grace, Maya, and Joaquin are biological siblings who all lead very different lives, but are brought together by a common goal. This complex, heartwarming read will truly highlight all of the intricate themes begging to be explored in an American Literature course. (You can find a longer review and teaching ideas for Far from the Tree on my blog!) Finally, Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson will give any American Literature curriculum an instant facelift. Captivating and thoroughly real, Stevenson takes readers on a journey through his years as a death row attorney in Alabama. The result is captivating. Stevenson even makes several comparisons to Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird which would make for an excellent comparative unit. I invite you to explore your own curriculum for opportunities to refresh your texts. There are so many moving, thoughtful offerings that deserve a space in your updated canon.

6. Look at America Through Motifs

Do your students have trouble crafting meaningful analysis from motifs? We often see characters in American literature chasing the American dream, uncovering their identity, feeling alienated, etc., but how does an author develop these motifs and how can we help students unfold the impact?

In her blog post, Motif Analysis: Simple Questions to Prompt Better Analysis, Kristina from Level Up ELA (@levelup_ela) shares a simple strategy which encourages students to look beyond the superficial and into the greater meanings of motifs across a text. She creates a list of 3-4 motifs in the text and assigns each student one motif to track on a graphic organizer while they read. Students document the concrete details and evaluate the context of the quotation, considering what was happening before, during, and after this quotation. Finally, she has them move into analysis. She asks them, “What does this example of the motif do? Does it reveal a theme, conflict, deeper characterization, etc.?”

By giving students the final destinations (theme, conflict, characterization), students are more likely to make more meaningful connections. Finally, Kristina groups together students who tracked the same motif at the end of the reading to share analysis and create a thesis statement and product to showcase to the rest of the class what significance the motif holds. This lends itself well to a group discussion at the end of all of the presentations exploring the common motifs of American literature and why those might exist.

7. Make Real World Connections

Often, when students hear the term “literature” they immediately think of something boring and outdated; and, as a result, they tune out. Elizabeth from Teaching Sam and Scout suggests helping students make real world connections with classic novels by pairing them with contemporary issues and current events. For example, students can debate the pros and cons of “cancel culture” (The Daily, a podcast by The New York Times, has a great two-part series on this topic that’s perfect for the classroom) while studying The Crucible, examine social media addiction and manipulation (Netflix’s documentary The Social Dilemma is a great place to start) as they read Fahrenheit 451, or discuss the 2019 college admission scandal (this investigative report from USA Today gives all the details) as it relates to the American Dream and entitlement in The Great Gatsby. By tying together “old” works and “new” issues, students are more engaged with the text, better able to see literature - yes, even fiction - as a timeless tool for social commentary, and more inclined to think critically about everything they are reading, watching, and listening to. A win all around.

8. Break Up the Serious Discussions with Humor

Much of American Literature deals with themes that are important, yet heavy. In between reading more serious works, Molly from The Littlest Teacher likes to break up the gravity with an American humor unit. Short stories are perfect for this.

Be sure to include classics such as James Thurber’s “The Night the Bed Fell” and "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” or Mark Twain’s “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” and “What Stumped the Bluejays.” Although O. Henry’s beloved “The Ransom of Red Chief” is often read in middle school, high school students would benefit from reading it again, this time with an analysis of O. Henry’s use of staple humor techniques.

For more modern American humor, check out the works of Erma Bombeck, Bailey White, Patrick F. McManus, or Dave Barry. This blog post has links to several more humorous American short stories for high schoolers that can be read online.

9. Infuse the Curriculum with Modern Texts

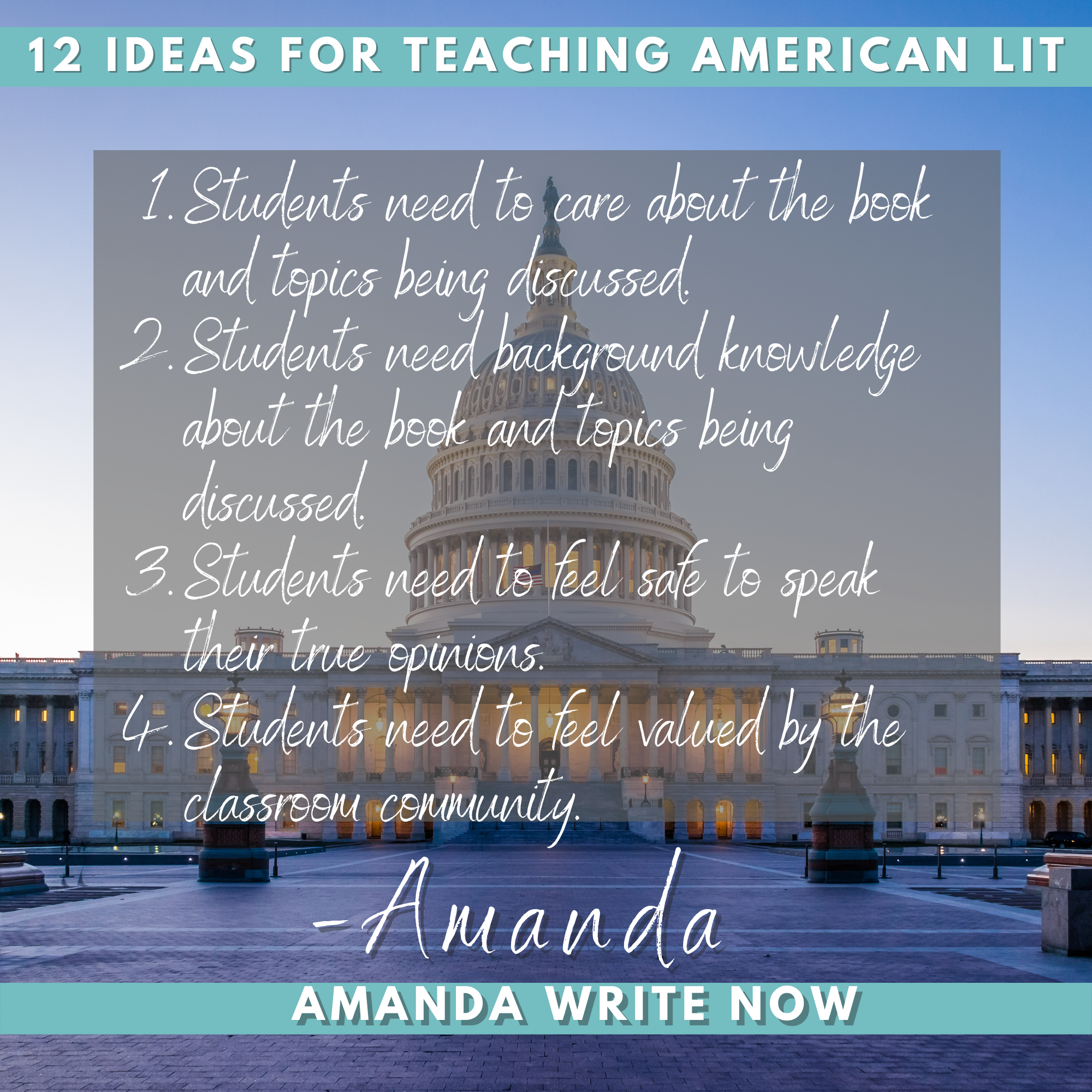

In order for students to fully comprehend American Literature and participate in meaningful discussions four things need to happen:

Students need to care about the book and topic(s) being discussed.

Students need background knowledge about the book and topic(s) being discussed.

Students need to feel safe to speak their true opinions.

Students need to feel valued by the classroom community.

Amanda from Amanda Write Now recommends reading modern American Literature and providing students with a text/media set before and during your American Literature unit in order to build background knowledge.

This text/media set can include links to articles and videos that provide students with the background they need to fully comprehend the context of the book they are reading.

For example, if you are taking a more modern approach to teaching American Literature (highly recommended if you want students to care about the book) you might choose to read All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and provide students with this text/media set.

Students also need many opportunities to write their thoughts and ideas about what they are reading before engaging in discussions. Check out this blog post that includes 15 inspiring ideas for how to help students have more meaningful discussions about literature, whether those discussions are happening online or in person.

10. Incorporate Authentic Voice

Marie from The Caffeinated Classroom LOVES using podcasts in the classroom in any way possible because they are highly engaging and novel to students. When teaching a class like American Literature, it can be easy to feel stuck relying on the textbooks or pre-written curriculum we are given, but these absolutely do not tell a full story of America.

While there is really no way to include EVERY perspective within American culture in one single course, it is possible to broaden student exposure to varied perspectives quite a bit with authentic experiences told by the people who live them.

Two of Marie’s favorite podcasts to include are Storycorps and This American Life - both tell the stories of average, everyday Americans, as well as US Presidents, and all walks in between.

When students listen to podcasts they can analyze things like the storyteller’s style and craft, as well as the overall production and experience of being a listener. After listening, having students break down an episode together and discuss their own takeaways makes for a very rich small group discussion.

If using podcasts and other nonfiction texts is something you’d like to try in your classroom, check out this blog post and video for ideas on how to work them into your curriculum and current classroom setup. ;)

11. Pull kids in with a hook

It’s all about that hook says Samantha from Secondary Urban Legends. Before starting to plan any unit, we have to think about how the topic relates to today’s learners. If they do not see the connection to their lives and what is happening around them, why would they feel motivated to read and care about themes, characters, etc. Remember, the reading makes sense in the context of the reader. The story doesn’t come alive until a reader connects with it. Pop culture is rich with sagas that you find in many American Literature texts. For example, Gatsby. New money trying to blend with old money or selling out to get ahead. What about Lord of the Flies. For sure today’s students can be hooked on the chaos vs order theme that is essential to the story and there is plenty of that to go around in 2021.

12. Be Brave & Teach Through a Social Justice Lens

I’m back here to wrap up this post with a final thought: when you teach American literature, be brave. We are teaching in a highly polarized political climate, so it feels like any social justice conversation requires us to walk on egg shells. My encouragement to you is to be brave and take on the injustices that we see in our country. I’ve had.a lot of success helping kids think about our country through metaphors. Let’s start with an athletic one: say you (student) are an athlete — an exceptional basketball player. To get to play on the college team of your dreams, however, the coaches are looking at speed, agility, ball handling, and sportsmanship. You (the student) have a few options: insist you’re already the best and have no room for growth, or, request critique from your coaches, accept their recommendations for improvement, and work on those areas of weakness. Our nation is a lot like this: we are a strong, healthy democracy founded on a vision of equality and self-governance, but we’re also a nation responsible for forcible removal of Native Americans from their own lands, a long-time supporter and proprietor of slavery, and often misguided by greed and power. We can be patriotic AND critical in the same sentence. Establishing this understanding with students helps conversations around social justice moving forward, and I hope you have the courage to have those conversations.

Thank you so much for joining us in this blog post collaboration! See you next time!

LET’S GO SHOPPING!

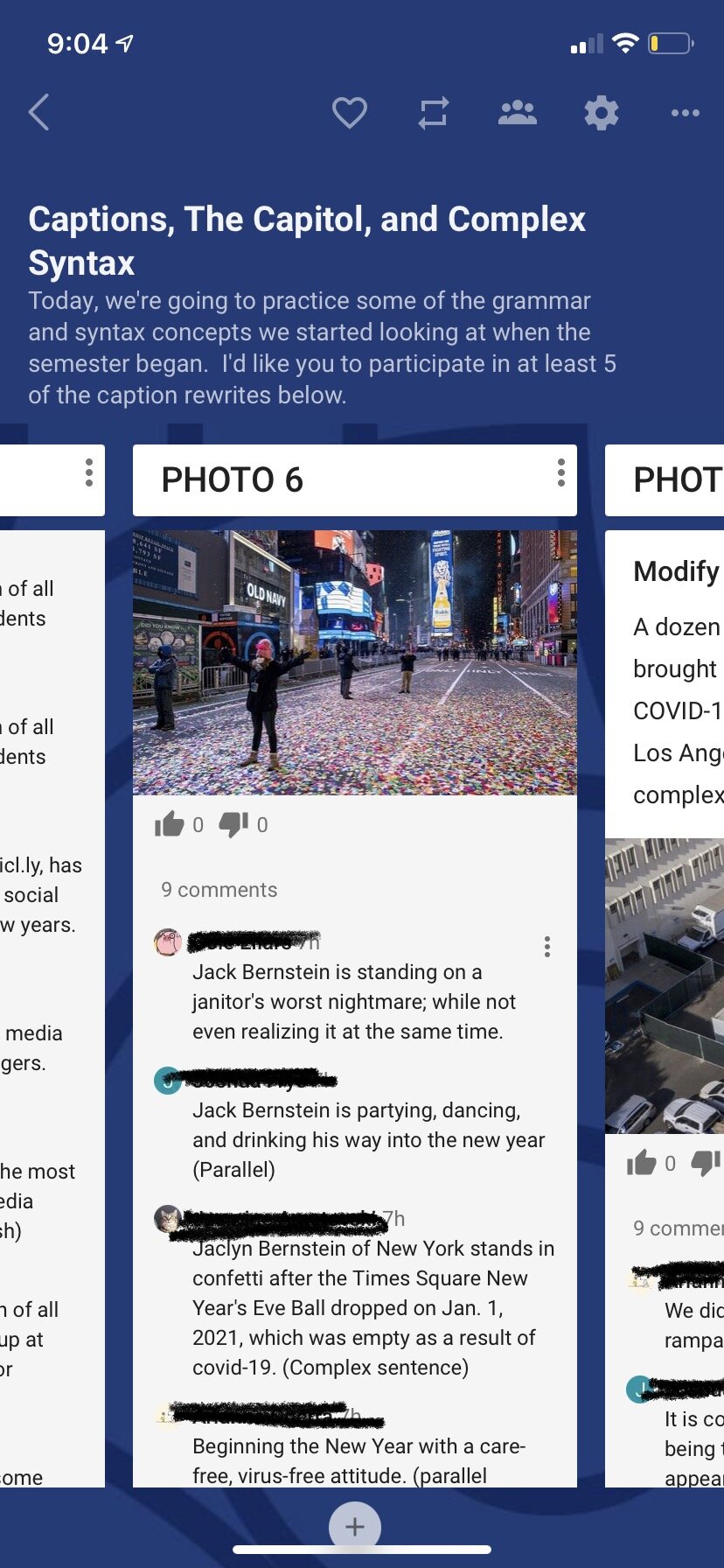

Mentor Sentences, Grammar, and Padlet: A Digital Lesson

Teaching grammar shouldn’t happen in isolation. Here is one Padlet-based lesson idea for teachers to practice grammatical concepts by writing and revising captions of various pictures.

I’m asked all the time, “How do you teach grammar?” “What workbook do you use to teach grammar?” and other variations of that question on a weekly basis. And my answer?

I DON’T.

This is not to say that I don’t teach the construction of language, the structures of punctuation, and how to proofread before submitting final work. I do all of these things. But what I haven’t done is assign a single grammar worksheet or taught any direct instruction lesson on a grammatical construct in a very, very long time.

The Grammar Teacher’s Danger Zone

There are two red flags to consider when planning for your grammar instruction: methodology and historical oppression.

First, as teachers embarking on any kind of grammar instruction, there are myriad ways to go about that instruction. Direct instruction through PowerPoint lecture, assigning work through a third party like NoRedInk, or teaching in context alongside other materials (rather than in isolation) are common considerations. Jenn Gonzalez from The Cult of Pedagogy explores research related to these options and shares clearly that grammar in isolation is not the way to go. Others here and here argue similarly. So if isolation (AKA a single Grammar Unit) is not the way to go, then let’s explore the power of teaching grammar in context.

The second danger zone that lurks in the background of the lessons we teach and the way we present grammar to students lies in the roots of oppression and colonization. In the United States, the English language was brought over from Europe and has remained the dominant language ever since. Native Americans have been long-time victims of the pressures of assimilation, especially when it comes to education. There have been mandated educational standards forcible enrollment in specially designed schools since the mid 1800s where “children were severely punished, both physically and psychologically, for using their own languages instead of English” (Klug, Cultural Survival). The message consistently sent by Standard English is that following the “proper” constructs of the language, one can be part of a more highly respected group of people. Cultural dialects and foreign languages have often been shelved at a lower place than Standard English, leaving us English teachers to sort this whole thing out as we look out at our sea of incredibly diverse voices in our classrooms. How do we teach English grammar in a way that helps students become stronger communicators and still validate the beauty and cultural importance of native languages and dialects? It’s not easy, but I can tell you right now we can stop doing two things:

circling every error we see with a red pen (or digital equivalent)

teaching full-length grammar lessons out of context

On a related note, you should hear what Vanessa has to say about teasing people about their accents:

So what DO we do?

I have a self-conscious disclaimer: this is one of my sore spots in teaching English. Grammar makes me very nervous and self-conscious, even though I mostly know what I’m doing. Honestly? I’m a terrible proof-reader. If you’ve been here on this website for any length of time, I can honestly report that I rarely do more than a quick skim to see if there are any glaring errors. If not? I publish. Readers catch mistakes all the time and I thank them, correct it, and move on.

I try to take this attitude with my students when we approach grammar instruction. Any time a grammar lesson is in play, it’s surrounded by encouragement to experiment and try. Not a single grammar lesson goes without a reminder that learning language is just another way to help my students find their voices. We learn constructs and play with them. Mostly, you’ll see grammar lessons in my classroom immediately following a major piece of writing as I teach the common errors in the context of the paper and making improvements. We also look at speaker’s and author’s syntax in writing, much like we look at diction and tone. You’ll hear me say things like: Hey! Do you see this? This is called an appositive phrase and this is where we see the speaker’s real attitude toward the subject come out! What would happen to this sentence if the appositive were taken out? That’s right! This would have been a pretty neutral sentence if it wasn’t for that side-comment appositive phrase. Let’s try manipulating that ourselves…

What does this look like with technology?

One lesson that I shared on social media recently is a caption writing activity that uses Padlet. Padlet’s software is free for three uses, and then moves to a paid tier. This activity is great because you can complete the activity, keep it live for a while, and then delete it — freeing you up to use Padlet again for another lesson.

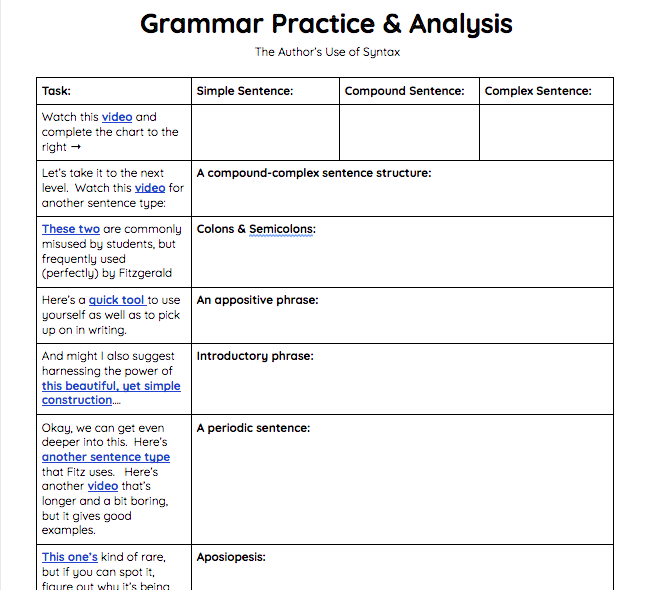

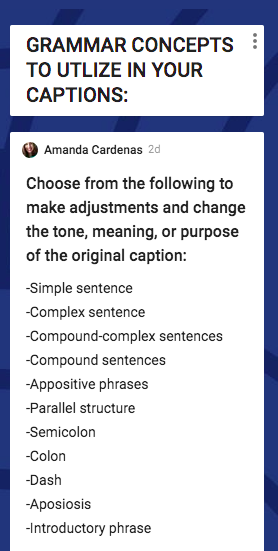

STEP ONE: CHOOSE AND TEACH THE GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

To do this, I built my students a YouTube playlist and sent them out to watch, take notes, and collect examples of 10 different grammatical concepts with varying levels of difficulty. About half of them were probably familiar to students from previous years of their education (this is a lesson I did with 11th grade) and the other half were probably new or generally unknown to them. My handout looks like this:

STEP TWO: PRACTICE AND PLAY

Once my students had a working knowledge of these concepts, we started looking at examples from literature and from of the major works we study for rhetorical analysis. We discussed Fitzgerald’s use of aposiopesis when he ends The Great Gatsby with the lines:

“Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther.… And then one fine morning—

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

We also looked at Elie Wiesel’s simple, yet powerful use of a semicolon at this point in his speech “The Perils of Indifference”:

“We are on the threshold of a new century, a new millennium. What will the legacy of this vanishing century be? How will it be remembered in the new millennium? Surely it will be judged, and judged severely, in both moral and metaphysical terms… So much violence; so much indifference.”

These discussions served two major teaching points for me: one, they put grammar into context, which as we know from the above research is imperative, and two, this is how I help students learn what analysis looks like. We can identify aposiopesis and a semicolon with relative ease, but the discussion about how and why are they effective given the context is where I want my students to be in their writing.

Now, it’s time to play. Enter: PADLET.

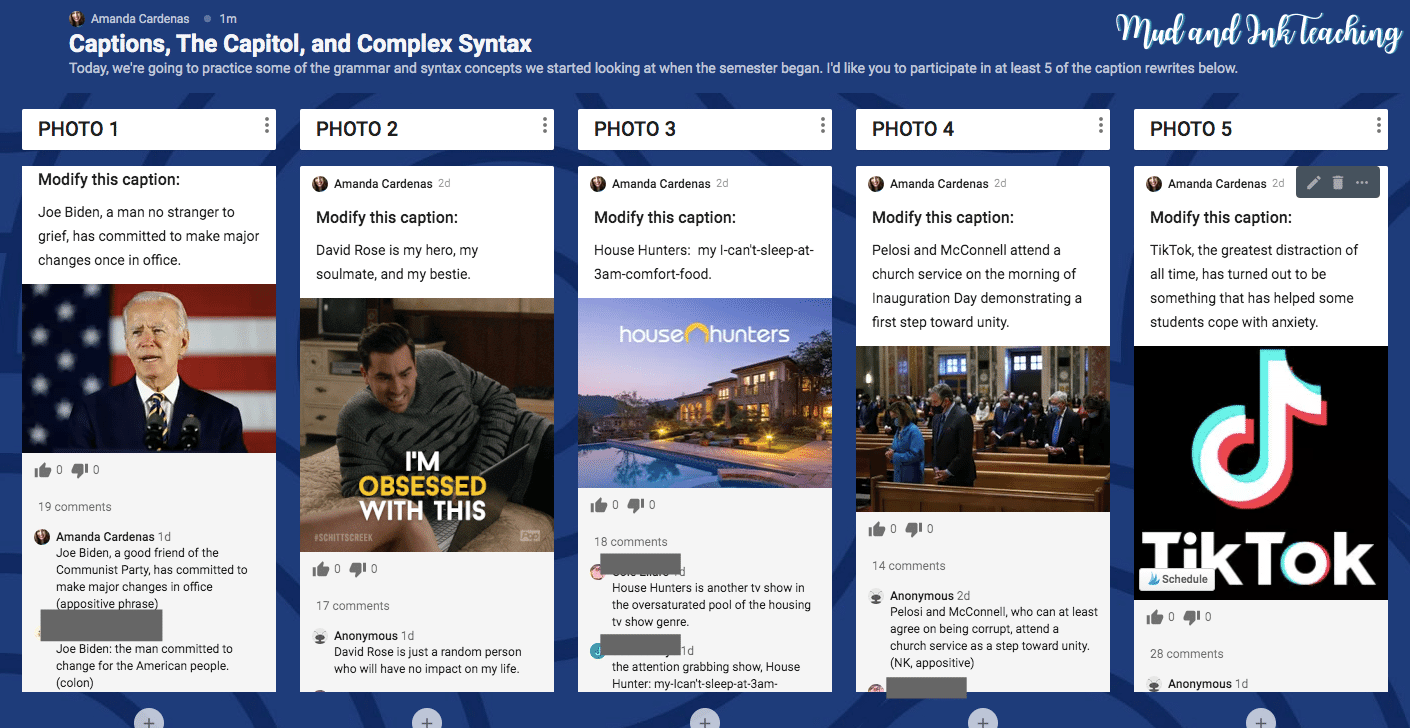

The idea behind this Padlet lesson is for students to manipulate language to create a noticeable change in meaning, tone, or purpose to a given sentence. Here’s how I set up the Padlet:

Head over to Padlet and login with your credentials. Click Make New Padlet.

Choose the SHELF option to set up the lesson the same way that I did. This option is what I use for any gallery walk type of lesson.

On Shelf 1, provide your instructions and any other notes for students to reference as they work.

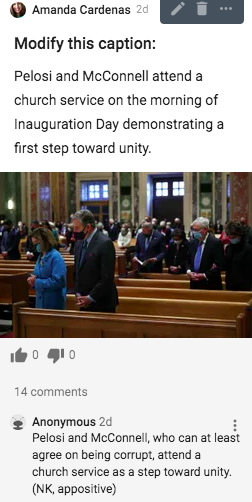

On the remaining shelves, provide an image and a neutral-ish caption. For this particular sample, you’ll see a variety of images that are connected to what our class discussions have been about recently. The variety is key: choice in this lesson is critical so that students can find a comfort zone where they can experiment without feeling overly restricted.

Ask students to login to Padlet. This makes it easier to see who comments as it will automatically display their names.

Students now can see all of the images and captions and choose five (that’s what I asked for!) of them to modify using a grammar construct that we practiced earlier in the week.

That’s the gist! Afterwards, I had students read through the Padlet and upvote their favorite sentences, they pulled examples from the Padlet to analyze in small group breakout rooms, and, ultimately, complete a self-evaluation on their growth and progress in their ability to identify and analyze these concepts.