ADVENTUROUS TEACHING STARTS HERE.

Does Taylor Swift have a place in the ELA Classroom?

And here's the thing: if your students are talking about Taylor, then so should you. This is an open door into engagement and skill building that is not to be missed. Here are three ways to pull the power of Taylor into your classroom and spike engagement among your students…

Well, let's get this out in the open: I'm NOT a Swiftie. I hope we can still be friends, but Tay Tay doesn't have a hold on me in pure Swiftie fashion. To be clear, I'm also not a hater. I'd call myself “Taylor-Neutral”.

Whether you are a die-hard fan or completely out of the scope of Swiftie life, it's impossible to ignore the continually rising wave of her cultural power. Named 2023's Person of the Year by TIME Magazine, Taylor has more than earned her spot in a national conversation – and I bet you she's part of many conversations in your classroom.

And here's the thing: if your students are talking about Taylor, then so should you. This is an open door into engagement and skill building that is not to be missed.

In some ELA teacher circles, I see a hesitation to bring the world of pop culture into our sacred space of literature and critical thinking, but here’s the thing: pop culture and trending icons of the moment are vital tools in getting our students to cross that bridge from their worlds into the deep thought and skill practice that we want so much for them. It may be Taylor today, but keep your eye on other trends that can work in a similar fashion: to create a connection and start a deeper conversation.

Here are three ways to pull the power of Taylor into your classroom and spike engagement among your students:

I already LOVED teaching my annual Person of the Year assignment, but holy smokes, this year will lead to some exciting debate. Did Beyonce get the honor a few years ago? Nope. Did Taylor? She sure did. Last year's award went to the President of Ukraine as a war raged on, and this year's award goes to Taylor…as the world continues to fall apart.

The conversations and writing possibilities around this assignment are endless, but perhaps the most interesting conversation I've ever had with students was determining the criterion for “Person of the Year”. How can a pop icon win it one year, but political leaders earn it in another? What should be considered when choosing the “Person of the Year”?

Taylor Swift's commencement address at New York University has been a favorite of teachers for a long time. This assignment is a highly engaging way to get students to practice their rhetorical analysis skills and break down Swift's approach in sending off a class of graduating students. It’s inspirational for our high school students to envision this stage of their lives - whether or not students are college-bound. The speech is about moving into adulthood and holding firm to one’s identity - a message that will resonate with all students.

This lesson is wonderful to do as an introduction to rhetorical analysis (although it is a bit longer than I’d like — I suggest cutting it a bit) or to use independently as students are reviewing what they’ve learned about SPACE CAT and rhetorical analysis.

Here's what one teacher had to say about this lesson:

“My students LOVED this activity and had some really rich, analytical discussions as a result. I did end up modifying some questions, but this resource was invaluable. The kids were super engaged because Taylor Swift is either super loved or super hated.”

— Elizabeth E

If either of those two ideas aren't what you need right now, maybe this podcast episode will give you the inspiration you're looking for. A few months ago, I had the delight of collaborating on a Taylor-Made episode of The Spark Creativity Podcast. In the episode, I share an idea for using my rhetorical triangle graphic organizer with some of her songs for a quick and engaging lesson. Many more fabulous ELA authors contributed, so make sure to give it a listen!

I hope you've got some ideas now to capitalize on the Taylor energy that seems to always be around. Have a wonderful week at school!

LET’S GO SHOPPING

20 Speeches and Text for Introducing SPACE CAT and Rhetorical Analysis

During the introductory phases of teaching rhetorical analysis, you need to start off with texts that are approachable and teachable. This helps to build student confidence as the texts get harder and harder each year. Here are 20 places where you can start that journey confidently!

When it comes to introducing rhetorical analysis for the first time, choosing texts can feel like an intimidating task. But before you get bogged down with which text to pick, let’s talk through a few initial steps to help ensure your success.

TIP #1: Begin with a Framework

When I first was told to “teach rhetoric”, I had virtually no training or support. I resorted to what I knew from my undergrad: an overview powerpoint about ethos, pathos, and logos. This is exactly the path that I would actively AVOID if at all possible (I’ve written about that more here), and instead begin by introducing students to the framework that you’ll use in order to do the work of analysis. For me, I’ve found SPACE CAT to be my favorite ( BTW, I also do this with poetry using The Big 6).

TIP #2: SKIP ETHOS, PATHOS, LOGOS IN YOUR INTRO

Okay — hear me out. I’m not saying don’t teach ethos, pathos, or logos. I’m saying don’t use that as an INTRODUCTION to rhetoric.

Here’s why:

Whatever the first thing is that students learn is going to be the thing that they think is the most important. And to be perfectly honest — the appeals alone are NOT the most important part of rhetorical analysis.

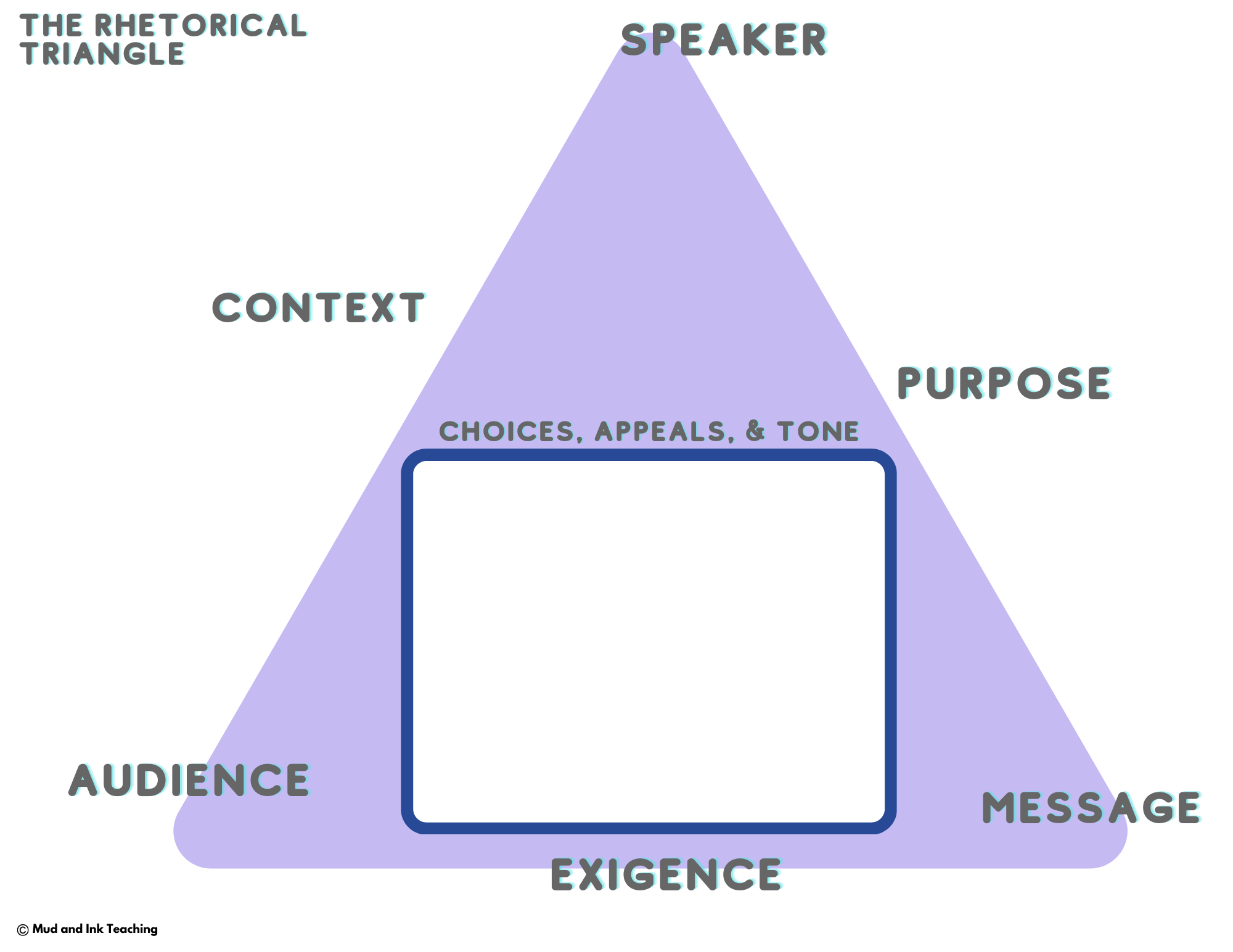

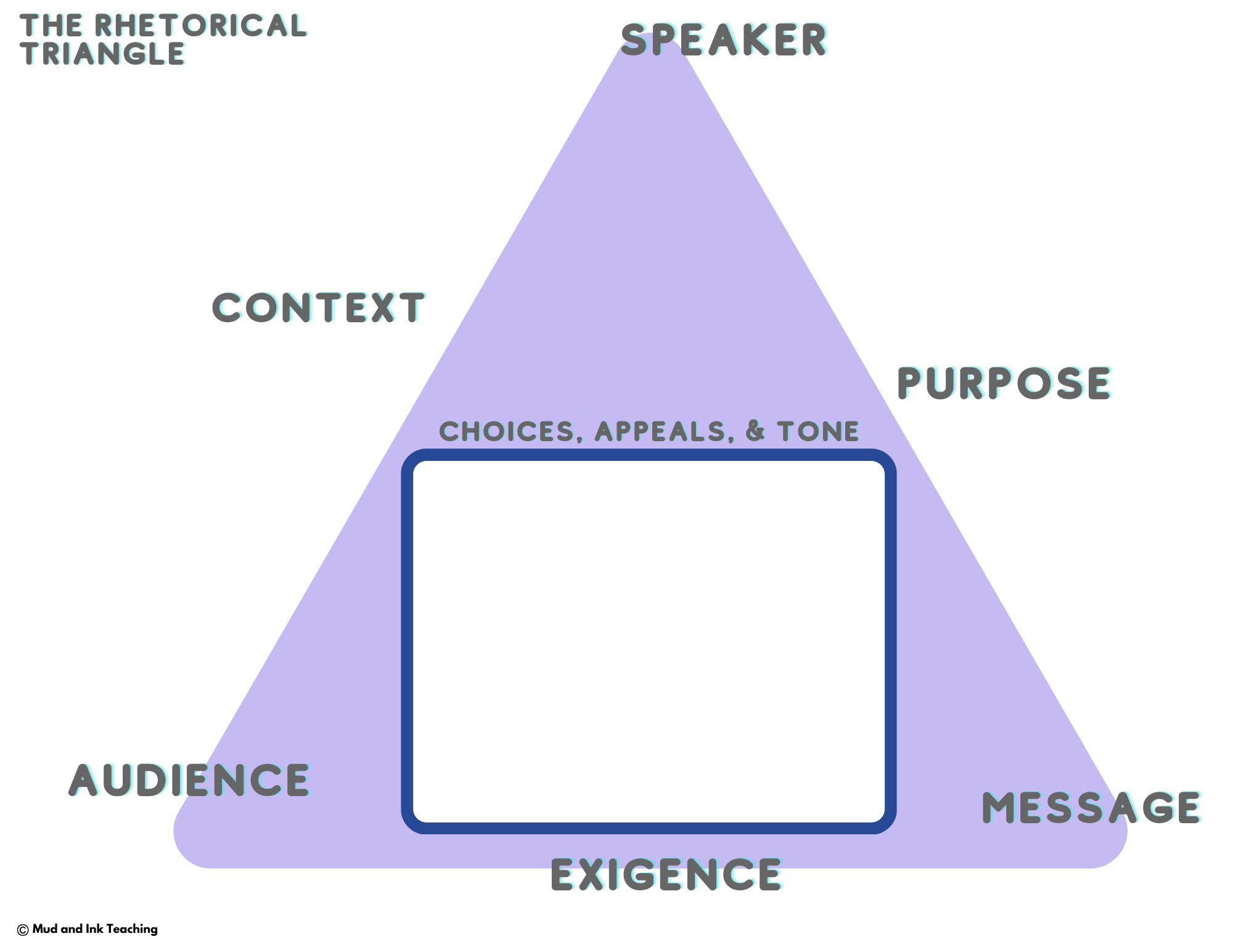

So what to do instead? Introduce the RHETORICAL TRIANGLE.

The Rhetorical Triangle sets students up to see the ways in which an argument moves from one person to another. It centers students on their role as analysts and the need to be inside of the argument - not outside attacking it with a highlighter.

For two more in-depth discussions and lesson examples on the rhetorical triangle, start here:

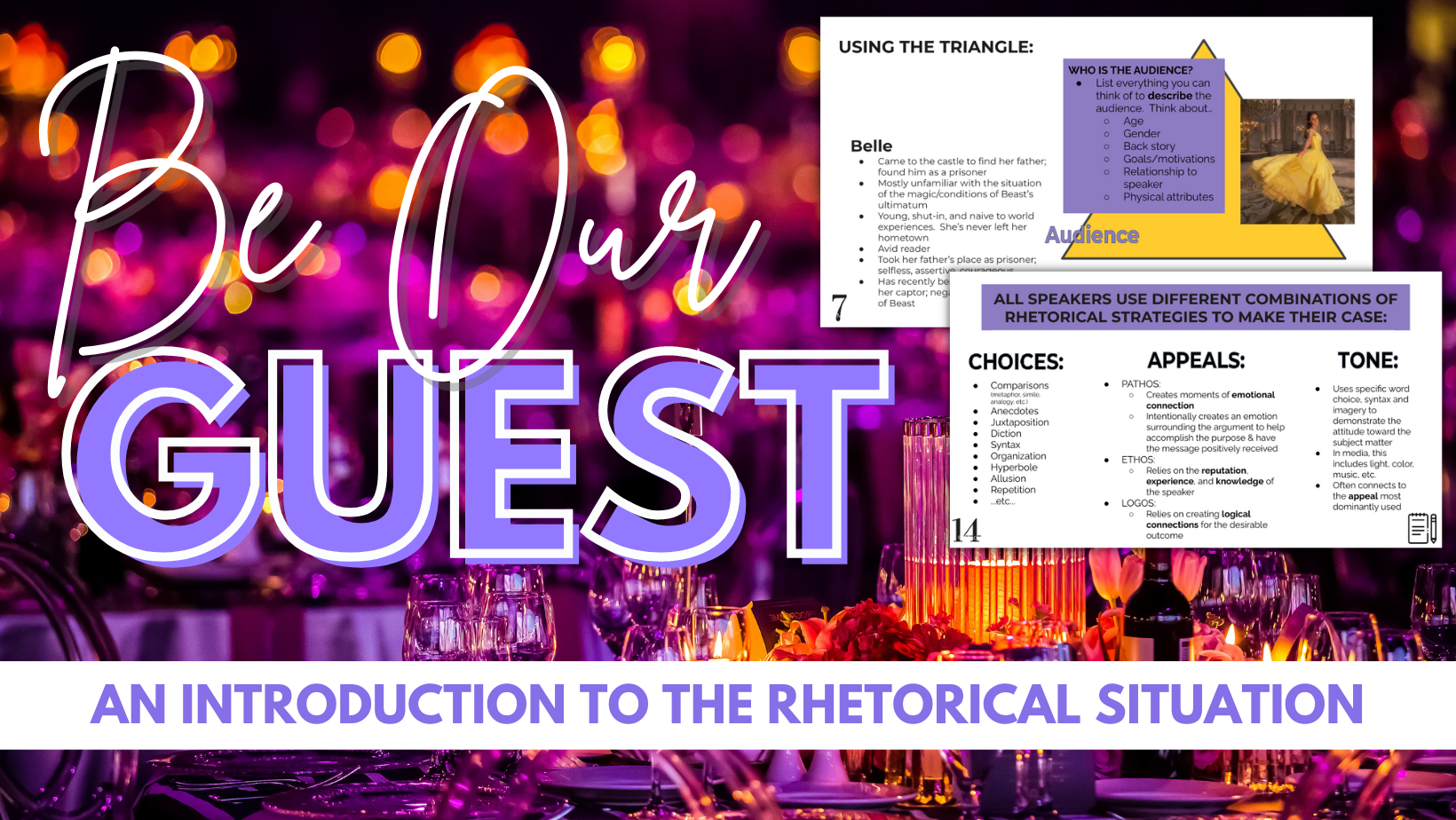

“Be Our Guest” from Disney’s Beauty and the Beast

“Mother Knows Best” from Disney’s Tangled

TIP #3: TEACH ON REPEAT

If you’ve not started “template teaching” let me encourage you to make this the day that you start. As you browse through the list below, try to think of these texts as opportunities to teach and reteach the same skills over and over — not a daunting list of individual lesson plans.

Begin by introducing the rhetorical triangle and situation using either of the two lessons listed above. During those lessons, introduce students to the rhetorical triangle graphic organizer template and help them become well acquainted. This graphic organizer will be the TEMPLATE to print and repeat for every lesson hereafter.

Once students are ready to move to more challenging texts, start movin’. What’s the lesson? It’s all baked in to your graphic organizer template. Using just that one handout, students can do a huge variety of tasks all with varying levels of challenge and independence. Here are a few ideas:

In small groups, bullet point details about the speaker. SHUFFLE GROUPS, and in the new group, bullet point details about the audience, SHUFFLE GROUPS, and in the new group bullet point details about the context. Repeat as needed for each element of SPACE.

Read/watch the text together. Complete S - P - A together and assign C - E to work on in pairs

Put students in small groups. Designate areas/tables around your room as S, P, A, C, and E. Have students move through each station with their group and their handout to analyze the text.

Have students choose any text from a provided list and complete the graphic organizer independently for homework / individual work

This template allows you to flex the details of your lesson without having to prep brand new handouts for every single new text!

THE LIST YOU’VE BEEN WAITING FOR: THE BEST TEXTS FOR INTRODUCING SPACE CAT

This list comes both from personal experience and teacher recommendations. If you have experience or more ideas, please feel free to add them to the comments at the end of this post!

“The Other Side” from The Greatest Showman

Battle speeches from Queen Magra and Baba Voss from the Apple TV Series See

“Be Prepared” from Disney’s The Lion King

“I’ll Make a Man Out of You” from Disney’s Mulan

“Under the Sea” from Disney’s The Little Mermaid

“How to Mark a Book” by Mortimer Adler

“Farewell to Baseball” Lou Gherig

Challenger Speech from Ronald Reagan (and grab my close reading template for this speech here)

9/11 Address from George W. Bush

“Offensive Play” by Malcolm Gladwell

Back to School Commercials

What would you add to this list? I’d love to hear it in the comments below!

Happy teaching!

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS RESOURCES

11 Best Movie Scenes to Introduce Rhetorical Analysis

Rhetorical analysis is a skill that needs practice and reinforcement all year long. Using various moments from movies and film offer a great chance to examine both the rhetorical situation and the arguments themselves. Check out these eleven movie suggestions to teach rhetorical analysis including various Disney movies, The Notebook, and We Are Marshall.

Teaching students to write rhetorical analysis is probably one of the hardest things I had to learn as a teacher. And if you’re a teacher of rhetoric, you know exactly what I mean. If you need a deeper, more philosophical step by step guide, I have a blog post for that, but if you’re feeling good but in dire need of ideas for lessons, that’s what I’ve got for you right here.

One thing I’ve found over my years of experience in teaching rhetoric is how incredibly helpful it is to have a fictional scenario to use to teach argument. When the rhetorical situation is rich, it makes connecting the dots easier for students and also keeps them from feeling compelled to highlight and annotate a bunch of devices without understanding why.

To lend a helping hand, I’ve compiled a list of great moments from film that present opportunities to teach both the rhetorical situation as well as the arguments themselves. If you don’t already have a template to use for teaching rhetorical analysis, I’ve got you covered!

#1: “Be Our Guest” from Beauty and the Beast

This is my favorite one to use when introducing the rhetorical situation. I have a ready-to-go lesson right here if you need it!

#2: “Mother Knows Best” from Tangled

Mother Godel has a mission: keep Rapunzel locked away. But when she starts to get curious about leaving her tower, this song puts Rapunzel back in her place.

#3: “The Other Side” from The Greatest Showman

PT Barnum needs a cash infusion to make his circus dreams come true and there’s only one person that can help him. Watch this argument weave through an incredible song and grab a pre-made lesson plan here if you are in a pinch!

#4: “Going to Battle” from the Apple TV series See

The war is imminent. The odds are against them in every way. Here are two going to battle speeches that will get your students ready to go! If you need it, I’ve also got this one written for you — check it out below!

#5: We Are Marshall

There are many athletic pump up speeches out there, but this one takes place at the grave site of players that have come before them. Buckle up for this classic from Matthew McConaughey.

#6: Titanic - Don’t Jump

Jack catches Rose at her lowest point and has to convince her to rethink her situation. Use this with caution, however, because the suicidal premise may not be suitable for your group.

#7: The Notebook: Allie & Noah’s Fight

He’s already lost her once, and this time, he’s fighting to keep her around. There’s some fun language in this one, but other than that, it’s short, sweet, and memorable.

#8: Toy Story 3: Woody’s Speech

I’m going to need you to try really hard and keep it together for this final speech to Andy’s toys. In his speech, Woody tries to encourage the crew to keep an optimistic outlook on their future despite the doubters in the room.

#9: Frozen “Do You Want to Build a Snowman?”

Elsa? Wanna come and play? Sadly, she doesn’t, but that doesn’t stop Ana from trying.

#10: Grey’s Anatomy: Pick Me, Choose Me

This is DEFINITLEY the corniest (and probably the weakest) argument on the list, but that just makes it even better to pull apart. Did Dr. Grey’s speech do enough to win over Mc. Dreamy?

#11: The Phantom of the Opera “Music of the Night”

What does it take to convince a total stranger to abandon her life as a ballerina above ground and hang out with a masked main in his underground lair? Let’s see how it works out!

Some final thoughts:

I hope this gives you a good start in preparing a lesson to watch, talk about, and analyze some great arguments in movies. As always, I’d love to hear about your experiences, ideas, and outcomes in the comments below! Which films did you use? Which films did your students best respond to? Happy analyzing!

FOR MORE RHETORICAL ANALYSIS PRACTICE:

LET’S GO SHOPPING!

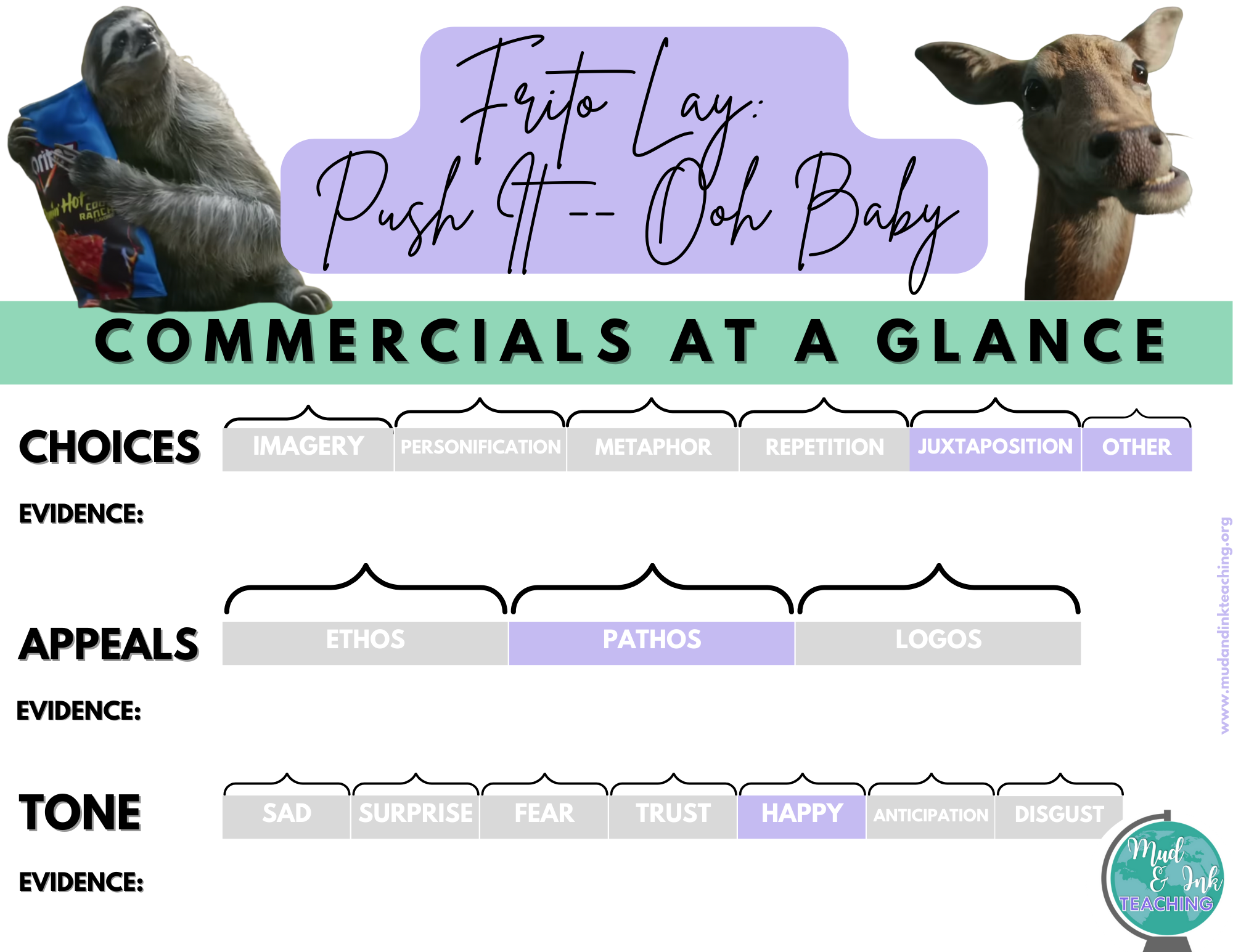

3 MORE Commercials for Rhetorical Analysis

Rhetorical analysis is a skill that needs practice and reinforcement all year long. Use this template and three commercial suggestions to help you get going with rhetorical analysis in your classroom.

There’s just something about commercials that make them such ripe teaching tools for practicing rhetorical analysis. The problem is, though, that it can be hard to find ones that are just right for students. In an effort to continue making more commercial rhetorical analysis ideas available to teachers, I’m stepping up my game and adding a few more to the conversation right here! Let’s jump in.

A FEW REMINDERS:

Before starting with ads, make sure you’ve covered the rhetorical situation. I have an easy and fun lesson for that ready-to-go featuring the song “Be Our Guest” from Beauty and the Beast, so feel free to use it!

You might also consider having your students familiar with SPACE CAT or another framework that you like (another might be SOAPSTONE). I dive into that a bit further with the song “Mother Knows Best” from Tangled and share a free rhetorical triangle template here, too.

If you like these commercial suggestions, you might also like this blog post with three Super Bowl ads from 2022 that is very similar to this post -- just more ads to put in your arsenal!

Rhetorical analysis is a skill that needs to be practiced over and over and over again. Too often, we are introducing ethos, pathos, and logos on repeat without ever getting much further. We know rhetorical analysis is so much bigger than labeling a few appeals: it’s about understanding the power of the message in the context that it’s delivered.

START WITH YOUR TEMPLATES

If you are new to the idea of using SPACE CAT or any other framework to guide your lessons, I’ve got you covered. When I teach RA, I like to try and consistently use the same kinds of handouts for every lesson so that students aren’t constantly learning a new way to “do” the job and I’m not constantly recreating the wheel. Here’s what I’ve created for you to try with your students:

On the one side, students are brought back to the rhetorical triangle and grounded in the rhetorical situation as much as possible. Some commercials are a bit tricky to deciper (as opposed to speeches or moment from film), but make sure they start with speaker and audience at the very minimum. Then, using these templates, students can dig into the argument itself and shade in the particular choices they notice, the appeals at work, and the tone word range that they observe in the commercial. This is a very basic starting point, but it serves as a visually clear way for students to try and see all fo the pieces of the argumetn working together AND prioritizes the use of evidence for each. You might not examine all three components every time, and that’s totally okay! Simply cross out what you’re not working on and focus on the rest.

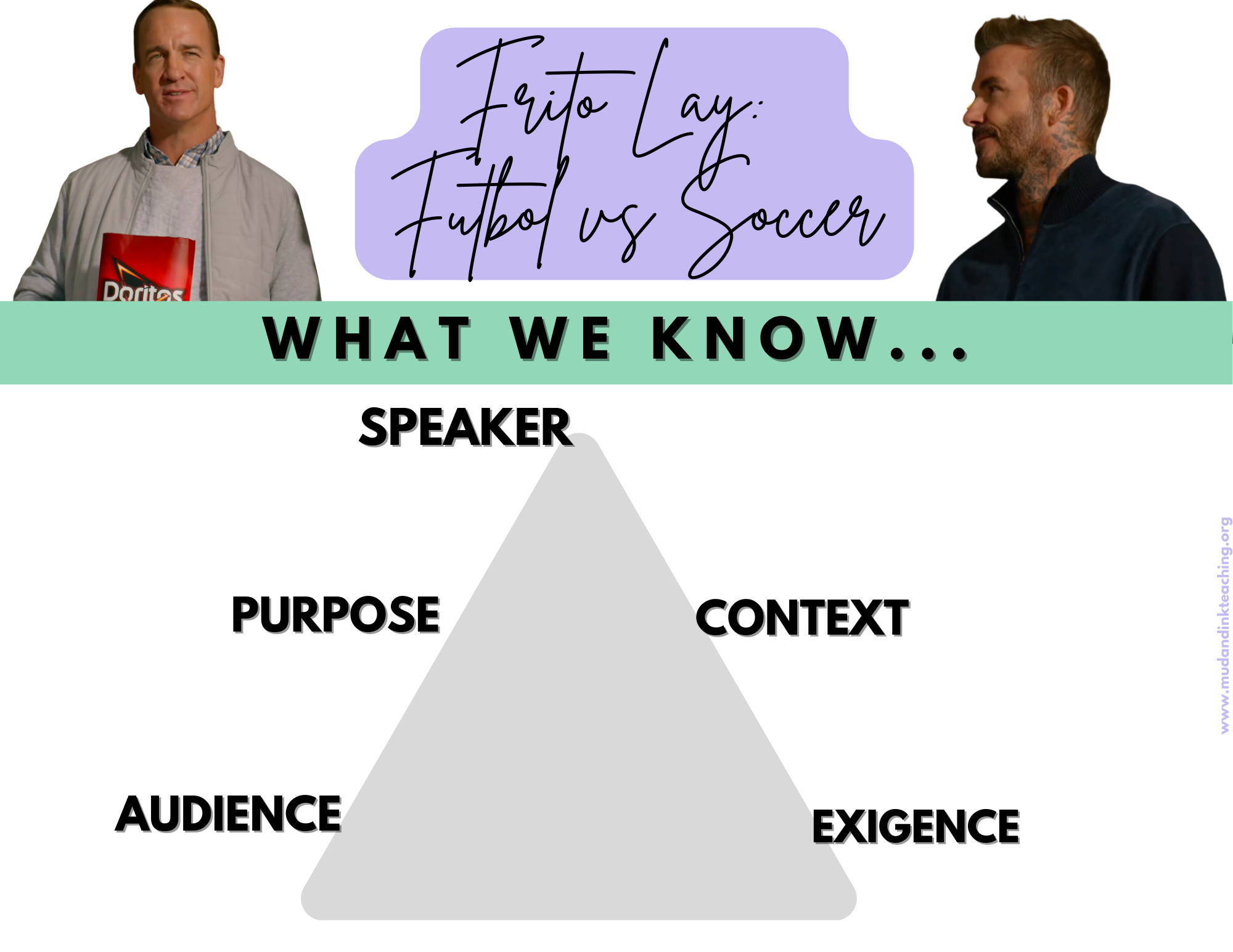

FRITO LAY: IS IT FOOTBALL OR FUTBOL OR SOCCER?

Up first is a chip commercial and a centuries-long debate: do we call it futbol or soccer? Featuring two huge celebrities (Peyton Manning and David Beckham), Frito Lay harnessed a playful moment of intersecting worlds during the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Here are a few places that are worth spending time in your lesson and analysis practice:

SPEAKER: We have TWO speakers from two seemingly polar opposite sides of the debate. What is each man known for? What makes each of them credible in their own expertise? What kind of personality do these men have and how does that translate into the tone of the commercial? Depending on which version of the commercial you watch, there are even more celebrities in the soccer/futbol world brought into the story to lend his or her own side to the debate, deepening the roots of the history of the question. Guide students to think about the circumstances for each of the celebrities -- they are especially important in guiding the tone of the ad (I mean, who doesn’t get tickled by Mia Hamm going off on a park district referee?!)

CHOICE: JUXTAPOSITION: Beginning with the two speakers, this commercial leans into the power of opposing forces to create humor, tension, and involve a vastly large audience. The most commonly juxtaposed images are that of ordinary, everyday soccer matches (mostly for kids) against massive stadium-sized matches with thousands of roaring fans. Beckham even jokes about the size of the World Cup as an insult to Manning’s/American football’s Super Bowl. The celebrity spokespeople are juxtaposed against each other or the other person they’re debating the word with (think Mia and the ref). And here’s the thing -- even though the opposing forces are strong, it’s FRITO LAY CHIPS that brings everyone together in the end. The brand is the unifying force, no matter which side of the debate you might find yourself on.

APPEAL: PATHOS: Largely, the inclusion of memorable celebrities (Brandi Chastain, Mia Hamm, etc.) and their playful banter aim to create an emotional experience of togetherness and unity. The commercial seeks to acknowledge a divide (playfully), but then warmly reminds the audience of their shared love for the world’s game. The brand is featured affectionately as a witness to all of these events and ultimately as the one thing that everyone can agree on.

TONE: The tone of this commercial fits anywhere in the light, happy, and even trustworthy side of the circle of emotions. Students could defend several tone word combinations, especially looking at the use of banter, sarcasm, and overall humor.

The All-New PlayStation Plus: Why be one thing, when you can be anything?

CHOICE: IMAGERY: The commercial begins in public, in daylight, in a diner. Slowly, the narrator moves from the outside world, into his home, and deeper and deeper into spaces inside that (presumably) the outside world never sees. The commercial is mostly dark and focused on these interior spaces that are sprinkled with the unexpected and fantastical (what was that fish in his fish tank?) As each scene (image) draws the audience deeper into the narrator’s home, we’re experiencing what Playstation is suggesting it must feel like to have this rich, inner life of fantasy and imagination through their gaming experience.

You might also talk about juxtaposition and the use of rhetorical questions, too.

APPEAL: ETHOS: While certainly the commercial is emotional in terms of the excitement and tension building around where on earth that huge slab of meat is going, it would be interesting to talk to students about how Playstation has also created a scenario in which they are the trusted brand to bring this kind of imagination to the audience. They’ve presented a fantastical scenario, one that many might feel envy or hope to experience themselves, and by dropping small hints of each of the games they’re best known for, they’ve also created a powerful sense of credibility as the providers. The layering of images from the various games works to develop trust that Playstation will give its players this incredible experience.

TONE: With a series of reflective rhetorical questions and a blurred line between reality and fantasy, Playstation has created a curiously inspired tone in this commercial. It’s a bit jarring and it’s a commercial that makes the audience wonder what just happened?. The placing of items such as the astronaut helmet in the closet leaves the audience trying to connect a series of dots -- they’re constantly wondering what’s coming next. This sense of curiosity and wonder reflects the experience that Playstation hopes its audience will have while playing their games.

FLAMIN’ HOT DORITOS & CHEETOS: “PUSH IT”

RHETORICAL CHOICE: Incongruity & Reversal: If this is the time to start talking bout techniques of humor and satire, you might consider placing these two at the table: incongruity and reversal. Before digging in, a quick reminder: “correctness” is less important than the critical conversation around deciding on a best choice. These two techniques are challenging, and the last thing we want to do is present something that add to the impression that rhetorical analysis is as simple as “device hunting”. That said, if this is part of a larger conversation about humor in rhetoric or satire in communications, this commercial would be great to use to flesh out the ways in which the commercial’s core technique would be considered incongruous or reversal. In this particular example, I think it’s helpful to have students focus on the subject rather than the characters: the Doritos and the Cheetos. How is the subject handled? When examined this way, I think a strong argument could be made for incongruity. I like the way ReadWriteThink breaks it down here if you’re looking for a reference.

APPEAL: PATHOS: The composition of the commercial is aimed at creating a comfortable and lighthearted relationship with the audience. The use of cute, animated jungle creatures? Adorable. The fun throwback song? So adorable. The look of surprise on the hiker’s face as the sloth drags away a bag of Doritos? So funny. The commercial relies on the absurd scenario to break down any defenses and create a memorable, humorous connection between the brand and the audience.

TONE: While there’s not much dialogue to dissect here, this is a great opportunity to have students look at tone through music. The popular song from Salt ‘n’ Peppa used here has been reduced to just a fraction highlighting the catch phrase -- what is the effect? How does it create such a humorous scenario?

Some final thoughts:

I hope this gives you a good start in preparing a lesson to watch, talk about, and analyze some great commercials. As always, I’d love to hear about your experiences, ideas, and outcomes in the comments below! Which ads did you use? Which ads did your students best respond to? Happy analyzing!

FOR MORE RHETORICAL ANALYSIS PRACTICE:

LET’S GO SHOPPING!

Teaching Rhetorical Analysis: Using Film Clips and Songs to Get Started with SPACE CAT

Try beginning your rhetorical analysis lessons by focusing on the rhetorical situation before heading into deeper analysis. When you’re ready, dig in using SPACE CAT and a great song from a musical that has a premise and an argument to examine. Here’s what we’ve done in my class using “Mother Knows Best” from Tangled.

Rhetorical analysis: so much more than commercials and appeals

Rhetorical analysis can get a stuffy reputation. Sometimes, we reserve it only for “serious” classes and students and we focus on monumental, world-shaking types of speeches. While this approach accomplishes a few of our long-term goals for education, it’s not doing enough to reach the masses of students who need these skills.

I hope you’re here reading this because you want to try RA with seventh graders. You want to introduce rhetorical analysis to your struggling 10th graders. I hope you’re here because you’re trying to do RA even though you haven’t been deemed worthy and been exclusively anointed as an AP Lang teacher. I hope you’re an AP Lang teacher here looking to do things with a broader scope and new entryways into conversations about complexity and sophistication.

Really, I’m glad you’re here.

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: THE BASICS

Here’s where we need to start: the triangle.

Rhetorical analysis is less about appeals and more about the unique connection between three points: the speaker, the audience, and the message.

When we start RA zeroing in on ethos, pathos, and logos, we are playing a bit of a dangerous game. Teaching terms can be a comfort zone for teachers (we do this with figurative language, too). In our field, there are so few direction instruction content types of lessons, that it can feel cozy to snuggle up with a list of terms we understand and deliver them to our students. Without realizing it, we’ve created a pretty deep hole, jumped in, and forgot to throw down the rope ladder for when we need to get back out.

When we start with terminology, we’re sending the message to students that this is the primary focus of analysis: identification. We’ve armed them with dozens of terms, so the goal of analysis must be to slap these labels all over a speech and call it annotation. Then? It ends. Students falsely believe that they’ve accomplished the task because they did exactly what you taught them. They found the rhetorical questions. They found a simile. They found an example of ethos.

And then? We get really frustrated when they can’t tell us WHY, HOW, or SO WHAT when we probe them deeper about what they’ve identified.

This is my very long way of telling you this: DON’T start with terms, or, if you do, be ready to pivot quickly!

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: WHERE TO BEGIN

START with the rhetorical triangle or a framework that you like (I like SPACE CAT) and a conversation around the rhetorical situation (SPACE). By emphasizing the importance of understanding the components of the broader context of the argument, we help students start the probing question why? in the back of their heads as we go deeper and deeper into the argument itself.

One of my favorite pieces to use for practicing the rhetorical situation is looking at Lumiere’s plea to Belle in “Be Our Guest”. In another blog post, I outline how much there is to the situation -- there is so much to consider in terms of the speaker, the purpose, the audience, the context and the exigence. In the slide deck for this lesson, we spend a great deal of time listing as many details as possible before even looking at a single lyric. Why? Because once we get into the argument, we’re seamlessly moving through true analysis.

Ms. C? I think I found a simile.

What similie is that?

Well it says ____________.

Hmm.. You’re right. So why does this particular simile hold weight knowing what we know about who Lumiere is and what he’s trying to achieve in this moment?

Wheels turning…

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: GETTING INTO THE ARGUMENT

So we’ve got a handle on the rhetorical situation. That’s a win. In fact, that might be the entire goal of a unit if you’re just beginning. If your school is taking their time and truly working on vertical articulation, this is a great skill to introduce at 9th grade and build toward mastery in 10th.

But let’s say we’re moving on a bit and ready to analyze the argument. You might have a speech, a commercial, another song, or another type of fictional scenario, and now we need to look at the techniques used and do the analysis work.

This is where we come back to our analysis framework. I like using SPACE CAT, so this stage is where I rely on CAT: choices, appeals, and tone.

Rhetorical choices include just about everything, so it’s up to you to narrow the lane of what each argument is doing well. A rhetorical choice might be the structure or organization of the argument, an extended metaphor, the use of personification, or even a particularly interesting use of parallel structure. Appeals are what you think they are: ethos, pathos, and logos. And of course, tone is exactly what you think it is, too.

Not all choices, appeals, or potential tone words are important to talk about in every speech, so fully embrace your right to decide ahead of time which choices are on the table for discussion (this is called scaffolding and if you need help with it, I have a training in my Mastering Close Reading Workshop that you might find very helpful!).

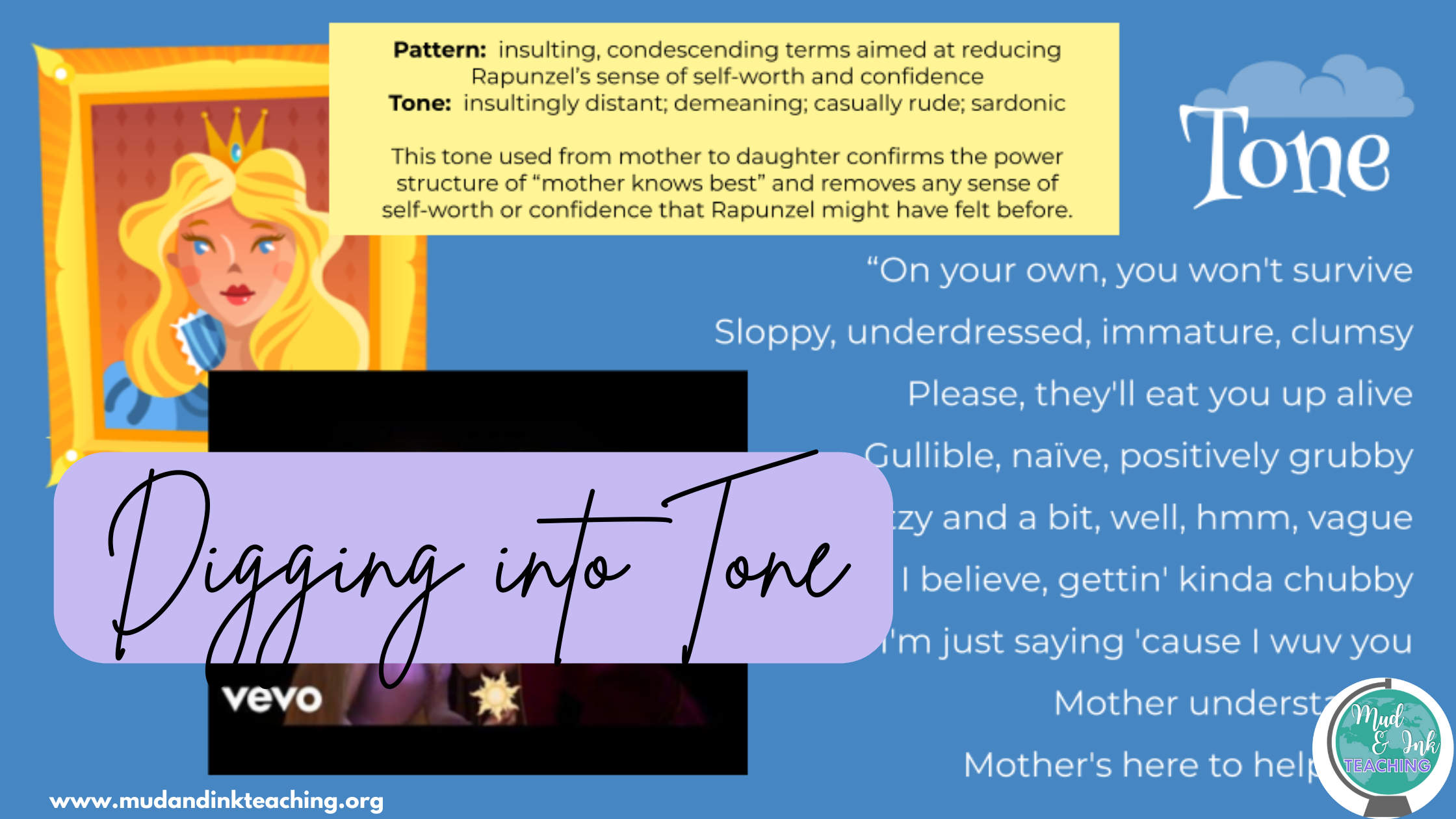

Let’s Look at an Example: “Mother knows best”

Here’s a quick example from “Mother Knows Best” in Disney’s Tangled for each of the components in CAT.

Mother Godel opens her song referring to Rapunzel “as fragile as a flower; still a little sapling, just a sprout”. She’s comparing Rapunzel to an undeveloped, extremely young plant.

She then uses the refrain “Mother Knows Best” along with other overly-assertive physical behaviors to assert her own ethos and Rapunzel’s lack of life experience.

The song also gives students the chance to look at tone, especially in the verse where Mother Godel tells Rapunzel that she won’t survive as a “sloppy, underdressed, immature, clumsy” and “gettin’ kinda chubby” girl out in the real world. This demeaning tone further underscores Mother Godel’s authority and increases the fear in Rapunzel about leaving her tower.

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: SO WHAT?

Well, we’ve arrived back where we started, friends. There’s a whole lot of highlighting, lots of phrases and details identified as one thing or another, but here comes the real work: SO WHAT?

So, Mother Godel uses a demeaning tone toward Rapunzel. So what?

She compares her to a “sapling” that has just sprouted from the ground. So what?

Here’s where we send students back to the rhetorical situation.

Support them through their “so what” with questions referring back to SPACE:

Why is this tone effective given what we know about the audience?

How does this metaphor create a sense of fear in Rapunzel?

How does Mother Godel’s use of hyperbole help her achieve her purpose?

Given the context of the situation, why would Mother Godel rely on the emotion of fear in this particular argument?

Once you’ve gotten through the SPACE, the CAT, and now arrived at the analysis part, remember that you can do this a few ways. Students oftentimes will write a paragraph of analysis, but if you’d prefer, you might have students complete a one-pager or just have a discussion that outlines what students could write about. It’s okay for some lessons to be heavier on the process than on the result.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS…

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS: TRUST THE PROCESS

This is the process. It takes time, practice, and more practice. But if you are able to confidently lean on a framework that you like, provide the right types of arguments that meet students where they’re at, and stretch their work with rhetoric over multiple years, you’re going to find increasing success.

If you’re looking for more support, I have resources that are ready to help you. Keep doing the work -- I’m right here behind you every step of the way.

LET’S GO SHOPPING…

3 Super Bowl Ads to Analyze for Rhetorical Analysis

Rhetorical analysis is a skill that needs practice and reinforcement all year long. Take a break from what you’re doing and tackle these Super Bowl ads together for students to practice discussion and analysis in an entertaining and engaging lesson.

Note to readers: This post was written prior to the 2022 Super Bowl in an effort to help teachers pre-plan their lessons and not have to wait until the Sunday night after the game. The ads suggested in this posted are based on the year 2022 and what was pre-released ahead of the game. There are dozens MORE commercials to use as powerful teaching tools, and you can access our public Wakelet for more ideas here! Happy reading!

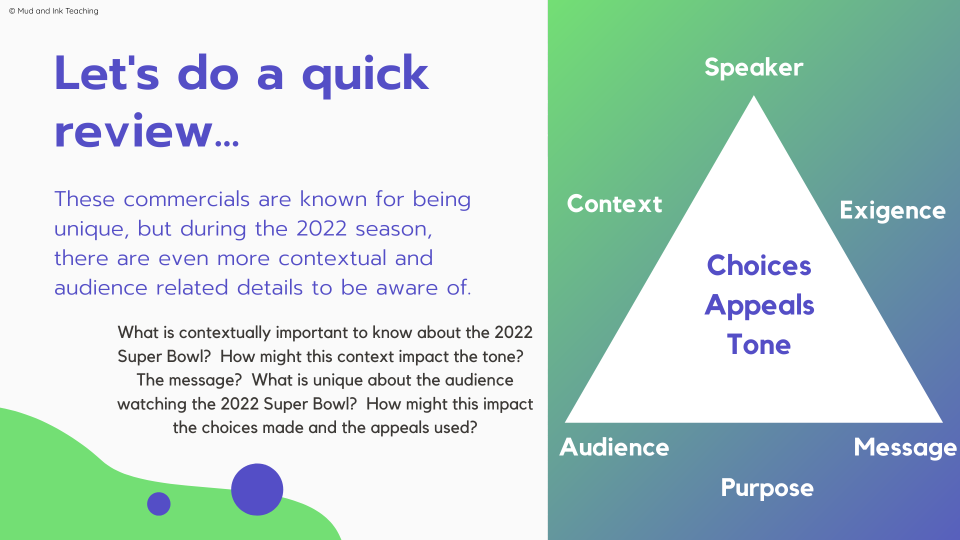

Rhetorical analysis is a skill that needs to be practiced over and over and over again. Too often, we are introducing ethos, pathos, and logos on repeat without ever getting much further. We know rhetorical analysis is so much bigger than labeling a few appeals: it’s about understanding the power of the message in the context that it’s delivered.

START WITH THE RHETORICAL SITUATION

If you are new to the idea of the rhetorical situation, fear not! I have you covered. For a basic overview for yourself AND a lesson for your students, I highly recommend checking out the article I wrote that shares the lesson I do with my students on the song “Be Our Guest” from Beauty and the BeastI. Go check it out here:

When it comes to Super Bowl ads, the rhetorical situation is just as important as figuring out what rhetorical strategies are in play. Students need help identifying the speaker (is it the company or the actor?), recognizing the different purposes of advertising on this specific day (hint: it’s not always to sell!), and getting a stronger grasp on the intended audience (students think they are the audience just because they are watching the ad. Think again, kids!). Students may have never considered the value (yes, I mean $$) of building brand loyalty or the cultural relevance of patriotic imagery.

Super Bowl ads taught in a group give us the instructional power to discuss context in a powerful way: these ads are so highly reflective of the climate of the country at the time, and this provides a powerful place to discuss the themes and trends that students are seeing in the ads. For example, Stacy Jones from Hollywood Branded predicts, “Some of the overarching themes to Super Bowl ads this year are going to be adventure, growth and pushing yourself to expand past your boundaries. We’ve been in a lockdown for two years, with people busting at the seams to get out and experience life and live. Brands and the people behind them feel the same—and they’re ready to help fuel the adventure.” These are prime conversations to have with students — and ones that will be highly engaging for them.

HYUNDAI: JASON BATEMAN ACROSS HISTORY

Up first is a car commercial: The Hyundai Ion 5, an electric car that promises to be a necessary advancement in the evolution of driving. Here are a few places that are worth spending time in your lesson and analysis practice:

SPEAKER: If we say that the speaker here is Jason Bateman, then we have an interesting conversation ahead. What is he known for? What types of shows and films is he in? Why would Hyundai choose him as their spokesperson? What credibility might he add to their brand?

AUDIENCE: Now that we know more about the speaker, what does that tell us about the intended audience? What kind of an audience would connect with Bateman? What kind of audience might be interested in this product? Think about: age, gender, social/economic status. Are those people likely to be watching the Super Bowl?

TECHNIQUE: ANAPHORA: The commercial uses a repeated phrase (anaphora) for each example of ways that we have evolved in our technology across history. This is a great opportunity to talk about the effectiveness of its use and how that connects to the overall purpose of the ad.

AT&T: ZAC EFRON FISHING

SPEAKER: If we say that the speaker here is Zac Efron (both speakers, actually), how does that affect our analysis? What is he known for? What types of shows and films is he in? Why would AT&T choose him as their spokesperson? What credibility might he add to their brand? Why might they have him dressed this way and out in nature?

AUDIENCE: Now that we know more about the speaker, what does that tell us about the intended audience? What kind of an audience would connect with Efron? What kind of audience might be interested in this product? Think about: age, gender, social/economic status. Are those people likely to be watching the Super Bowl?

TECHNIQUE: HYPERBOLE: The hyperbole of this commercial is used in layers. Each hyperbole is visually stacked on top of another. How do these hyperboles contribute to the tone of the message? What do they reflect about the service provided? How might these hyperboles be read by the intended audience and how might that impact the success of the message?

CHEVY SILVERADO: WILDERNESS CAT

SPEAKER: This commercial does not use a well-known celebrity, and instead, a relatively unknown male actor. What do we know about this speaker’s demographics? How do these overlap with the intended audience? Why might that have been an important consideration for Chevy when casting this ad?

AUDIENCE: Based on what we know about Chevy and pickup trucks (and even the setting of the commercial) what kinds of people tend to be targeted by this brand? Are these people watching the Super Bowl? Is the 6+ million dollar investment likely to reach the intended audience?

TECHNIQUE: INCONGRUITY: Incongruity is a satirical technique that this commercial employs when the opposite of what’s expected is present (this can also be discussed as irony). Seeing a gruff man in the wilderness with a pickup truck, the audience expects him to have a dog by his side. Instead, it’s a cat. What is the effect of this incongruity? What kind of tone does it help create? How does this come back to the product itself and the intended audience?

I hope this gives you a good start in preparing a lesson to watch, talk about, and analyze some Super Bowl commercials this year. As always, I’d love to hear about your experiences, ideas, and outcomes in the comments below! Which ads did you use? Which ads did your students best respond to? Happy analyzing!

FOR MORE RHETORICAL ANALYSIS PRACTICE:

LET’S GO SHOPPING!

4 AP Lang Skills ALL Students Should Learn

AP Language and Composition shouldn’t be the only place where students learn certain skills. In fact, these skills are so important, they should really be spiraled down into all of the grade levels leading up to Lang. Here are my top four recommendations to consider in your vertical articulation in your English Department.

I am a firm believer that any student who wants to take AP Lang and feels adequately prepared for the challenge should be allowed to take the class. That said, I spent the majority of my career in non-AP classrooms, and didn’t really know what was going on behind the AP curtain until I went to my first APSI (Advanced Placement Summer Institute). There are so many things that I’ve witnessed beginning Lang students struggle with that could easily be worked on and developed in the courses leading up to it. If you’re in a place in your career and curriculum writing journey where you’re looking to make some adjustments that help increase purposeful rigor, here are the skills to focus on.

This blog post is written in collaboration with Dr. Jenna Copper who has written her post on this same topic, but with a focus on preparing students for AP Literature. Between our two posts, you’ll have your students more than ready to embark on their AP journey in their English courses!

RHETORICAL ANALYSIS

Sometimes it can feel like there’s only time to practice analysis during summative writing assignments. If we truly want to see students grow in that area, however, we must create more opportunities within units to let students practice true analysis: discovering how the pieces of a text work together to create a whole. In AP Lang, this is done almost exclusively through nonfiction and other types of media that showcase an argument.

Rhetorical analysis is worth tackling at the younger grades, and I mean spiraling those skills beyond defining ethos, pathos, and logos. When we introduce rhetoric as a concept without the skill of analysis, there’s a lot of backtracking that needs to happen. Rhetorical analysis is not just identifying the parts (labeling ethos, pathos, logos, personification, etc.) but connecting those pieces together to figure out how they impact, shape, and build an argument.

My favorite way to introduce rhetorical analysis to students is not by showing commercials and defining the appeals. Instead, I introduce the rhetorical triangle, the argument as a whole, using a song. “Be Our Guest” from Beauty and the Beast is the perfect example of the rhetorical situation and the rhetorical triangle. Why would Lumiere use humor at this moment to convince Belle to stay? Why would he flatter her? Why would he establish his reputation as an excellent host? These “why” questions take students away from identification and toward analysis from the start. I wrote all about it and have a free sample lesson in this blog post!

I’ve even had fun (gasp!) with students practicing rhetorica in a low-stakes gameshow that I like to call: The Spare Change Gameshow. Students are faced with fun, friendly prompts and have to practice building their argument based on whichever rhetorical skill we are working on at the time. You kids will love this, and all you need is some spare change!

BUILDING / TRACKING A LINE OF REASONING

If you’re unfamiliar with the term “line of reasoning”, that’s okay. It’s a relatively new term, but it's something we’ve been teaching in writing for a long time. A line of reasoning is the thread that connects the most important structural pieces of an argument together: the thesis, the subclaims, the transitions, and all of the commentary that explains the connections that you are assembling with these pieces.

When introducing this as a concept (this is assuming students already know that there is a connection between their claims and subclaims), is through socratic seminar and fishbowl discussions. I present students with a big question and let them start tackling it. I map their conversation as they speak, tracking the beginning idea, the supporting comments, the changes in direction, the jumping off in a new direction moments, and then, I show it to them. I show them a sketch-noted, mapped conversation and discuss the line of reasoning from an initial claim to where we ended up. Discussions are messy and reading this map is often a bit confusing, but that leads us directly into a conversation about successful writing. Effective, written arguments are not the same as casual, organic conversation. Both have a line of reasoning, but the written one, the one that they are charged with completing, must have a carefully organized plan so that line of reasoning is clear, coherent, and persuasive. Our discussions eventually get somewhere deep and meaningful, but there are a lot of distractors along the way. By making this concept both an experience and something tangible they can see and hold, it helps students start to wrap their heads around this concept.

USING EVIDENCE

Teaching students to use evidence is just as important as teaching them to find evidence. Using evidence is where we find students struggling, and this directly links back to my previous two points: practice with analysis and the line of reasoning.

Accumulating some effective sentence frames is a great way to help beginning writers do this. Also, I’m here to let you know that it’s okay if the phrases used to present their arguments are less than desirable. I know that “this quote shows” is pretty annoying, but if that annoying phrase helps students get to the analysis part of that sentence, LET IT GO. Sometimes, phrases like this are just little bridges that help students get from the evidence to the commentary and analysis, and the more we harp on what phrases NOT to use, the more time and energy students spend on phrasing rather than attacking their arguments.

Coaching them with alternative options helps them get better. Instead of getting riled up, offer them frames like this:

The repetition of the word “_____” in this sentence is an indicator of the tone shifting from __________ to _________. At first the language was ________, but then the speaker starts repeating “_______” changing the energy of the conversation to ________________.

By using a (adjective) type of imagery here, the speaker reveals ___________.

Despite ______________, the speaker still argues _______________ in this line. This is important to note because _______________.

We even do this kind of practice in something I call a “paragraph chunk quiz”. On my podcast, Marie and I talk extensively about using sentence frames for formative assessment in our Masterclass: Down with the Reading Quiz.

CLOSE READING (FOR A PURPOSE)

Oftentimes, our English classes at the younger levels get bogged down with time spent clarifying plot points of the novel we’re reading in class. Monitoring students as they follow reading calendars and making sure they’re on pace is a trying task. But here’s where everything changed for me: shifting my priority to close reading.

The key to effective close reading lessons? A focused, limited purpose. When we read A Raisin in the Sun Act 1 Scene 1, we spend an entire class period close reading the Ruth and Walter scene where they fight about eggs. We watch the evolution of the eggs, the mentions of them and how they shape the tone and energy of the conversation. We walk away from that one day, that one, tiny moment of text, with a deep, layered understanding of the relationship between these two characters. Students are able to write about what the eggs symbolize and practice the skills we’ve been talking about here (analysis, using evidence) because we’ve been nose deep in the moment. You can take a look at all of my Raisin resources right over here!

By having close reading templates on hand, I can create these lessons quickly and effectively. Whether you can practice close reading with nonfiction, within novel units, with poetry, or other pieces, this is a powerful strategy to regularly use in preparing students to be stronger readers and writers as they move up in their English Language Arts journeys.

For more tips and ideas, be sure to check out Jenna Copper’s post in our collaboration between AP Language and AP Literature.

5 Common Mistakes Teachers Make When Teaching Figurative Language

Raise your hand if the first unit of your school year is a short story unit with figurative language terminology review? Yes? This is unit one in thousands of English classrooms and this makes me wonder…if they’ve done this so many times, why aren’t they experts? How is it that by unit 2, the next time we encounter an example of personification, they’ve forgotten the term altogether?

The thought process here is logical: provide terms, provide definitions, provide examples, practice, practice practice = learning has succeeded. But we see this doesn’t actually happen. So what’s not working?

I want to be very honest about this: I struggled writing the title of this article using the word “mistakes” because I don’t want teachers to feel like there’s one more thing I’m doing wrong. That’s not the heart of this at all. And let’s be perfectly clear: I’ve made ALL of these mistakes MULTIPLE times, and the reason I’m writing this now is that time, experience, training, and more experience have taught me more effective ways to do a part of our job. I wish I would have recognized these things about my attempts to teach figurative language earlier in my career. It would have prevented me from a lot of self-doubt and helped me grow my students into much more critical thinkers.

None of these “mistakes” are harmful to students. And if you’re finding these methods to be highly effective for your population, by all means, keep it up! But if you’re feeling like this is the 1,000,000,000th time you’ve tried to get kids to define “metaphor” and it’s still not sticking, stay with me.

Let’s start with our WHY

Always start here. Why do we teach the terminology, examples, functions, and use of figurative language in literature and poetry? For me, it boils down to a few important things:

These devices create an intentional effect. Analysis of the effect is important in understanding the message, the purpose, and the experience the audience is supposed to have.

These devices contribute to character development. If we value character complexity and development, being sensitive to the nuances in the details authors use to describe them requires an understanding of figurative language.

Many of these literary devices overlap with our study of rhetoric. Recognizing the tone of a particular metaphor or simile used in a speech, commercial, or other argument is important, so it’s highly valuable that this practice overlaps into two skill areas.

ONE: Rote Teaching Terminology (in isolation and otherwise)

Raise your hand if the first unit of your school year is a short story unit with figurative language terminology review? Yes? This is unit one in thousands of English classrooms and this makes me wonder…if they’ve done this so many times, why aren’t they experts? How is it that by unit 2, the next time we encounter an example of personification, they’ve forgotten the term altogether?

The thought process here is logical: provide terms, provide definitions, provide examples, practice, practice practice = learning has succeeded. But we see this doesn’t actually happen. So what’s not working?

Well, the first issue here is that language isn’t logical. And what we actually end up seeing is that the amount of time and energy we place on learning terms tells students that this is the most important part of the process. We know this is not the case (go back and look at our WHY), but in our teacher minds, we think: if they can’t identify a metaphor, how can they ANALYZE a metaphor?

I use to think this too. But then, after an Advance Placement Summer Institue, I was convinced to let go of terminology and see what happened. While close reading chapter 1 of The Great Gatsby students pointed out this line: “Two shining, arrogant eyes had established dominance over his face and

gave him the appearance of always leaning aggressively forward.” The students noted the use of the phrase “arrogant eyes” and debated how it should be identified. Was it personification? Eyes are a non-human object and certainly can’t possess the human trait of arrogance. Was it diction? Specific word choice Fitzgerald was using to create an effect?

I interjected and asked, “Tell me this: if you didn’t have to label the device Fitzgerald is using here, what would you say about this phrase anyway? Or if I told you that both labels work equally well, what do you have to say about the effect they have on characterizing Tom?”

I realized in this moment how little the term actually mattered. What mattered was that they did identify a critical description of a character. Call it diction, personification, description, connotation — that didn’t really matter in the end. But what I also realized is that students who get stuck here at this step, choosing the right term, would rarely make it to the next (and much more important) step of analyzing how this orients the reader to Tom’s character.

Releasing the pressure off of students to "correctly” identify figurative language terms might just help us move the conversation into the harder task. I give you permission to take your hands off the wheel a bit and instead of drilling them with terms, give them a word bank. Build a class website full of rich beautiful examples that you see all throughout the year. Correct students when an interpretation is completely off, but only when it has prevented them from accurate and thoughtful analysis.

NEED HELP KEEPING THE BIG PICTURE IN MIND? YOU NEED AN ESSENTIAL QUESTION AT THE HEART OF YOUR UNIT.

THE ESSENTIAL QUESTION ADVENTURE PACKS ARE HERE TO HELP.

TWO: Assessing Definitions

Let’s go back to our WHY again: if the goal of teaching figurative language is to move students toward rich analysis, then what does assessing definitions do to help us reach that goal? Let’s look at these two definitions as an example:

EXTENDED METAPHOR: a metaphor introduced and then further developed throughout all or part of a literary work, especially a poem

SYMBOLISM: the practice of representing things by symbols, or of investing things with a symbolic meaning or character.

By definition, these two devices seem to have clear differences but put into practice, students have some good questions about the blurry line between the two. In Julia Alvarez’s novel In the Time of the Butterflies, the butterfly serves as an extended metaphor (or is it a motif?) throughout the novel. Students asked me every year, “But isn’t the butterfly a symbol for the girls and the rebellion?” And year after year I carefully explained that metaphor was a better term to use because metaphor requires comparison whereas a symbol is more of a stand-in. The layers of meaning are comparative to the sisters and their experiences and metamorphosis as they grow into rebels.

The famous “Green Light” of Gatsby’s world is a symbol, though. It’s an object that pretty much means the same thing throughout the text and represents a wide variety of interpretations of ideas and emotions for Gatsby.

So here’s the mistake I realized I was making: this level of understanding how language devices function, especially in long works (as opposed to poetry), cannot be assessed by asking kids to define terms. Also, as outlined above in Mistake One, does it really matter? Does it really matter if a student discusses the butterfly as a symbol instead of a metaphor? Or the Green Light as an extended metaphor instead of a symbol? If the analysis in the sentences that come after are spot-on, insightful, accurate, and lined up with the rest of the work, I think we should let it go. I’d rather spend time here, in the text, having hard conversations, than reviewing terms or assessing students on the definitions of terms.

THREE: Teaching Too Many Terms

If you’ve ever bitten off more than you can chew, you’re in good company here. I am notorious for getting super excited about a poem or a book and trying to teach ALL THE THINGS. My excitement and enthusiasm will make the kids engaged, write?

Oof. I couldn’t be more wrong. Too many terms in the lesson or even in the unit is a recipe for disengagement and burnout. This happened to me often with close reading things like Shakespeare or even other types of poetry. Repetitiotition here! Metaphor there! Synecdoche here! Allegory everywhere! Crash and BURN.

FOUR: FORGETTABLE EXAMPLES & Lack of “Flashbulb” Moments

If you haven’t yet read Keeping the Wonder, then maybe you haven’t stumbled across the concept of a “flashbulb” moment or memory. The authors write, “When we think about the moments that stand out in our memory, it’s clear that our minds hold onto the unusual or unexpected. By tapping into students’ innate curiosity, you can design memorable, meaningful learning experiences that captivate their interest and ignite their imaginations.” (Keeping the Wonder, 2021)

This concept is vital in our instruction of particularly important literary devices. I found that when I was scraping for examples to teach definitions or make flashcards on Quizlet, the examples were often unoriginal and oversimplified. Slowly but surely, I started building up a bank of device examples that were so powerful that they were unforgettable. My favorite flashbulb literary device lesson was in teaching juxtaposition, of all things.

This was our juxtaposition flashbulb moment: the ballet scene from The Phantom of the Opera. I haven’t taught the film in a long time, but the memory of this juxtaposition lesson is still crystal clear all these years later. I even get Facebook messages from former students every now and again about this, and it cracks me up! In the scene, the Phantom is chasing the stagehand (who knows too much) back and forth across the rafters of the stage. Below them, a spring ballet, complete with sheep, goats, and baby’s breath, is underway. As the Phantom closes in on his victim (darkness, impending death), the ballet swiftly picks up pace (spring, light, and full of life). The scene ends with a shocking murder of the stagehand, giving students the perfect moment to examine WHY the juxtaposition as an artistic decision works in the scene.

Trigger warning: This scene ends with a hanging

The success of this moment, of slowing down and spending almost two class periods on one literary device (which was not the original plan, by the way!) taught me, once again, that less is more. Did I cram through a huge list of lit terms that year? No. But did my student have a life long impression, memory, and deep analysis practice with one challenging device? Yep. And we still remember it.

FIVE: Missing the Structure of Spiraling

Vertical alignment might be one of the biggest struggles for English departments across the globe. In the coaching work I’ve done with schools, I’ve found that the single-most source of frustration for teachers is that they don’t actually have a hold on what students learned before they got to them or where exactly they’re headed after their class. Teachers crave autonomy, and rightfully so, but autonomy can quickly lead to isolation and problems with skill-building.

The instruction of literary devices and figurative language analysis should ideally be spiraled across grade levels with intentionality. When grade levels select texts, standards, and essential questions are built in curriculum design, this is a layer to consider adding. Here’s an example of what that could look like and figurative language focal points that would work nicely:

FRESHMEN:

Metaphor: Long Way Down

Imagery: Children of Blood and Bone

Point of View: Frankenstein

SOPHOMORES:

Juxtaposition: The Phantom of the Opera

Extended Metaphor: In the Time of the Butterflies

Personification: Fahrenheit 451

JUNIORS:

Symbolism: The Great Gatsby

Paradox: Macbeth

Parallel Plot Structure: A Thousand Splendid Suns

SENIORS:

Allegory: The Life of Pi

Point of View: Homegoing

Flashback: The Handmaid’s Tale

Clearly, these aren’t the only things that each particular unit would cover, but having in mind the flashbulb memory opportunities that naturally exist in each text helps spiral the skills. Now, each teacher knows where each of these devices is highlighted (we’re not skipping everything else, just giving extra attention to these each year), and can align their expectations of students accordingly.

LET’S GO SHOPPING

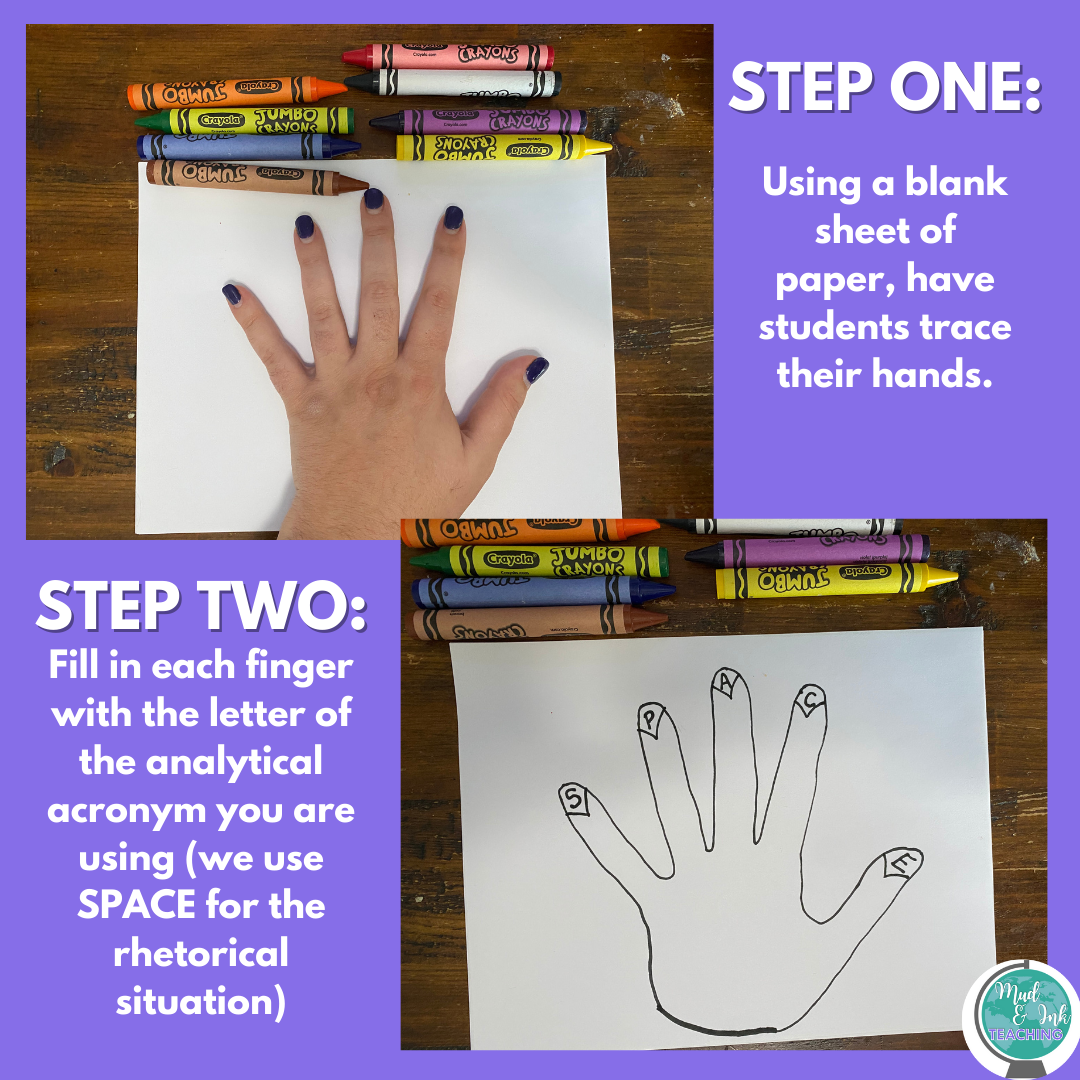

Rhetorical Analysis: A "Hands-On" Approach

Keeping rhetorical analysis fun isn’t easy, but here’s a simple idea that requires no extra work on your end. Handprint or five-finger analysis is a memorable and creative way to analyze an argument and you can easily customize this organizer to fit any season or text you are studying.

Is it a pre-requisite that all English teachers tell bad pun jokes? I mean, I just couldn’t help myself when I was giving this article a title. Let’s get right to it.

Rhetorical analysis. Whether you’re introducing at the younger grades or a seasoned pro at AP Language and Composition, we all get to a point in the year when RA feels like a bit of a chore. There are only so many Disney lessons we can do before we need to really get down to the hard stuff, so what's a great way to shake things up without sacrificing rigor? Bust out the art supplies.

This is not the first time I’ve taken an analytical practice and attempted to make it more tactile (here’s where we made sensory bottles to imitate tone in poetry and Gatsby), and that’s because I’ve learned my lesson: IT WORKS. Moving an analytical, thinking task to a tactile experience is exactly what helps kids continue to push their skills and avoid burnout and boredom.

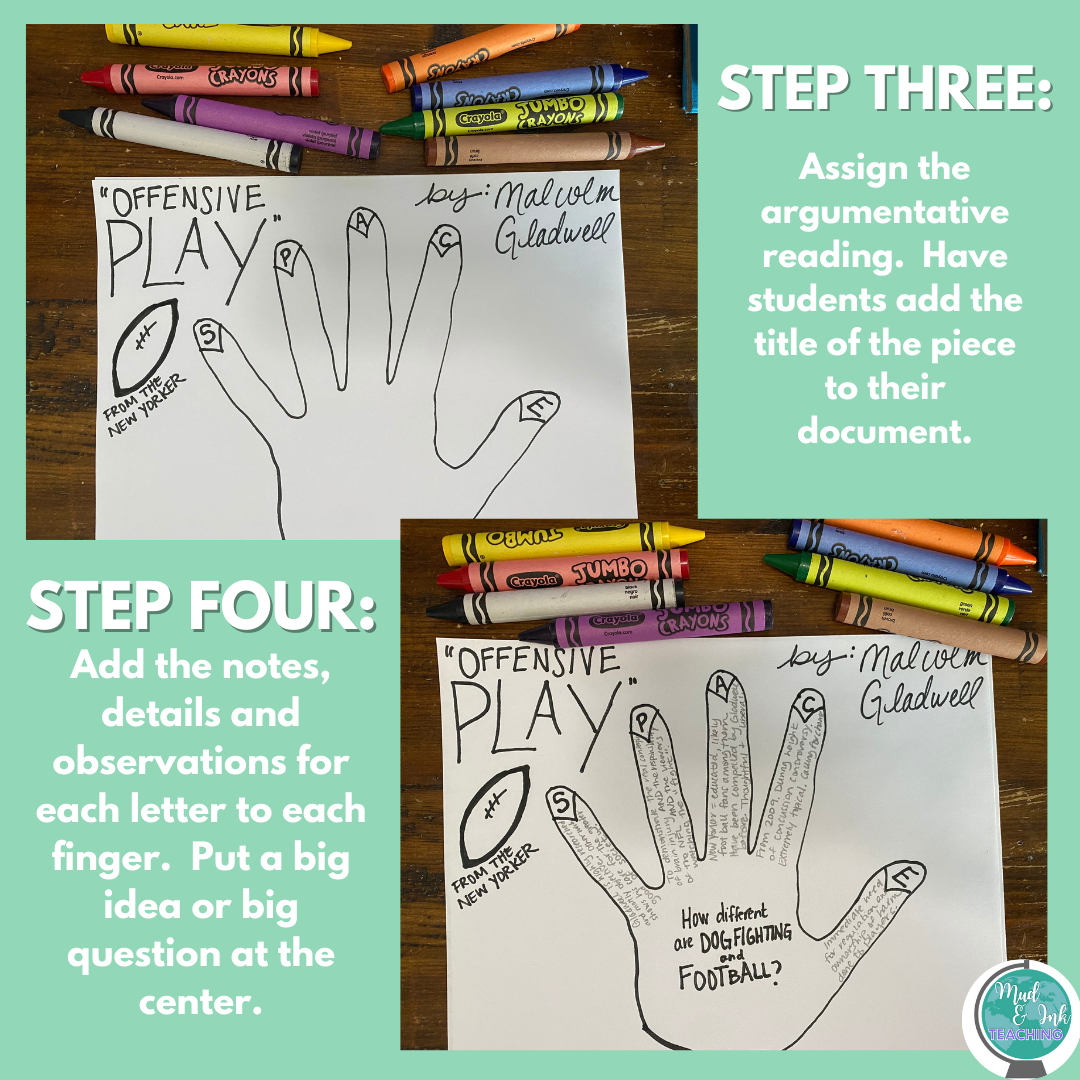

THE HANDPRINT ANALYSIS / FIVE FINGER ANALYSIS

Here’s what you’re going to need:

An argument to analyze

A previously taught & practiced acronym used for analysis (I like SPACE CAT)

A hand

A blank 8 1/2 X 11 sheet of paper

Coloring supplies (optional)

That’s it! I promised this would be low-maintenance.

And it works pretty much how it looks:

Assign an article, speech, commercial, or other arguments

Have students trace their hand on the blank page

Assign a letter of your acronym to each finger. If you’re using SOAPSTONE, you might need to use two hands or put some of the letters on the outside of the hand. I like to use the SPACE portion of SPACE CAT to practice the rhetorical situation. If you wanted to have students continue the analysis, they could add the “CAT” portion to the inside of the hand or the margins around the hand if you’d like.

Ask students to take appropriate notes in each of the fingers.

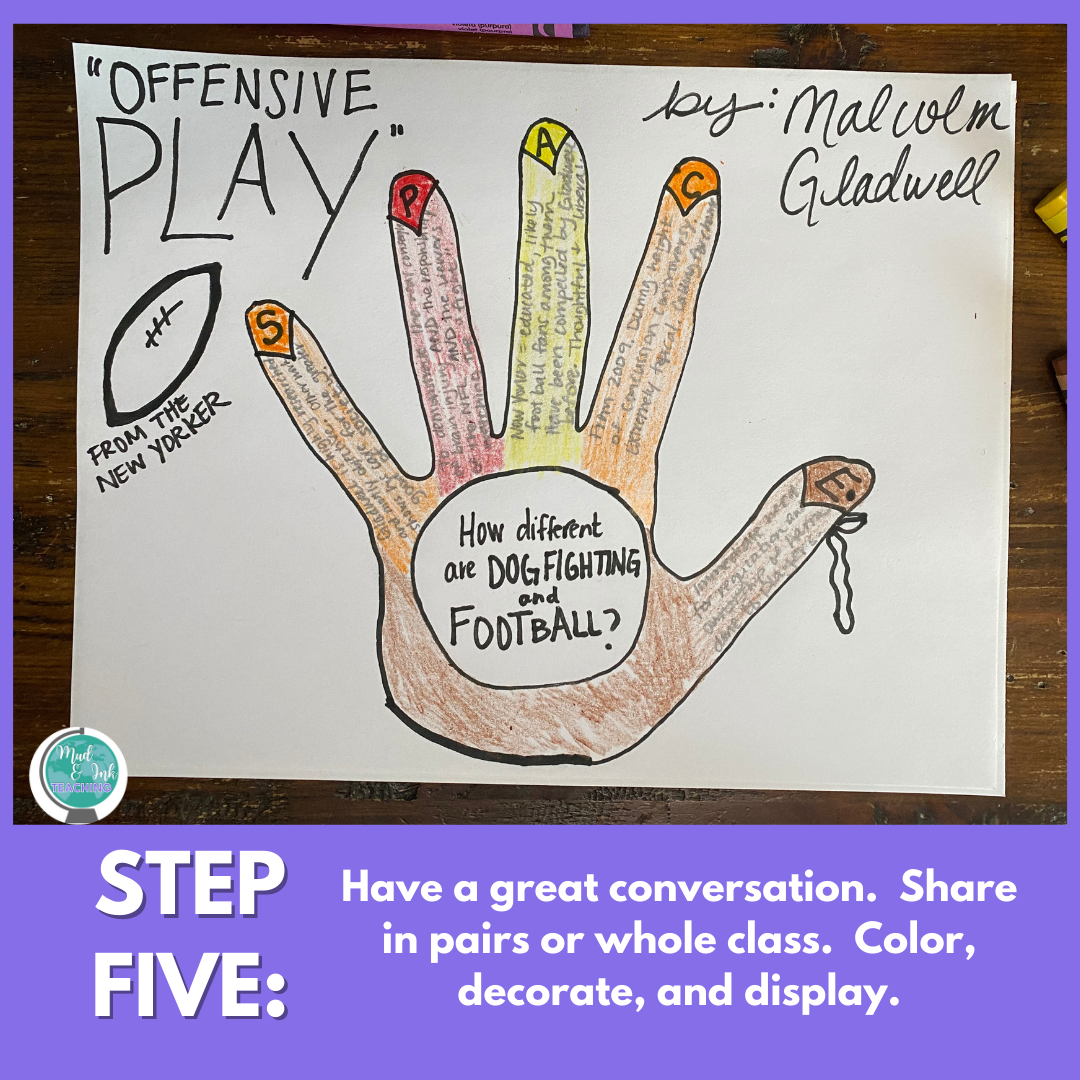

Teach your lesson as usual with sharing, discussing, etc.

Finish off the hand-outline with a seasonal turkey (if it’s that time of year) or simply have students color the hand into some other kind of animal or object that they desire.

Display proudly.

These kinds of activities are gold for you as the teacher. You are doing and practicing NOTHING NEW, but by changing the organization and appearance of the lesson, you will breathe new energy into your week and your students will keep giving you great work.

THANKSGIVING / FALL ARTICLES & READINGS

As I’m sharing this in mid-November, I’ll share some articles and pieces that work really well at this time of year. This activity is a wonderful pre-Thanksgiving break assignment and I’ve had a lot of success with the following readings:

“Offensive Play” by Malcolm Gladwell (Thanksgiving and football are a classic combination, but after reading this article, your students will have a whole lot more to say at the dinner table about dog fighting)

The President's Thanksgiving Day Address to the Nation from Lyndon B. Johnson (1963) A Thanksgiving message delivered only days after President John F. Kennedy was killed.

Why I’m Not Celebrating Thanksgiving This Year (VOGUE) A thoughtful piece from an indigenous woman’s perspective: what are we actually thankful for?

The Dark Side of Black Friday Stuff your belly and head to Best Buy to get in line…

However you use this activity and at any time of the year, I hope this brings a little life to your classroom without a lot of planning or prep on your end. If you try this activity, please tag me on Instagram @muandinkteaching to let me see how it went for you and your students!

And if you’re new here or new to teaching rhetoric and the rhetorical situation, I’ve got you covered. I’d love to send you a full lesson plan on how I introduce rhetoric using “Be our Guest” from Beauty and the Beast! This lesson has been downloaded by over 2,000 teachers! Good luck with your teaching rhetoric journey — its a worthy endeavor and I applaud you for your efforts!

LET’S GO SHOPPING

How to Use a Makerspace in the ELA Classroom

If you aren’t familiar with a makerspace, it is a place where students can create, problem solve, and collaborate. One of the greatest benefits of implementing a makerspace is that it shakes things up from your normal routine. It gives your students the chance to get silly and creative while giving you the gift of seeing your kids in a totally different light. Not only does it foster learning through inquiry, but it also helps to build overall classroom community.

The Makerspace. A place for all the STEM teachers and students, right? WRONG! A Makerspace is something I couldn’t fully wrap my head around as an ELA teacher at the beginning, but after a few ideas (attempts and failures), I found a few things that helped me embrace the messy, hands-on possibilities for my ELA classroom.

If you’re more of an auditory learner (or you just don’t have time to read because you’re on your way to school!), you can listen to my ideas on the Brave New Teaching podcast on Episode 64. Find us on iTunes or right here to listen to the full episode!

If you have a bit more time to read, then here’s the slightly longer version…

As the great Ms. Frizzle says, take chances, make mistakes, GET MESSY!

The same rings true when using a makerspace in your classroom. You name it, it’s possible in a makerspace.

If you aren’t familiar with a makerspace, it is a place where students can create, problem solve, and collaborate. One of the greatest benefits of implementing a makerspace is that it shakes things up from your normal routine. It gives your students the chance to get silly and creative while giving you the gift of seeing your kids in a totally different light. Not only does it foster learning through inquiry, but it also helps to build overall classroom community.

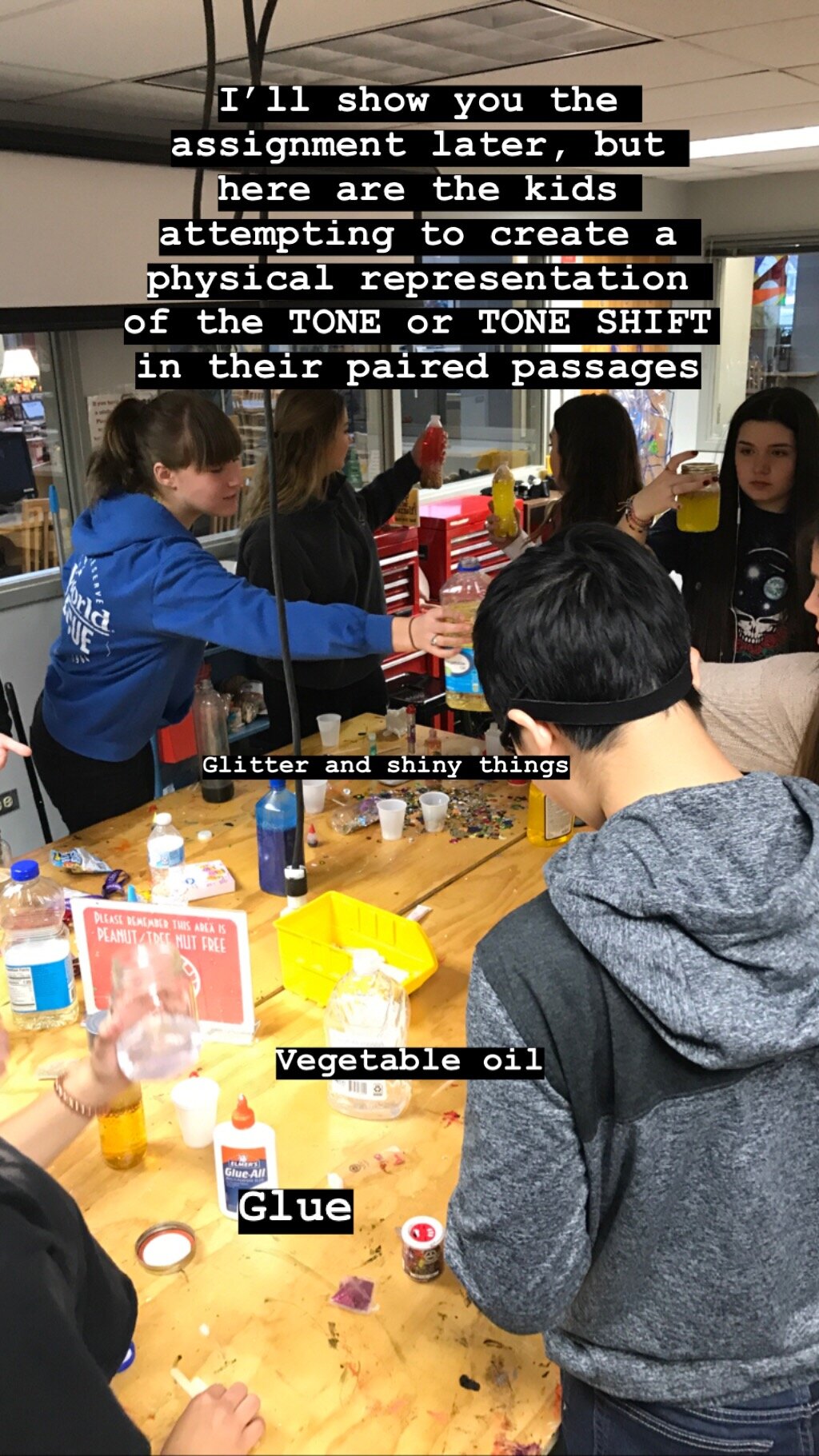

One of my favorite projects that I’ve done with my students was creating tone bottles to help them analyze the tone shifts in pre-selected passages from The Great Gatsby. The project itself is a bit silly, but the results were powerful in watching my students become more careful and close readers than they ever were before.

THE SPACE

Your makerspace doesn’t have to be organized in a meticulous or beautiful way. It should be full of odds and ends, most of which you probably have lying around your house. No matter what you include, your kids will find a way to use it! Consider:

Making your space mobile and shared. Find an abandoned cart and team up with a few other teachers to fill it with bits and bobs and slowly grow your supply stash over time.

This 3-tier rolling cart is awesome — I used it for a classroom library at school and now it’s a Makerspace cart for my toddlers at home!

Consider purchasing a green screen for anytime you want students to create something to film (reenacting a scene, a parody of a character, etc.)

Fabric scraps

Scrapbooking paper

Scissors

Hot glue and glue sticks

Things with glitter. And maybe some actual glitter. That’s up to you.

THE PROJECTS

The makerspace project that students create doesn’t need to be immediately rigorous, challenging, or even totally purposeful. Lean into the fun, frivolous, and silly for the project itself. We have the (good) tendency to want to make sure every single part of our instruction lines up neatly with skills and standards, but trust me, if you let go of the reins a bit in the “making” portion of this assignment, you’ll get a beautiful bang out of the analysis and reflection portion of the assignment.

WHAT TO MAKE?

A renactment of a scene using Legos (or headless Barbies, finger puppets, old socks, whatever)

An old-school diorama

A shoe box themed and filled to answer a question

A recreation of an important element of setting

A recreation of a motif or symbol

HOW TO ANALYZE?

What did you select in the creation of _________?

Why/how do these items accurately reflect ________?

How does this scene/symbol/object further contribute to your understanding of our Essential Question?

Given the limited supplies you had, why did you make x, y, and z choices?

Did you create your project based on your own interpretation (lens) of the text or did you attempt to recreate the author’s intention? Why?

THE GATSBY TONE BOTTLE

Valerie A. Person’s blog post inspired me to give this a shot in my AP Lang classroom. With her ideas in mind, I decided to challenge my students to select a passage from chapters 4 & 5 of The Great Gatsby and create a tone bottle that reflected the shift in tone from the beginning of the passage to the end of the passage. I then ALSO asked them to find a poem that had a similar tone or tone shift so that we could explore them as a pair.

It’s important to note that although this is a “makerspace project”, something that will involve obscene amounts of baby oil and glitter, the project begins and ends with textual analysis of TONE. I’m not trying to trick my kids here, but the reality is, we’re spending more time than they realize on the analysis part. Even the messy, maker part of the process is dependent on their initial analysis — they won’t even know what to put into the bottles if they haven’t analyzed (and reread and checked in with me!) the passage in the first place.

I’m happy to share my interpretation of this idea with you all. Here are a few pictures of how the project went, the sample I wrote for students, and a form to complete that will allow me to send over everything I have!

Mentor Sentences, Grammar, and Padlet: A Digital Lesson

Teaching grammar shouldn’t happen in isolation. Here is one Padlet-based lesson idea for teachers to practice grammatical concepts by writing and revising captions of various pictures.

I’m asked all the time, “How do you teach grammar?” “What workbook do you use to teach grammar?” and other variations of that question on a weekly basis. And my answer?

I DON’T.

This is not to say that I don’t teach the construction of language, the structures of punctuation, and how to proofread before submitting final work. I do all of these things. But what I haven’t done is assign a single grammar worksheet or taught any direct instruction lesson on a grammatical construct in a very, very long time.

The Grammar Teacher’s Danger Zone

There are two red flags to consider when planning for your grammar instruction: methodology and historical oppression.

First, as teachers embarking on any kind of grammar instruction, there are myriad ways to go about that instruction. Direct instruction through PowerPoint lecture, assigning work through a third party like NoRedInk, or teaching in context alongside other materials (rather than in isolation) are common considerations. Jenn Gonzalez from The Cult of Pedagogy explores research related to these options and shares clearly that grammar in isolation is not the way to go. Others here and here argue similarly. So if isolation (AKA a single Grammar Unit) is not the way to go, then let’s explore the power of teaching grammar in context.

The second danger zone that lurks in the background of the lessons we teach and the way we present grammar to students lies in the roots of oppression and colonization. In the United States, the English language was brought over from Europe and has remained the dominant language ever since. Native Americans have been long-time victims of the pressures of assimilation, especially when it comes to education. There have been mandated educational standards forcible enrollment in specially designed schools since the mid 1800s where “children were severely punished, both physically and psychologically, for using their own languages instead of English” (Klug, Cultural Survival). The message consistently sent by Standard English is that following the “proper” constructs of the language, one can be part of a more highly respected group of people. Cultural dialects and foreign languages have often been shelved at a lower place than Standard English, leaving us English teachers to sort this whole thing out as we look out at our sea of incredibly diverse voices in our classrooms. How do we teach English grammar in a way that helps students become stronger communicators and still validate the beauty and cultural importance of native languages and dialects? It’s not easy, but I can tell you right now we can stop doing two things:

circling every error we see with a red pen (or digital equivalent)

teaching full-length grammar lessons out of context

On a related note, you should hear what Vanessa has to say about teasing people about their accents:

So what DO we do?

I have a self-conscious disclaimer: this is one of my sore spots in teaching English. Grammar makes me very nervous and self-conscious, even though I mostly know what I’m doing. Honestly? I’m a terrible proof-reader. If you’ve been here on this website for any length of time, I can honestly report that I rarely do more than a quick skim to see if there are any glaring errors. If not? I publish. Readers catch mistakes all the time and I thank them, correct it, and move on.

I try to take this attitude with my students when we approach grammar instruction. Any time a grammar lesson is in play, it’s surrounded by encouragement to experiment and try. Not a single grammar lesson goes without a reminder that learning language is just another way to help my students find their voices. We learn constructs and play with them. Mostly, you’ll see grammar lessons in my classroom immediately following a major piece of writing as I teach the common errors in the context of the paper and making improvements. We also look at speaker’s and author’s syntax in writing, much like we look at diction and tone. You’ll hear me say things like: Hey! Do you see this? This is called an appositive phrase and this is where we see the speaker’s real attitude toward the subject come out! What would happen to this sentence if the appositive were taken out? That’s right! This would have been a pretty neutral sentence if it wasn’t for that side-comment appositive phrase. Let’s try manipulating that ourselves…

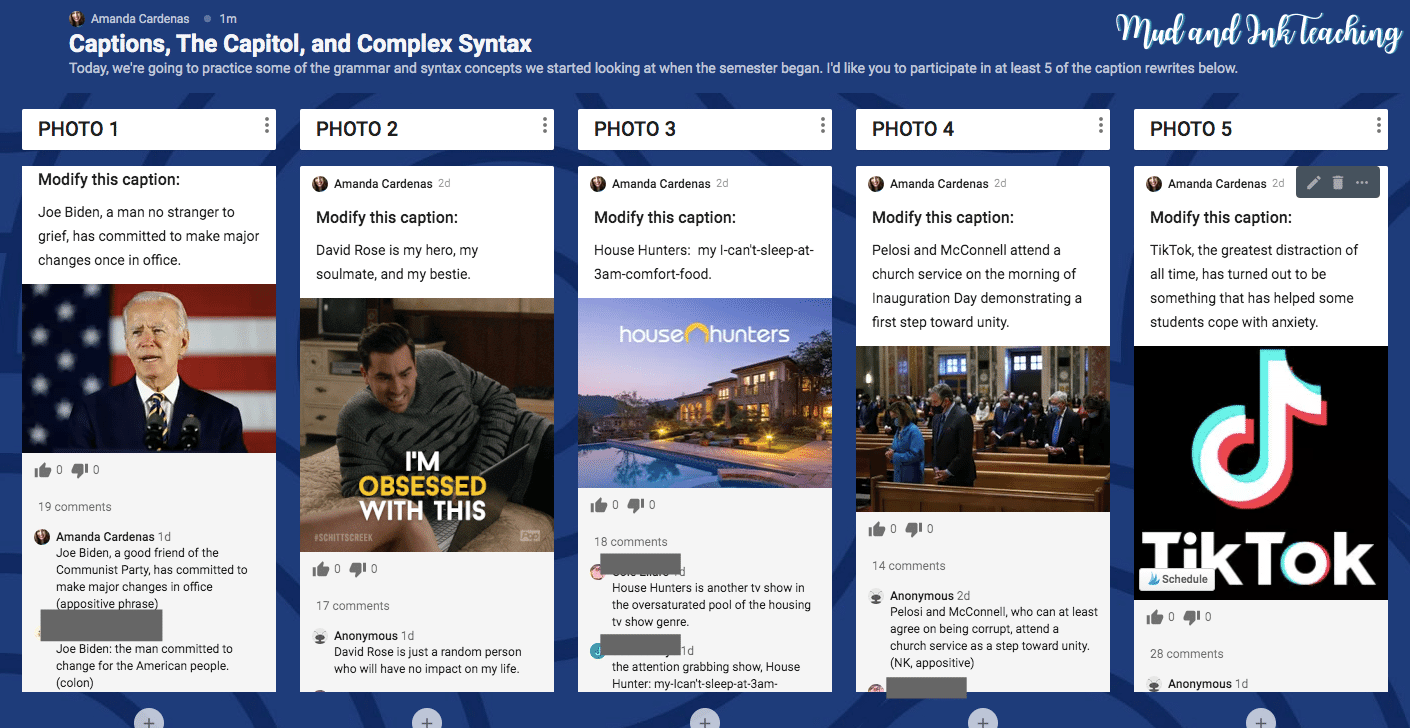

What does this look like with technology?

One lesson that I shared on social media recently is a caption writing activity that uses Padlet. Padlet’s software is free for three uses, and then moves to a paid tier. This activity is great because you can complete the activity, keep it live for a while, and then delete it — freeing you up to use Padlet again for another lesson.

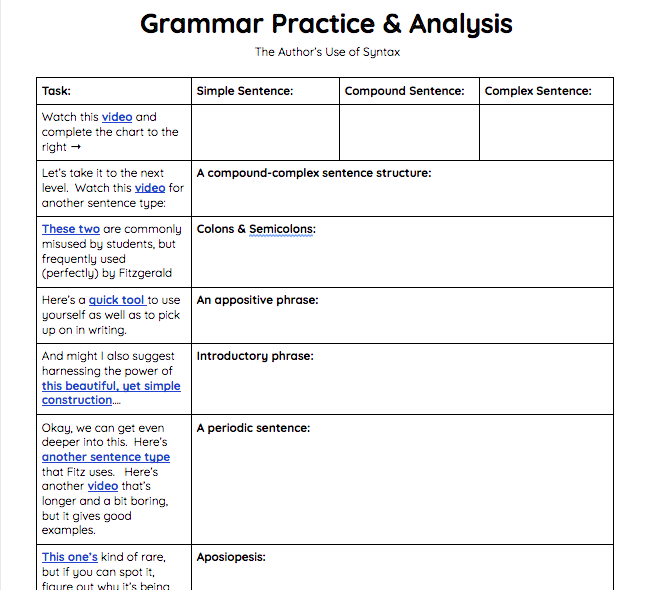

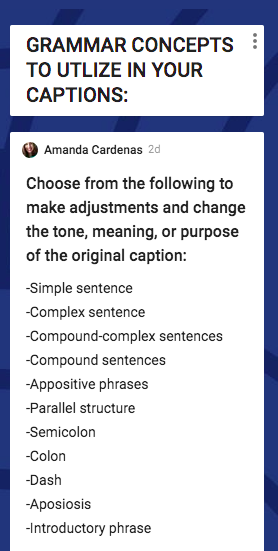

STEP ONE: CHOOSE AND TEACH THE GRAMMATICAL CONCEPTS

To do this, I built my students a YouTube playlist and sent them out to watch, take notes, and collect examples of 10 different grammatical concepts with varying levels of difficulty. About half of them were probably familiar to students from previous years of their education (this is a lesson I did with 11th grade) and the other half were probably new or generally unknown to them. My handout looks like this:

STEP TWO: PRACTICE AND PLAY

Once my students had a working knowledge of these concepts, we started looking at examples from literature and from of the major works we study for rhetorical analysis. We discussed Fitzgerald’s use of aposiopesis when he ends The Great Gatsby with the lines:

“Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther.… And then one fine morning—

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

We also looked at Elie Wiesel’s simple, yet powerful use of a semicolon at this point in his speech “The Perils of Indifference”:

“We are on the threshold of a new century, a new millennium. What will the legacy of this vanishing century be? How will it be remembered in the new millennium? Surely it will be judged, and judged severely, in both moral and metaphysical terms… So much violence; so much indifference.”

These discussions served two major teaching points for me: one, they put grammar into context, which as we know from the above research is imperative, and two, this is how I help students learn what analysis looks like. We can identify aposiopesis and a semicolon with relative ease, but the discussion about how and why are they effective given the context is where I want my students to be in their writing.

Now, it’s time to play. Enter: PADLET.

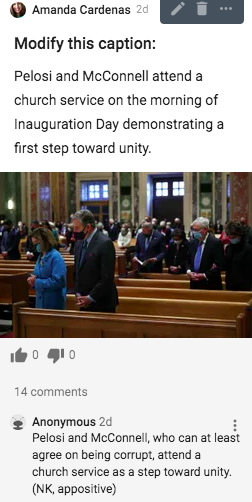

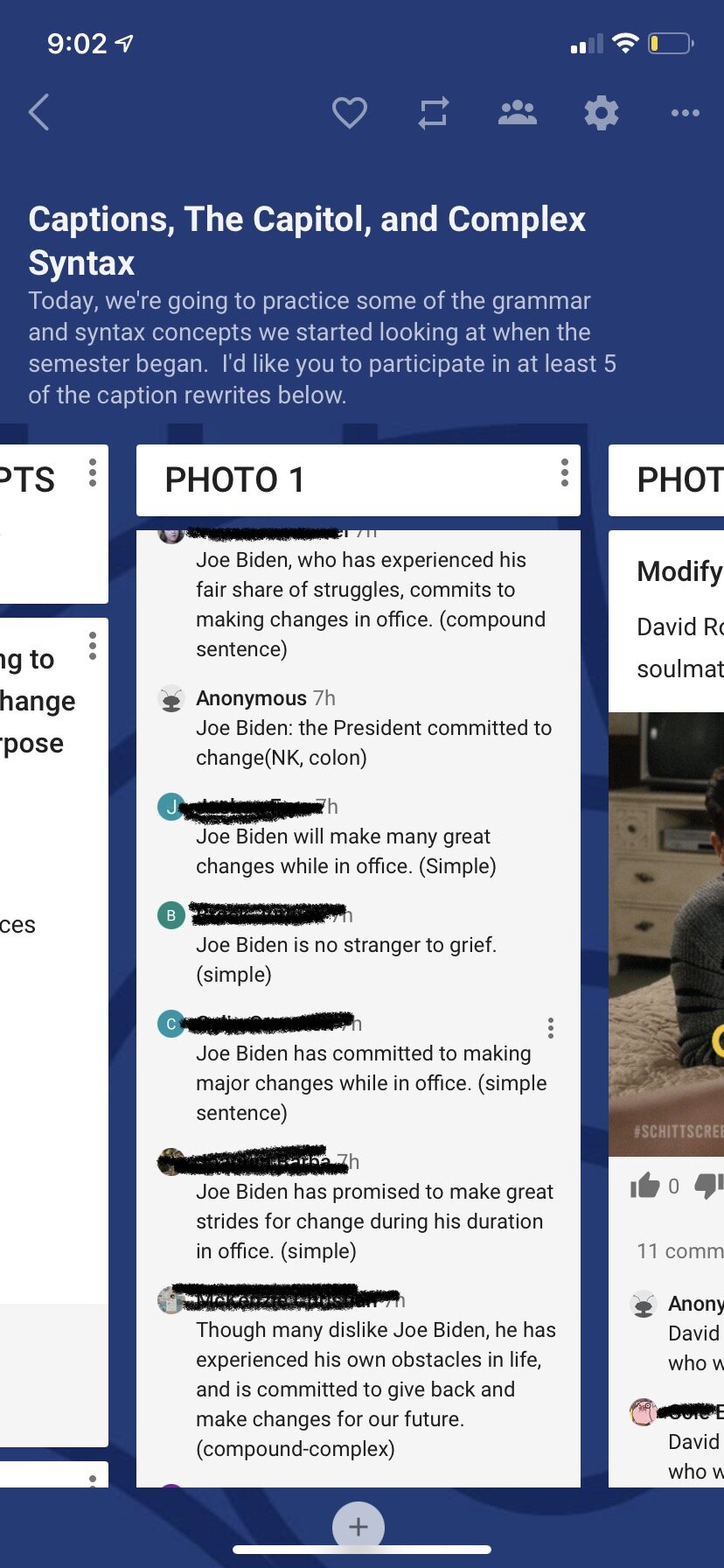

The idea behind this Padlet lesson is for students to manipulate language to create a noticeable change in meaning, tone, or purpose to a given sentence. Here’s how I set up the Padlet:

Head over to Padlet and login with your credentials. Click Make New Padlet.

Choose the SHELF option to set up the lesson the same way that I did. This option is what I use for any gallery walk type of lesson.

On Shelf 1, provide your instructions and any other notes for students to reference as they work.

On the remaining shelves, provide an image and a neutral-ish caption. For this particular sample, you’ll see a variety of images that are connected to what our class discussions have been about recently. The variety is key: choice in this lesson is critical so that students can find a comfort zone where they can experiment without feeling overly restricted.

Ask students to login to Padlet. This makes it easier to see who comments as it will automatically display their names.

Students now can see all of the images and captions and choose five (that’s what I asked for!) of them to modify using a grammar construct that we practiced earlier in the week.

That’s the gist! Afterwards, I had students read through the Padlet and upvote their favorite sentences, they pulled examples from the Padlet to analyze in small group breakout rooms, and, ultimately, complete a self-evaluation on their growth and progress in their ability to identify and analyze these concepts.

I’m curious to know: how have you been successful with grammar instruction in your classrooms? How else have you used Padlet’s shelf feature?

Let’s go shopping!

The Rhetoric of a Desperate Candlestick {Teaching an Introduction to Rhetoric}

A curse. A desperate staff of household appliances and fixtures. One dinner. How will rhetoric move the needle?

When it comes to introducing rhetoric, I used to always turn to commercials. Commercials have obvious elements to analyze and oftentimes very clearly lean toward an ethos, pathos, or logos approach, but the more I learn about the art of teaching rhetoric itself, the less I’m interested in having student slap labels on tools within an argument. What’s become more important to me over recent years and my training in AP Language and Composition, has been helping students understand the impact of the rhetorical situation — the BIG picture of the argument itself.

Have you ever introduced rhetoric, used a commercial, and at some point asked: who is the speaker? Who is the audience? Have the kids looked back at you with glazed eyes and vague answers like, “Um, Chester Cheeto? Us?” Advertising tends to be aimed at wider audiences, making the speaker/audience relationship difficult to analyze for beginning rhetoricians. Your kids might cry and learn what pathos is during a Budweiser Super Bowl ad with a lost puppy, but will they be able to tell you why on EARTH that was the angle that Budweiser took in the first place?